|

| Mark at work on one of the matte painted shots for the Sylvester Stallone picture DEMOLITION MAN (1993) |

Mark has long been a supporter of this blog and I've always enjoyed our conversations. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Mark for taking the quite considerable time in not only answering, correcting and expanding the 40 odd pages of questions, but also for tirelessly scanning and sharing with me hundreds of rare frames, clips and photos especially for NZPete.

Mark has long been a supporter of this blog and I've always enjoyed our conversations. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Mark for taking the quite considerable time in not only answering, correcting and expanding the 40 odd pages of questions, but also for tirelessly scanning and sharing with me hundreds of rare frames, clips and photos especially for NZPete. Thank you Mark... a Prince among motion picture magicians.

Restless At Night: A conversation

with Matte Painter and Visual Effects artist Mark Sullivan

--------------------------------------------

Q: Firstly

let me say just how thrilled I am to feature you on my blog, Matte Shot, and to

be able to have these conversations with you.

I’ve long been an admirer of your work in this field.

|

| Just out of frame may be a half buried Statue of Liberty... think about it. |

A: Thanks, Pete. I always enjoy your blog.

You dig up some great stuff.

Q: Thanks for that Mark. It’s always so heartening to get the ‘thumbs

up’ from industry professionals. So, let’s

start at the beginning.

Which part of the States do you hail from.

A: I grew up in Ohio, in the midwest. We

had long gloomy winters, so the sometimes unfriendly weather forced you to find

indoor hobbies.

Q: I

take it you’ve always had a lifelong interest in cinema as a viewer. What are the films, of the non-special effect variety are you fond of Mark.

A: That’s hard to answer, because there are

so many films, from so many eras that I like. In terms of a favorite

genre, I enjoy a lot of the hard boiled

crime dramas from the 1940s. A favorite

era are the early thirties pre-codes: THE WORLD GONE MAD, THE MIDNIGHT CLUB,

THE BLESSED EVENT, BED OF ROSES, CALL HER SAVAGE, BLONDE CRAZY, BABYFACE, NIGHT

NURSE, I AM A FUGITIVE FROM A CHAIN GANG, to mention a few. Most of my all time favorite actors seem to be

in 1930s movies. James Cagney, Myrna Loy, William Powell, Joan Blondell,

Barbara Stanwyck, Cary Grant, W.C. Fields, Paul Porcasi, and Edward G. It can’t

be nostalgia, I wasn’t alive way back when these movies were made.

Q: So you’d no doubt like things like

Cagney’s WHITE HEAT – one of my all time faves.

Of course THE THIN MAN is the perfect companion piece to many of the

films of the period too.

|

| Mark, circa 1982, armed to the hilt with sable brushes. |

A: Pictures like those two are just

masterpieces of casting. From the leads to the bit players.

Q: It’s

always so hard to pin down one’s all time favourites, as opinions change over

time and the odd film dismissed as just another film back in the day can sometimes

be dusted off much later as something of wonder. I did that just the other night with Costa

Gavras’ political masterpiece ‘Z’ and

the brilliant Richard Burton thriller THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM THE COLD – both

intelligent, gripping stories which left an indelible, potent impression upon me and stayed with me for

days afterward.

A: I can understand that. I go through phases of being preoccupied by

certain genres of movies. I have a

friend who is a collector of 16mm film prints. We’ve watched a lot of “heist”

movies: ARMORED CAR ROBBERY, GRAND SLAM, THE BURGLARS, THE MASTER TOUCH, THE

HOT ROCK, CRISS CROSS, GAMBIT. It’s fun

to anticipate the similarities, and the surprises of new twists that the film

makers have to come up with.

Q: I love heist flicks too. THE ITALIAN JOB and THE DAY THEY ROBBED THE

BANK OF ENGLAND are two terrific British heist shows and of course the

wonderful French thriller RIFIFI.

A: Yes!

LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN is another great one (not to be confused with a

similarly titled film from 2002).

Q: Of

course it’s true that many of the films we saw at a formative age – such as

PLANET OF THE APES, LIVE AND LET DIE, SEVEN DAYS IN MAY, TAKE THE MONEY AND

RUN, A DAY AT THE RACES, JOURNEY TO THE CENTRE OF THE EARTH, NETWORK and TORA

TORA TORA to name but a few of my faves, always remain fresh and as good today

on the twentieth viewing as I recall them as being when I was 12 or so.

A: I never tire of the 1940 THIEF OF

BAGDAD, IT’S A GIFT, THE THIRD MAN, GENTLEMAN JIM or KING KONG.

Q: We’re on the same wavelength there I

think Mark. I know it’s off topic, but

some of this old stuff you outlined is just still so satisfying. For me, so essential I just couldn’t imagine

life without the joyous insanity of The Marx Brothers, which no doubt says a

lot about the mindset of your interviewer!

A: I grew up loving those Marx Brothers

movies, too. A local art theatre would occasionally run them. That’s where I

first saw KING KONG, it was paired with the Marx Bro’s THE BIG STORE! That’s an odd, yet very entertaining and

pleasing double bill!

|

| "I was so excited by a Chesley Bonestell painting I saw somewhere, I tried to recreate it from memory in my eighth grade art class, using Prang Tempera paints". |

Q: I

always ask this question: what were the

films that made sufficient impact and lit that special effects curiosity in

you. For many in the effects business it

seems that KING KONG, 7th VOYAGE OF SINBAD and JASON AND THE

ARGONAUTS are titles which come up often.

A: I saw KING KONG and 2001: A SPACE

ODYSSEY at a young, impressionable age. Both of those films feature vast,

exotic, imaginary vistas. I think I

became equally fascinated with the settings as much as with the characters in

films, which may be a bit odd, but is probably appropriate for a matte artist

or art director or visual effects creator. I suppose it is all what my friend

Stew McKissick calls imprinting.

Certain films and images viewed at a certain age may help to form one’s psyche.

Q: Right on the money Mark. From our previous conversations over the past

few years it’s clear to me that you still value and hold deep appreciation of

the Golden Era of trick photography and the practitioners therein.

A: Some of that may be the imprinting thing

again. If you wanted to make your own movies, or experiment with your own

effects shots, it meant buying film, lumber, paint, glass, foam rubber and

aluminium, and learning how to use tools.

I was in my early thirties by the time the digital effects era seemed to

gel. I was formed by the world I grew up in.

|

| Mark painted this very Wagnerian influenced scene while at high school. |

Q: I

recall chatting with you years ago on the StopMotionAnimation

forums – back in the good old days when it was an essential fountain of

information on matte painting and other effects though they did some sort of

‘social network’ reboot of the site and scrapped all of those decade worth of

valuable old posts and hundreds of photos.

Such a waste.

A: I think it may have been beyond the

control of the fellow who maintains the site. But yes, there was quite a

collection of matte shot frames amassed there, mostly by you!

Q: Anyone

who reads my blogs will know that I am a huge supporter of the great pioneers

in trick work such as Frank Williams, John Fulton, Arnold Gillespie, Percy Day,

Jack Cosgrove, Willis O’Brien, Roy Seawright, Fred Sersen, Gordon Jennings,

Clarence Slifer and Norman Dawn. I never

cease to be thrilled to discover and learn more about the work these guys did

in advancing the medium, and I try to pay tribute as often as possible.

A: Yes, I hope you keep posting more

material on such pioneers.

Q: I

feel so fortunate in that through my blog I’ve been contacted by the family

members of many of these ‘giants’ who

accidentally stumble across this blog. I’ve had interesting conversations with John

Fulton’s daughter, Buddy Gillespie’s grandson Robert, who has been incredibly

generous; also family members of Wally Veevers, Les Bowie, Mario Larrinaga, Warren Newcombe, Irmin Roberts,

Fred Sersen and Gordon Jennings – all old school big players and some of whom

have interesting anecdotes, memories and in some cases, memorabilia which they

share with me occasionally with some most interesting material coming to light.

A: I’m looking forward from what you may

share from those contacts. I was amazed at all of those great test frames you

displayed of Jan Domela’s work, especially those shots from the 1930’s

Paramount features, which are so difficult to see nowadays.

|

| A series of sketches prepared for various student film ideas around 1981. |

Q: There is so much stuff that never made

it to DVD or even tape for that matter.

A: It seems that more and more little seen

films are getting onto DVD at last. But

those Paramount and non horror Universal pictures from the 1930s may be a

while.

Q: I

still find myself literally ‘gob smacked’ with so many of those classic effects

films and shots – the phenomenal smoky transformation and departure through the

jail bars in SON OF DRACULA is a John P. Fulton photochemical masterpiece and

to me has never been equalled, even with the digital realm. I’m

sure Universal’s long time visual effects cinematographer Ross Hoffman would

have had a lot to do with that.

A: Yes, I remember that one! That shot of Louise Allbritton

dematerializing into the floating vapours amazed me. How’d they ever get the

smoke lined up, and moving in such a perfect way, I’ll never know. Did they

have smoke trainers? I’d thought that

was probably one of the finest effect shots accomplished by Fulton’s team, at

that time at Universal. The Doctor Pretorious sequence, featuring the homunculi

in the bottles, in THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN is another Universal effects

department tour de force.

|

| Mark at work on a remarkably good Mario Larrinaga-esque New York skyline backing for his stop motion high school King Kong project in 1976. |

|

| The final shot, complete with an updated 70's Fay Wray damsel in distress. |

Q: How

about the astonishingly realistic burning of Chicago by Fred Sersen and Ralph

Hammeras in IN OLD CHICAGO and their equally thrilling deluge in THE RAINS CAME

– they’re still as good as it gets Mark, with staggeringly ambitious optical

work amid the excellent miniature destruction.

This stuff still holds me with a profound sense of “how the

hell did they do that?” even today – with very little of the

new age digitally manufactured stuff possessing that same sense of wonder.

A: You said it, Pete! I recall seeing a nice 35mm print of THE

RAINS CAME in the 1980’s at the Los Angeles County Art Museum. THE RAINS CAME

is a thesis on imaginative, dramatic and resourceful visual effects shot design

and application. Fearless!

Q: One

of my all time favourites in special effects and pure adrenalin has to be

THIRTY SECONDS OVER TOKYO with some of the very best miniature and matte work

committed to the screen. Have you seen

that show.

A: Oh sure!

I think I’ve seen some behind the scenes photos of the MGM effects crew

shooting the bomber POV shots. Huge miniatures!

Right out in the sunlight.

Q: I’d

be very interested in a rundown of some of the great old school effects shots

you’re particularly keen on.

A: I

always enjoy seeing a puzzler, one that you just can’t seem to break down and

reverse engineer. The shot of Tyrone

Power on his horse, leaping off of the bridge in MARK OF ZORRO is certainly one

of those. The zoom and dolly into the telephone booth on the lakeshore, as seen

from the boat deck in A LETTER TO THREE WIVES is interesting. Was the zoom built into the process plate as

shot on location, or was it a dolly shot with the camera pushing towards the

process screen on the stage floor at Fox?

You’ll sometimes see flawless travelling matte shots in pre 1933 movies,

before the common and widespread use of rear screen process shots. There is an amazing travelling matte of

Carole Lombard riding in a taxi, in VIRTUE, a 1931 Columbia photographed by

Joseph Walker. It doesn’t at all look

like a dupe, but as the shot goes on, you sometimes see a little transparency,

which is the only tiny giveaway.

|

| Hornet's Nest - an art school painting that Mark did in 1979. |

Q: Yep, Frank Capra’s THE MIRACLE WOMAN

made in 1931 had some great travelling matte shots with Barbara Stanwyck in a

burning church - maybe Dunning shots?

A: An

approach I really enjoy seeing sometimes is where the crew tries something very

audacious, perhaps beyond their resources. You can imagine someone saying, “This may not end up looking completely realistic, but it’ll be a

helluva shot, let’s do it anyway”. There are some startling scenes in THE

DAMBUSTERS that might be in this category.

The work in Howard Hughes’ HELL’S ANGELS was gutsy as, well, hell.

Q: Of course – HELL’S ANGELS. What an incredible film. The special effects work was Oscar material

in my book. Utterly superb miniature

cinematography, mechanical effects and composites by Roy Davidson and Cecil

Love.

A: I

recall seeing GREEN DOLPHIN STREET on television one night when I was a

teenager, and being blown away by some of the disaster sequences.

Q: Me too.

The MGM big screen RP shots were really impressive there. So crisp and

well balanced. Arnold Gillespie was a

genius at knowing where to blend the RP screen with the stage set, with some of

those shots having practical gags thrown into the shot in front of the process

screen. Terrific!

|

| In 1980 Mark embarked on an ambitious 16mm short film titled HIGHRISE, where a number of split screens, glass shots and miniatures were employed to imaginative effect. |

A: The

orphanage sequence in the 1949 MIGHTY JOE YOUNG always excites me. Now there’s

a sequence with almost every trick in the book: stop motion, matte paintings,

high speed miniatures, travelling mattes, back projection, static mattes, all

used in imaginative and exciting camera angles.

Q: Oh yeah.

I’d love to see a full breakdown or before and after reel on that

sequence. I have to gasp though where

that stuntman falls and actually breaks his ankle, right there on camera! Ouch!

A: Sometimes I’d rather not know of certain

things. It makes me a little uncomfortable seeing that shot, knowing the

stuntman was injured.

|

| A before and after tabletop set up from HIGHRISE. |

Q: Didn’t

you once tell me about that great camera move in SVENGALI – where the camera

pulls back from the ultra close up of the guy’s face, across the room, out the

window and carries on as a flight over the rooftops of a miniature city? I saw that one recently and it blew my

mind.

A: I might have, that’s another favorite

movie. There is a picture of Anton Grot working on this set up in a Kevin

Brownlow book. Looks as if the whole

thing is a forced perspective miniature built around the full scale window that

the camera dollies out of, from an extreme close up of John Barrymore. Grot’s

set designs in this one are astounding.

|

| A dramatic full matte painting also from HIGHRISE which is just the sort of shot I'd loved to have included in my recent 'Perspective Matte Shots' blog. |

Q: Being

a Warner Brothers show it’s really no surprise that such a fluid and high

concept illusion was pulled off so well.

That studio’s famed Stage 5 Camera Effects Department run by guys like

Fred Jackman and Byron Haskin really made a name for itself for a couple of

decades with jaw dropping effects shots – many of which I’ve elaborated upon on

this very blogsite. Stuff like YANKEE

DOODLE DANDY and PASSAGE TO

MARSEILLE still floor me with their eye popping trick

photography.

A: Yes, it seems like the WB effects stage

was really cranking up and doing matte shots at a fever pitch by the

1940’s. Pop in a DVD of one of those

Raoul Walsh directed Errol Flynn movies, like NORTHERN PURSUIT, or DESPERATE

JOURNEY, and you’ll see a heck of a lot of miniature and matte shots. I think there are even some shots in

DESPERATE JOURNEY with a sky matte painting being tracked to the plate, shot

with either a panning, or tracking camera.

Q: I’ve not seen NORTHERN PURSUIT and must

find it. DESPERATE JOURNEY had an

effects nomination I think.

A: I did not know that!

Q: Now,

was there ever a particular matte painted shot in any film that really sold you

on the process as a career.

A: Probably

the view of Kong’s grotto in the 1933 KING KONG. The effectiveness of that

environment is spellbinding. It is a supreme example of an almost impossible

dream like setting lucidly portrayed on film. Too bad KONG was made so long

after Gustave Dore passed away. I think he would’ve been impressed.

Q: Tell

us if you will Mark, a little about your background prior to entering the industry.

A: A very happy childhood, I think my

parents indulged me, but didn’t spoil me. Cats, dogs, ducks, hikes, bicycle

accidents and vacations. My main hobby

during grade school was building model trains, and collecting dinosaur

stuff. I saw the 1933 KING KONG (the

real one) when I was 12, and a year later I discovered Ray Harryhausen’s Film

Fantasy Scrapbook in a bookstore. Those events got me excited about movies.

Q: Art

has always been a strong part of your life I take it.

A: I think so, but sometimes not in a

conscious way. I grew up near a railroad and became fascinated by trains and I

enjoyed sketching them, but I was doing the sketches because I was interested

in the trains, more than producing a piece of art. I think it was the same way I got into

painting. I needed to create painted backgrounds for my Super 8 shots of clay

model dinosaurs. I was only interested

in making a background, and didn’t view the painting as a piece of art, really.

Q: Did you ever have any formal art

training?

A: There happened to be a pretty good art

school, right in my hometown.

I think the foundation

year program was very helpful. It consisted of color theory, two dimensional

design, art history, painting and figure drawing classes. But after three years

I felt the classes were becoming too focused on theory and offering fewer

practical things I thought could be useful for doing any kind of work

associated with the film industry. So at that point, it seemed like a good time

to move to Los Angeles.

Q: So

in your own non-film related art are you an Oil or Acrylic advocate. Do you have gallery shows of any of your

work.

A: I’ve always viewed acrylic as a way to

allow the painter to work a little faster - you don’t have to wait very long

for areas to dry before you can work over them.

I generally prefer the look of oil paintings, so if there is time I like

to use oils. I’ve been working on

various paintings over the years that I would like to display in a gallery at

some point.

|

| Matte art and stop motion figure from Mark's 1976 interpretation of KONG. |

Q: What

genre or school of painting do you follow in your personal art.

A: I enjoy so many varied types, themes and

genres of art, it’s hard to answer. But

if I had to point at some group, I ‘d pick the work of many illustrators from

the first half of the 20th century: N.C. Wyeth, Haddon Sundblom,

Gerome Rozen, Dean Cornwell, Maxfield Parrish, Fredric Gruger, Andrew Loomis,

Hugh Ferris. I love a lot of the Victorian and Symbolist painters, too: Arnold

Bocklin, Giovanni Segantini, Jean Leon Gerome, Sir Lawrence Alma Tadema.

Q: So

at what point did you first experiment with trick photography. Super 8mm I guess, as many of us tried to do

in the 70’s. Did you graduate to 16mm.

A: I saved up money from mowing yards in

my neighbourhood, and after a while I

had enough to buy an inexpensive Super 8 camera. The Kodachrome film was

beautiful. Paul Simon had it right. But I was unhappy with the poor results of

trying multiple exposures, so that led me to get a Bolex 16mm, a few years

later.

Q: Back

in the seventies we used to try and make in camera split screens and such in

Super 8 but the backwind was always a son of a bitch, with only so much footage

‘re-windable’ as I recall – and registration was a problem, especially with

early attempts where we didn’t even have a ‘through the lens’ viewfinder – so

it was all guess work! I recall early

attempts were even on single 8 – you

know, the 16mm roll that you’d flip over and shoot both sides and then they’d

split the roll at the lab and you’d get an 8mm developed film back – albeit one

with huge sprocket holes.

A: I have to laugh, this is all so familiar

sounding! Yes, I tried the Super 8

backwinding trick. You’d tape over the cassette core driver, so the camera

couldn’t wind the film properly, and later take the cartridge into a dark

closet or someplace, and push the length of film back into the feed chamber,

and then shoot the second exposure. The

registration of the two passes wasn’t good, they would really be swimming all

around.

Q: I

was amused to learn from a much earlier conversation with you a few years ago

that a book I had always found incredibly instrumental in getting me buzzing

with special photographic effects trickery was Jerome Abel’s The Making of Kubrick’s 2001 had a similar effect upon you as a fledgling

effects artist.

A: As I recall, the book itself isn’t too

specific as to how most of the visual effects were accomplished, but it was

intriguing to see what generally went into the making of that film. Since it

was one of the first “behind the scenes” pieces I’d ever read, it made me very

curious how other films were made, too.

Q: I

still leaf through that book from time to time and see it as way ahead of it’s

time – as was the film itself – in detailing the methods used. I was fascinated, though a little

disappointed in the Cinefex special on 2001 as too much time had lapsed since,

and too many of the key participants had passed away whereas Abel’s paperback had Doug Trumbull describe all of

the effects shots in an extensive photo section.

A: I guess that’s the great thing about

some modern films on DVDs. The documentation extras made during, or shortly

after a film’s production.

Q: A

group of us were blown away by EARTHQUAKE in 1974 and tried our own 8mm version

– the results of which were generally dismal but kept a bunch of teenagers busy

with models, split screens, floods and hair raisingly risky live ‘stunt fire

gags’ and home made pyro….Jeepers!!! As

usual with these amateur projects it was never finished. Does this sound familiar I wonder.

A: I didn’t get too far with the pyro stuff

for my Super 8 movies. A friend of mine

and I burned down a neighbor’s pine shrubbery after one of our pyro shots got

out of hand. My parents closely

monitored me after that episode.

Q: EARTHQUAKE

most definitely set me on a path of following matte artists and that realm of

sleight of hand, with Albert Whitlock without doubt being the master who’s work

I find simply astonishing.

A: I think it was THE HINDENBURG that got

me interested in how Al was using a lot of imaginative applications to his

work. The way the Hindenburg was made to emerge from the clouds was especially

interesting and dramatic.

|

| One of Mark's earliest professional matte assignments was to paint several mattes at David Stipes' effects house for a low budget show called WHAT WAIT'S BELOW around 1982. |

Q: Al’s

work on THE HINDENBURG was amazing, and it wasn’t until I spoke with Al’s

cameraman Bill Taylor a while back did I learn just how complex some of those

shots were – with the climactic explosion visual effect being something quite

extraordinary in concept and execution with multi plane matte art on moving

rigs and a series of cell painted direct overlays by Al frame by frame

animating the collapse of the airship’s envelope at the moment of

conflagration. Take a look at that shot,

it’s jaw dropping.

A: Dang!

Q: Speaking

of dirigibles, I think you told me recently that Disney’s ISLAND AT THE TOP OF

THE WORLD left an impression with

you at the time, effects wise and was a motivating factor toward

an effects career.

A: Well, after seeing KONG ’33, WHEN

DINOSAURS RULED THE EARTH, 2001, and MIGHTY JOE YOUNG in the late 1960’s to mid

1970’s, I was starved to see other adventure fantasy movies, taking place in

exotic lands. I enjoyed seeing ISLAND AT THE TOP OF THE WORLD enough, but it

wasn’t anywhere as startling and as formative as seeing KONG, for instance.

Q: Of

course Peter Ellenshaw would be an identity any budding matte painter would be

able to connect with – if not in person in inspiration and seemingly effortless

technique. Did you ever meet Peter.

|

| Final RP comp of the WHAT WAIT'S BELOW matte. |

A: No, I never met Peter. I recall catching DARBY O’GILL AND THE LITTLE

PEOPLE when it was re-released, sometime like 1975 or ’74. It made a huge impression.

Q: I’ve

said it before and I’ll say it again Mark, Disney’s DARBY O’GILL AND THE LITTLE

PEOPLE remains one of the absolute top visual effects showcases of all

time. There really hasn’t been a serious

competitor in the field of in camera perspective trick photography until Peter

Jackson’s LORD OF THE RINGS.

A: I absolutely love the perspective and

matte painting work in DARBY O’GILL. I

was always surprised with the appearance and direction of the death coach. It’s

almost shocking that the Disney people would put something that frightening

into one of their movies! I am glad they

did. It heightens the drama.

Q: DARBY

still delights and stuns me to this day with it’s seemless trick work. The fact that no Oscar was so much as

nominated here is criminal.

A: The Oscar process seems organic. A movie

just plain has to be popular, to get the popular vote. The bad deal was when

outstanding work, such as any number of Ray Harryhausen projects weren’t

suggested for nomination by the visual effects committee. Some other occurances

of fine work being slighted, to my mind, were CITY OF LOST CHILDREN, and the

recent version of CASINO ROYALE.

Q: I know the fx supervisor from the recent

Bond shows reads this blog so I’m sure Steve will be pleased at that

compliment. On Oscars, BLADERUNNER was another overlooked effects showcase in

my book, with sublime photographic effects work that always was complimentary to

the scenario and never oversold itself as modern films tend to do. I always felt Woody Allen’s masterpiece ZELIG

should have been considered as it’s as good a faux 20’s documentary you’ll ever

see. Staggering opticals by R/Greenberg

and cinematography by the great Gordon Willis at his very best.

A: ZELIG was such a fun idea, and well

executed, as you said. Excellent point about BLADE RUNNER. Visual effects in

modern films sometimes overstay their welcome.

A: No, I was in high school at that time,

in the midwest.

|

| Rocco Gioffre and Mark Sullivan, circa 1986 |

Q: Of

course your friend Rocco Gioffre managed to get on board under Matthew Yuricich

for Spielberg’s CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE 3rd KIND, and being a

natural talent, Rocco’s never looked back.

A: Yes, that was a great opportunity for

Rocco, and he obviously made the best of it.

He told me his first assignment, after arriving in Los Angeles, was

handing out candy at Matthew’s house to Halloween trick or treaters!

Q: Weren’t both Matthew and Rocco also from Ohio.

Sounds like a bit of a movie magician trafficking conspiracy to me.

A: Jim Danforth grew up in the Cleveland

area for a while, too!

Q: It

wasn’t long afterward of course when a number of future major matte painting

pro’s got their start such as Mike Pangrazio, Chris Evans and others.

A: The late seventies were the beginning of

a new visual effects boom.

Q: Tell

us how your first professional assignment came about.

A: My very first professional work was

creating some pre-production design art for a potential film project, that was

to be produced by a friend of Forry Ackerman, a man named Thad Swift. As you

know, Forry was a literary agent, and editor of the popular Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine, back in the 1960s and

70s. My friend Ted Bohus had visited

Forry, and showed him some slides of some of my amateur sci-fi paintings. As

per Ted’s suggestion, Forry was welcome to the idea of acting as my agent on

Thad’s project. Since I was still a

teenager in Ohio, without a car, my mom

volunteered to drive me out to Los Angeles, so I could work on the

project! That is some real parental

support. I did about 6 or 7 paintings

during July and August, 1979. They

weren’t my best because I may have been nervously trying too hard, but Forry

and Mr. Swift seemed fairly happy with them.

|

| Mark painted this wonderful Moon Colony conceptual canvas in 1980. |

Q: David

Stipes still has fond memories of the superb glass shots you painted for his

effects house David Stipes Productions for a low budget show called WHAT WAIT’S

BELOW, in fact he still has one or two of them in near pristine condition in

his garage which he very kindly showed me, albeit with one small scratch in the

paint, which is no mean feat with storage of delicate glass paintings I’m sure.

A: David Stipes and Ernie Farino were some

of the first guys I’d made contact with when I relocated to Los Angeles. They

were helpful and kind. My longtime friend Ted Rae and his wife graciously

allowed me to stay in their apartment until I found one of my own. Around that time, Ernie gave me some work for

a couple days helping him paint some animation cels for an effects assignment

he had. A couple years later, I got the

chance to work with David on the BELOW caverns project.

|

| Another glass painting painted by Mark for WHAT WAIT'S BELOW |

Q: Forgive me here, but the

first I’d heard the name Mark Sullivan myself was a small article about you in

a mid 80’s issue of Cinefantastique,

detailing your stop motion and matte art for the low budget film HOUSE 2, and I

was really so impressed.

A: Thank you Pete. HOUSE 2 was one of those

unique projects that I am fond of, more for the experience and opportunity than

the work I produced.

Q: You

seem torn between two poles Mark – that of being a stop motion animator and

that of a matte painter.

|

| Stop motion set up for HOUSE 2-THE SECOND STORY (1987) |

A It’s that darn KONG influence again.

I’d always been excited by stop motion, in particular the work of O’Brien,

Harryhausen, Jim Danforth, Randy Cook, Randal Dutra, Phil Tippett. The

convincing illusion of a living, breathing, sentient animal, or creature. There

is that fascinating “dead can dance” aspect to stop motion animation. You start

with inert materials: metal, clay, paint, foam rubber, and form them, then

animate them to suggest something living, as recorded on film.

|

| Combined stop motion brontosaurus action against painted backing, split screened with actors on a stage and flawlessly blended with matte art from the film HOUSE 2 - THE SECOND STORY |

|

| Again, animation and artwork all by Mark from the same film. |

Q: I

was honoured last year to be able to conduct an extensive and richly rewarding

interview and career piece on Jim Danforth – most definitely one of the great

all round talents of the traditional era effects world without question. So at

which point did you join forces with Jim Danforth.

A: I was lucky to be hired by Jim around

July of 1982. This was about a month after I moved (back) to Los Angeles, (the

work for Forry Ackerman in 1979 was just a summer job). I had called and visited some effects

facilities in the San Fernando Valley.

David Stipes was especially helpful and encouraging to me. David

suggested I call Jim, as he knew Jim had some matte work on the horizon for

Columbia television. I called Jim, and visited with him and his wife Karen,

later that afternoon. I brought along a 16mm projector, to run a short film I’d

made as an effects demo reel.

Q: I’m

sure my readers would be most interested in Jim’s influence on you as a

technician and the collaborative partnership you developed. What are some of the key things you learned

that would help you hone your craft.

|

| Mark's mentor and friend, Jim Danforth. |

A: I was enthused about getting to work

with Jim, and hearing his thoughts, opinions and advice on so many things.

There seemed to be two sides to the matte work we were doing. Of course, there

is a lot of technical knowledge that is required for putting these kinds of

effects shots together. I had only a limited knowledge of photography, so there

was I lot I needed to learn.

The second side of the work was much more

intangible, what might be called making artistic decisions. I might have been

painting a hue that may have been inappropriate near a horizon, or

inadvertently painting some patterns forming a tangent, or setting up a run off

composition. Jim would point out such things, and suggest corrections in a

clear, informative way. As we have seen, especially in the last thirty years,

technologies come and go, but if you can learn some artistic “picture making”

fundamentals, you can and will use them all of your life. Jim was insightful and helpful to me with

this difficult aspect of the work .

Q: Runs

us through the various projects if you will that you worked on for Effects

Associates, and any other outside work around this time.

A: The main, ongoing project was the BRING

‘EM BACK ALIVE television series. There were usually one or two shots per

episode. There was also some matte work on a made for television movie, a

western called SHADOW RIDERS. Jim created an ingenious split screen shot that

fused two locations into one, and there were two matte painting shots depicting

a schooner anchored off a coastline. Jim

painted one, and I the other. That was my first professional matte painting.

Another project at that time was a matte of a view of Manhattan for a Columbia

Mickey Spillane telefim. Jim shot the

plate down in Long Beach, and let me do the painting.

|

| Wonderful matte art for a minor made for tv movie, MURDER YOU, MURDER ME (1982) |

|

| ...and the final composite |

Q: I don’t think we ever had those shows

down here in NZ. BRING ‘EM BACK looks

great in terms of trick work from what Jim showed me, which I’d have none the

wiser of.

|

| BRING 'EM BACK ALIVE trick shot. Photo courtesy Jim Danforth. |

A: Well,

it wasn’t the most popular show in the states, either, it ran only one season.

I liked it, it reminded me of an old Republic serial. Some of my projects helping with the BRING

‘EM BACK shots weren’t just painting. I made some tiny stop motion parrots for

animation in front of a jungle painting, and there was a shot in a particular

episode that had to show Frank Buck jump a ravine on a motorcycle with a

sidecar, Evel Kneivel style. Jim was

creating a matte painting of a steep, rocky chasm. My part of the project was to do a tiny

painting of the motorcycle and stuntman onto cardboard. I cut the painting out, and made a paper doll

type of animation puppet out of it, even with some separate sections of the

motorcyclist wired from behind, so that

Jim could animate the body shifting to the changing angle of the bike as

it flew over the chasm. The little cardboard puppet-model was hung on tiny,

nearly invisible wires in front of the matte painting. The point of making the

painted cut out was to save time, and with painting it, it could be made to

closely match the motorcycle and rider seen in the surrounding cuts.

One amusing detail about Jim’s studio,

was that it was next door to an exotic bird importer. The effect of hearing the many birds squawkng

around three in the afternoon, which must have been their feeding time, helped

to put me in the mood when we were working on some of the jungle scenes.

|

| The final rear projection composite. |

About the

time work concluded on the television series, Jim took on a complex shot for

TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOTION PICTURE. The

shot basically represented a point of view angle as if the viewer were perched

on the wing of an airliner, descending through thinning clouds that reveal an

airport runway. Jim discusses this project, with some pictures, in your

interview with him, from May of 2012.

We worked on a couple matte shots for an

Andrew McLaglen directed film called SAHARA, not too long after the Twilight

Zone project. An exciting, ongoing project at that time was JONGOR, a film

project Jim wanted to launch, based on a popular pulp novel series from the

1930s. I painted a jungle, about eight feet wide, that was to have been used as

a backing for a stop motion miniature set up of an encounter between a giant

monitor lizard and an Arsinoitherium. Jim painted numerous, beautiful design

paintings, but things happened and I think he lost the option on the stories.

|

| Original matte art from the Brooke Shields adventure SAHARA (1983) |

|

| Composite of same. |

Q : From

what I gathered from my conversations with Jim Danforth, many of his mattes

were assembled as rear projected composites with quite a lot of success.

I’ve seen some RP matte comps on other shows which scream out ‘process’

with muddy colours, grain, hot spots and overall softness; so what made Jim’s

work so good.

A: Yes, Jim was very knowlegable and adept

at the process. He’d created many matte shots that one would assume were

original negative, because the color and clarity was so good. Something that was really fun about painting

onto glass, in front of a back projection screen is that you could thread up

the plate into the projector, put the glass painting in the matte stand, start

painting, then walk over near the camera, and see for yourself the illusion of

the painting placed over the film plate. Instant gratification!

|

| A gorgeous Hawaiian sunrise matte painting from a 1984 DODGE television commercial. |

Q: From

what I gathered from Jim it was common for the pair of you to paint on the same

matte shot. How difficult was that. Was

it a case of you doing your bit and then Jim having his input later, or were

you literally elbow to elbow.

A: Mostly the former. Sometimes I would come in on a Monday, and be

amazed at a painting Jim had created during the weekend. Like Al Whitlock, or Peter Ellenshaw, Jim

could work very fast. Sometimes I would

rough in a painting, and Jim would complete it, or sometimes I would go all out

on a shot, and Jim might make some changes, or refine an area where I might

have had some trouble with the perspective, or made some poor compositional

choices. We had to work fast on the television series shots. There might have

been instances where a completed shot for the Thursday night broadcast was

delivered on a Monday or Tuesday. Jim

worked hard on making the process projection plates. Sometimes he would create a built in contrast

mask, or sometimes the negative black and white contrast mask element would be

bi-packed in the process projector, with the positive projection print. The contrast masking would put information

into the highlights without adding density into the shadows, and blocking them

up. The end result of what was being projected onto the process screen, behind

the glass painting, looked almost like an interpositive, but without the orange

base. In terms of boosting shadow

information, Jim might have been using a slight flash. Of course, the masking and flashing work was

to preserve image information, so the duped image didn’t look contrasty. Many color filter and density tests were run

to achieve the perfect color balance.

The dupe plate test strip would be compared to a correctly timed

workprint on a lightbox. I think the

main reason Jim needed a hand with the paintings is that the optical work he

was doing with the plates was time consuming.

|

| An eight foot wide jungle painting for JONGOR, a film that Jim Danforth was trying to get rolling in 1983. |

Q: Many

matte studios would pass an individual painting among several artists. The Wally Veevers department at Shepperton

did this as did Albert and Syd at Universal and Illusion Arts. I think Yuricich said this occurred too at

Fox under Fred Sersen, though it got pretty damned competitive under Emil Kosa.

A: That was probably necessary when a lot

of work had to be done in a short time. Sometimes sharing the paintings can be

a good thing. If you are working with someone, or other people that have

ability, then I think two sets of eyes can be better than one.

Q: At

which point did you look at other means of compositing paintings, such as

latent image marry ups on original negative.

Jim seemed to use the method on a few shows though seemed to favour RP.

A: I had made a couple of in-camera latent

matte shots, experimenting with my Bolex 16mm camera when I was in school, so I

had a general awareness of the process. I learned a lot about the pertinent details

from Rocco Gioffre, when I was working with him at Dream Quest. Although Dream Quest had an accomplished

optical department that could help with dupe matte shots, Rocco usually

preferred the in-camera, latent image original negative approach. The picture quality looked perfect because

nothing in the composite image was duped, and there was an attractive, “get in

and get out” aspect to the technique. You are simply careful about notching the

edge of the camera negative during plate photography, which allows you to identify

your separate takes and test footage using rewinds, back in the darkroom of the

effects studio. For instance, three edge

notches might mean take three, four notches are take four, and so on. Once you

load the film up into the matte painting photography camera in the correct

perforation order, you are good to go. No need to spend time or money creating

a dupe film element to comp with.

|

| A beautifully atmospheric night matte painting that Mark made for another DODGE tv commercial in 1986 involving a junkyard dog. |

|

| The final composite. |

Q: So, how difficult would original neg

mattes have been on the old Technicolor 3-strip process such as for the amazing

Cosgrove shots on GONE WITH THE WIND.

A: From what I’ve read, difficult. I think

there may have been an article by Clarence Slifer for American Cinematographer,

describing the various problems. I believe many of the matte shots for an

earlier Selznick production, THE GARDEN OF ALLAH, were handled as in situ glass paintings to avoid the difficulties with

having to use a Technicolor camera and the three negatives for re-exposure in

the matte department.

|

| The New York city rooftop zoo matte painting from Madonna's WHO'S THAT GIRL (1987) |

|

| The composited shot with colourful parrot matted in flying through the scene. |

Q: Ever

resort to bi-pack or YCM separations to achieve comps.

A: Yes.

I recall Rocco using high gamma (low contrast) YCM, aka RGB seps on

projects frequently at Dream Quest, and sometimes simply bi-packing a

registered color print ( a print made on Bell and Howell perforations) for

something like some background street traffic in a night shot, or some birds in

a sky, for instance. Our pal Bob Bailey worked a lot with Rocco and I on the

optical elements we used at Dream Quest.

When I was at ILM, if it was decided that a matte shot had to be done

with duping the live action, often I would ask to have RGB seps made in the

optical department, exposed onto color negative with a built in matte, and held

as latents. The matte may have been

created as a film element from artwork, or created on the optical printer head

with taping on bits of opaque plastic. We would then load those latents up in

the matte painting camera. That way, we could use soft edge blends where

needed, and it would save the painting from being duped.

Q: Did you ever find yourself in a position

where the effects provider mandated that seemingly cumbersome and headache

inducing method – I think it’s known as the interpositive filmstock method -

which Slifer and Yuricich tended to stick with at MGM where colours must be deliberately

painted in bizarre hues to work. Doug

Trumbull was a big advocate, as was Matt’s brother Richard apparently.

A: Yes, we used the 5243 interpositive

stock for a project at ILM, once. The matte paintings were depicting a volcano.

The stock was great for emphasizing something that had to be light emitting,

and glowing, such as the volcanic magma. It was later decided by others to use

the paintings for straight optical comps, so some of them ended up looking a

bit flat in the final comps.

Q: At

which point then did you collaborate with Rocco Gioffre.

A: The California visual effects industry

was still small in the early to mid 1980s. I got the sense that almost everyone

knew each other. Rocco knew Jim Danforth, and I met him when he paid a visit to

Jim’s shop once. About the time I finished the work with David Stipes, I got a

call from Rocco to work at Dream Quest, to help with BUCKAROO BANZAI and some

television projects.

Q: Rocco

is one heck of an effects artist in my book, and I find his work really

something else. I’m delighted to be

the owner of two of Rocco’s traditional painted mattes which bring me no end of

joy, alongside my pair of old Newcombe mattes from MGM.

A: Rocco is enormously creative. He was

always coming up with inventive camera techniques, and was adept at using

effects to augment the paintings, -miniatures, animated and rotoscoped birds,

water elements, high speed photography for rain and ocean waves, etc. He’s the goods, alright!

|

| Mitchell matte camera on heavy steel pedestal with HOUSE 2 matte art. |

Q: I

loved the shots you and Rocco did for Madonna’s wacky WHO’S THAT GIRL? with that ingenious and complex multi plane

trick shot for the car hanging off the building. Brought back memories of the old school John

Fulton or Warner’s Stage 5

type gags of the 40’s,

and is just so brilliantly

executed with matte art, miniatures, stop motion and foreground art all in

one. Bravo.

A: Thanks, Pete. That particular shot was

a fusion of three things I love: matte paintings, miniatures and stop motion

animation. On top of that, I had the pleasure of working with some friends on

it. Bob Bailey contributed to the photography, Henry Darnell built the

excellent car model, and Rocco helped with setting up the miniature.

Q: I

never tire of studying those shot breakdown photos for that one. To my mind this is what movie magic is all

about.

A: I find it is almost more fun sometimes

seeing, and learning how something was done, than enjoying the end result in

the movie.

Q: Dream

Quest Images was one of the top effects providers from the early 80’s and

showed no end of creativity and artistic ability. My all time

favourite article in Don Shay’s Cinefex is the one all about Dream Quest,

published around 1984 or so. Were

you a Dream Quest employee at that time.

A: It was fairly modest facility when I

started, in January 1984, maybe a year or so after the magazine you are

referring to. There were maybe 16 to 18 people there.

Q: I

have the utmost respect for Dream Quest as an outstanding visual effects

house. I would go out of my way to see

shows they had worked on and was consistently blown away. It was so sad to see Disney wreck a once

proud and vital trick shot operation.

A: I enjoyed being there, working with Rocco

and Hoyt and the gang, for a while in the 1980s. I’ve no idea why Disney would have closed it

down.

Q: I

think Rocco once told me that you painted the movie theatre interior shot for

Joe Dante’s GREMLINS. Did you help out

on any of the other mattes on that show.

A: No, just the background wall for a

shot of the Gremlins inside a movie theatre. Rocco had completed a couple

shots, but that was 2 or 3 months before I started.

A: No, just the background wall for a

shot of the Gremlins inside a movie theatre. Rocco had completed a couple

shots, but that was 2 or 3 months before I started.

Q: Although it wasn’t as good a film as I’d

have hoped, I absolutely loved the effects work in Paul Verhoeven’s

ROBOCOP through and through. Not many

people know that you painted mattes on that film, once again with Rocco, though you never received a screen

credit.

A: It was just a couple shots, a down angle

of a skyscraper, and a sunset shot of the skyscraper where most of the story

took place. I don’t remember if the sunset shot made it in to the final

cut. I don’t think you can always expect

a screen credit, especially if you’ve only worked on one shot.

|

| Close up view of Mark's magnificent ROBOCOP climactic painting. Boy, do I love this one!!! |

Q: The final down view matte is sensational

Mark. Incredibly detailed painting for

such a brief shot. I don’t recall ever

seeing the sunset shot.

All of the effects from the stop motion to the painted mattes were

terrific on that picture and it should have been up for Oscar consideration in

the effects stakes I feel… but don’t get me started on bloody Oscar injustices.

A: The effects were well used in that

movie. They were used economically, just enough for some thrills and to tell

the story.

Q: You

were fortunate to have met several of the real old timers such as Matthew

Yuricich, Albert Whitlock and I think maybe Lee LeBlanc too. What of those meetings remains fresh in your

mind.

A: Matthew was a natural raconteur. Some of his stories about working at Fox and

MGM in the 1950s were hilarious. Of

course, many of those stories are in your post about Matt, from last year. Albert Whitlock impressed me as being

something of a philosopher. When some

friends and I were visiting Illusion Arts once, Bill Taylor was running some

test shots on a Moviola for us, and Al was watching. Bill had shot a white card

against black, and used the film negative as a shadow element. I think I

blurted out “Wow, what a good idea”. I recall Al

saying, “Yes, that ‘s what it’s all about, isn’t it? The good idea”. Unfortunately, I

never met Lee LeBlanc. I once had a

chance to talk to Linwood Dunn. It was a huge thrill meeting someone who had

worked on KING KONG and CITZEN KANE, among other classics. I had a lot of

things to ask him about O’Brien and KONG, naturally.

Q: Did

you get to watch a veteran such as Matthew at work.

A: No, not Matthew. I did get to watch Jim

Danforth work on some paintings. I once visited Illusion Arts when Albert Whitlock was working there, and I watched over his shoulder briefly. I happened

to visit Jim’s studio when he was in the midst of his work on NEVERENDING

STORY, and saw many of those excellent shots in various stages of completion.

|

| Inside Mark's matte and effects studio. |

Q: Jim’s NES glass paintings were

spectacular indeed. Jim’s matte of the

crystal valley is phenomenal.

Did you ever get to visit Albert’s department at Universal.

A: Yes!

Syd Dutton very generously took off part of an afternoon and showed both

Rocco and me around the matte department at Universal. This was probably less

than a year before Universal closed it, so I am very thankful to Syd. It was

exciting and inspiring seeing the paintings used in the Hitchcock movies as

well as THE HINDENBURG, THE STING, GREYSTOKE and the stunning work Syd had

created for DUNE.

|

| Original negative matte before and after from MIRACLES (1985) |

Q: I

got to see some of Al’s paintings at Universal in the late 70’s when the Studio

Tour stopped at a special effects stage.

Among the various mechanical effects and gags on display they had Al’s

glass paintings, one each from EARTHQUAKE, THE STING, AIRPORT 77 set up with

some other stuff.

A: I can recall taking that tour at some

point too, and seeing some of Al’s work.

It’s great that Universal appreciated him.

Q: I still remember the rather spunky tour

guide telling us all about Albert and the magical scenes he created as she

showed us the mattes. I think they had

35mm RP display of the final comps too next to the paintings as well for

memory. Speaking of Albert I remember another show that you

painted on, with Al’s son Mark. PREDATOR

II wasn’t a bad show by any means as far as sequels go and it’s interesting

that a trio of artists painted the mattes on that – Mark Whitlock on moody

night skies and such, Rocco on skyscrapers and cityscape plus yourself

supplying the alien spacecraft. Could

you tell us about that project.

A: Rocco asked me to help him get some of

the shots done, so I took on the shot of the alien craft, that had somehow

parked itself in an abandoned subway tunnel.

Q: Yeah… I never quite figured that one

out. A bit like Wilford Brimley building

a functional alien spaceship out of chopper, snowplough and VCR parts in Carpenter’s

THE THING… kind of wacky!

A: The

production designer loaned us some parts of the Predator costume, and told us

the use some of the shapes and stylings in the design of the spacecraft.

Q: Did Mark Whitlock paint at your

facility.

A: No, I think Mark had a matte painting

set up in his home garage.

|

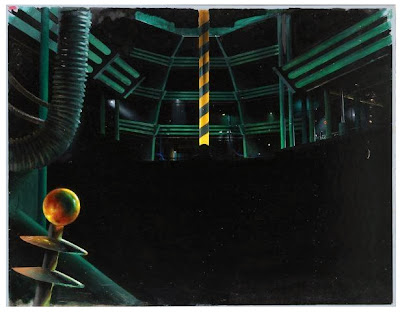

| The alien predator spacecraft in a subway tunnel (!) from PREDATOR 2 (1990). |

Q: Tell

us about ISHTAR. Not the best box office

opening weekend of 1986.

A: Poor ol’, ISHTAR. It was okay,

certainly not on par with most movies that Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman

usually appear in, but not as bad as it’s cracked up to be. At least that’s how

I remember it.

|

| One of several unused mattes painted for ISHTAR (1986) |

Q: I’ve

got a great photo of a vast matte you completed for ISHTAR but the scene was

dropped prior to it being filmed. How

did that sit with you.

A: I felt some disappointment when most of

the matte work was cut out or put on hold. But, the experience of going over to Morocco,

to consult with the crew, and making the hold out mattes for latent matte shots

was tremendously exciting and educational. The second unit director on some of the matte

shots was Mickey Moore, who lived an amazing career in the film business. He

started out in the 1920s, as a child actor portraying the apostle Mark in Cecil

B. Demille’s KING OF KINGS.

|

| ISHTAR matte painting of a mosque. |

|

| Exterior plate with masking for matte. |

|

| The final composite. |

|

| The live action plate, carefully masked off to preserve the image of the Emir so as to avoid having to repaint him back in with the rest of the matte top up that's required. |

|

| The finished ISHTAR comp of the above that I think never made the final cut. Mark told me that an entire subplot was omitted at the last minute, with some mattes becoming casualties. |

Q: So,

where did ILM fit into your career timeline Mark.

A: Around early fall of 1988, I received a

call from Scott Ross, ILM’s general manager. Except for some of the camera

people, most of the matte department personnel had departed ILM that summer,

for various reasons. I think it may have been one of those things where each

person had his or her own reason for moving on to something else, but the fact

that all were leaving at the same time probably cast an ominous tone that

really wasn’t there. ILM had INDIANA JONES AND THE LAST CRUSADE, THE ABYSS, and

GHOSTBUSTERS 2 in house, and all of those projects each had various matte

painting shots in need of completion before Memorial Day weekend of 1989.

|

| One of the numerous mattes Mark painted during his ILM tenure, with this being an invisible matte extension from BACKDRAFT (1991) |

|

| Final BACKDRAFT comp with painting, miniature roof with pyro and fleeing actor doubled into rooftop inferno. |

Q: I

believe you headed up the matte department, so I assume guys like Michael

Pangrazio and Chistopher Evans had long since moved on. Who were your fellow painters in the

department at that time.

A: Yes, Michael had joined Craig Barron to

start Matte World , and Chris continued working with them, and also came back,

at times to work at ILM, on various matte projects. Early on, for about 4 or 6 weeks, I was the

only painter in the matte department. I

had suggested to the powers that be that they consider hiring Yusei Uesugi, who

had done some nice work assisting both Rocco Gioffre and me at our shared

studio space in West L.A the previous year. Rocco had met Yusei at the Tokyo

International film festival, in 1985, when Rocco had appeared there as a

speaker. Yusei was a student at the

time, residing in Tokyo, and approached Rocco with some samples of his matte

painting experiments.

|

| One of Mark's conceptual paintings for a key matte for INDIANA JONES AND THE LAST CRUSADE (1989) |

|

| The actual matte painting as seen in the film. Just love that diffused backlight and 'density' |

|

| Artist Yusei Uesugi at work on 'leap of faith' matte painting. |

Yusei started at

ILM around late January of 1989, as I recall, and we were quite fortunate to

have Caroleen Green (now known as Jett Green) join us for several months. Paul Huston was another huge talent who

seemed to enjoy working with the matte department. We were able to save some

time on certain shots by using some of Paul’s beautiful miniature work, in lieu

of painting everything in the frame.

For

instance, several of the shots in the INDY 3 “leap of faith” sequence were

entirely Paul’s work. Paul carved and shaped the steep cliff walls, and also

modeled and painted the trompe l’oeil

bridge piece that Indiana Jones steps onto, in that sequence.

|

| Another angle from the same set piece with painted cliff face. |

|

| Mark, shown here busy with another INDIANA JONES painting - the result of which may be seen below. |

|

| The finished comp of above painting. |

Q: How

about cameramen in the matte department.

A: Wade Childress, Bob Hill, Jo Carson and

the multi-talented Harry Walton were our main camera people on projects at that

time. I think it may be obvious, but the

matte painting process really involves an enormous amount of communication and

joined thinking between the matte artist and the matte camera person. For instance, I worked with Harry on a pretty

challenging matte shot for THE ABYSS, a movie that Dennis Muren was

supervising. A portion of the shot was

an original negative plate, another portion was a rear projected (behind the

glass painting) element of a large, live action wave, and there was a

foreground element of some sailors that was an in camera travelling matte. Optical had prepared a black and white hold

out matte that Harry would bi-pack when he was shooting the painting with the

projected water footage onto the latent image roll. Harry would then have to load up the latent

onto his optical printer and expose in the positive RGB separations onto the

take. With all of the colors and densities that had to be matched and balanced

for all of the elements, it was a lot to keep track of.

|

| Complex matte effects shot from James Cameron's THE ABYSS (1989) |

Q: Describe

for us if you will the ILM matte painting department set up.

A: I will try to give an overview, at least

generally from around the time I was there, way back when. In terms of the

staff, there were usually about two to four painters employed, and three camera

people, and usually two camera assistants.

We could bring in help from other departments as needed: model builders

for reference miniatures and miniature elements, grips and electricians for

special rigging set ups, and of course the optical department to create RGB

separations, registered color prints or projection plates. The budgeting

process was a matter of the department head submitting time estimates on shots

that were in consideration of being submitted to the department. Those considered shots were usually

accompanied with storyboards or sketches from either the ILM art department, or

the client. Sometimes the matte department would be involved with creating

concept art sketches in the shot design phase.

In terms of the physical infrastructure, there was a very pleasant

second story painting area studio, with skylights over each easel. The paintings would be lowered to the first

story photography stage down a little dumbwaiter elevator system. The matte

photography stage had a small, light-tight film changing room, for loading and

unloading camera magazines, and a set of rewinds for breaking down latent image

rolls. There were four permanent camera set ups with matte stands, one was a

versatile system with both the camera, two painting supports and a process

projector mounted to a motion control rig.

There was a front projection matte stand that we never used, and two

fixed matte stands, constructed from box steel, for locked off shots. One was a Bell and Howell 2709 four-perf camera mounted to a steel pedestal, and the other

with a Vista Vision eight-perf

camera also mounted on a steel pedestal.

All of the stands and pedestals were bolted to the floor, which I

believe was poured concrete under the linoleum. The Vista-Vision set up was

used to photograph paintings that were intended to be comped as dupes in the

optical department. The eight-perf stand

had a backlighting arrangement, which would allow for a front light light, back

light pass, so a painting could generate its own matte (We later found that

technique to be troublesome - a much softer, separately generated matte could

hide matte lines better). Shooting onto

eight-perf would give the optical people more negative to work with, for better

resolution and less grain.

|

| A striking sense of lyrical romanticism in this matte shot from Akira Kurosawa's DREAMS (1990) |

Of course,

the ILM matte department was well established and organized long before I got

there, by folks like Harrison Ellenshaw, Neil Krepela, Craig Barron, Michael

Pangrazio, Michael MacKenzie, Wade Childress and other ILM people I am probably

unaware of. My only involvement with something new in terms of the physical

plant was some design input into an updated, entirely motorized matte stand set

up that was begun around the end of HOOK, but never completed because of the

burgeoning digital technology.

|

| Mark's original painting hanging on the walls at ILM years later. |

A matte artist could retain a little more creative control by being involved in the compositing, and completing a matte shot inside the matte department. Nothing against the abilities of the optical department people, they were great. But there was less artistic satisfaction, as it was usually disappointing to see how the painting would look from being duped. Certain colors and densities could be lost, important tones that gave the painting its subtlety and realism. I always thought of the phrase “lost in translation”. I think what the ILM management mostly wanted was a streamlined process that was predictable and easy to budget: paint the painting, shoot it, and send it to the optical department. End of story. It’s understandable in the sense of desiring a fairly predictable and reliable working routine. I got the reputation of being a little persnickety, for sometimes overstressing that the matte shots should not go through optical. Twenty five years later, considering the speed and quality potential of digital compositing, controversies surrounding film comping issues of that time may seem silly and trivial, but that was the only way to do things back then.

|

| Another of Mark's mattes still on the ILM hallway walls. |

Q: I guess it goes without saying that for

the artist to have overall ownership of the process right from word go to final

composite was pretty much unheard of by this time. Guys like Albert Whitlock must have been a

rare commodity indeed where complete control of the shot and each and every element

were fundamental.

A: Every film project and every studio has

its own persona, and way of doing things. I get the impression Percy Day might

have retained a good deal of control over his work.

|

| Steven Spielberg's tiresome fantasy HOOK would gain Mark an Academy Award nomination for his paintings and supervision of all matte work. |

|

| One of my all time favourite matte paintings, and from one of my all time least favourite movies. |

Q: I

take it Craig Barron had moved on by then to start up his own company Matte

World, a boutique effects house specialising principally in painted mattes that

would certainly make it’s mark in the industry with many memorable shows.

A: Yes, Craig, Mike and the Matte World

people did some fabulous work. One of the things I really enjoyed about being

at ILM was seeing many of their old matte paintings hung up in the halls and

offices.

Q: I

guess it would have been HOOK as something of an artistic highpoint for you at

ILM – despite the film being typically schmaltzy Spielberg (is there any other

kind?)

A: In answer to the second part of your

question, some of Spielberg’s films are among my favorites, JAWS, RAIDERS OF

THE LOST ARK, LINCOLN. I wouldn’t say

the schmaltz is always typical. I don’t consider HOOK as any artistic

highpoint, but it was an enjoyable project to work on. Well funded, a nice crew of talented people

to work with, and an opportunity to create some imaginative landscape vistas.

Q: Gorgeous

mattes and worthy of that Oscar nomination – though great effects do not mean a

great film by any stretch.

A: A great “effects movie” is a rare bird

indeed.

Q: Personally

I’d regard that epic glass painting of Dana’s apartment building for

GHOSTBUSTERS II as being not just your best, but one of the best matte

paintings ever!! Magnificent perspective

and mood.

A: You are very generous! I was excited by

the design of that shot, and spent a little extra time on it, and did the whole

thing in oils.

|

| The final shot featuring Mark's vast painting, live action street action and an optical ghostly nanny figure. |

|

| The final composite, model, glass painting and live action. |

Q: Sadly

that beautiful piece met an unfortunate fate, didn’t it.

A: Yes, at some point when it was being hung

up to display, it was dropped and it shattered. That’s the sad and sometimes

dangerous thing about using glass. I would use a heat lamp to dry the oil

painted glass paintings overnight. Once I stupidly aimed the heat lamp at only

one end of the painting, where I’d been painting, and by the next morning, the

temperature difference between the ends had cracked the glass.

Q: Was that painting salvageable.

A: Yes, Paul Huston helped me to epoxy

the backside of the painting, it was the castle shot for INDY 3.

Q: I’m

sure there are more than a few glass shot mishaps over the years. I know a key matte used in

Powell-Pressburger’s THE RED SHOES cracked during photography under the hot lights needed for the slow

Technicolor film stock, and I heard from Matt Yuricich of numerous ‘crack ups’

with even his famous YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN castle glass painting requiring a patch

up prior to filming after someone stepped on it.

A: I had heard that once one of Matthew’s

paintings, being photographed onto the very slow interpositive stock, with a

huge array of lights, actually caught on fire!

|

| The original matte art from the opening shot from Oliver Stone's THE DOORS (1990) |

|

| A closer view of the colour and texture of Mark's artwork which would, in the final film, be timed to a sepia look. |

|

| The end result, and a good example of an invisible matte shot. |

Q: So, how long did you stay at ILM, and where did you work next.

A: During some of my time at ILM, I lived

in Berkeley, across the bay. I had a small studio building on the lot behind my

home, with film equipment. Kind of my own mini matte department. Occasionally,

I would get a call to do a small project, and I enjoyed working in my home

studio. I never intended to permanently leave ILM. I got caught up with working

on smaller freelance projects on my own, and never found an opportunity to

return, at least on a full time basis.

|

| Hundreds of wood blocks carefully arranged on the matte room floor to serve as a guide for Mark's matte painting |

|

| Mark adding detail to a 1930's period Graumann's Chinese Theatre as part of the birdseye view seen above. |

|

| Another of Mark's ROCKETEER mattes, with Graumann's Theatre once again depicted with a glorious Golden Era vibe. |

Q: One

of the shows you painted some dynamite mattes for was BUGSY starring Warren

Beatty. Now Harrison Ellenshaw told me

horror stories of working with Warren on DICK TRACY as star/director with a

penchant for indecisiveness and changes of mind which drove the effects guys

crazy as deadlines loomed and mattes were painted, repainted, altered and then painted

over back to the way they were to begin with!

I don’t think Warren directed BUGSY but he no doubt had a lot of

control. Any problems along these lines

on BUGSY?

A: No. The matte work on BUGSY might have

been viewed as more of a function of the art department. I mainly talked to the production designer,

Dennis Gassner about the shots. All of

my instructions from Dennis were clear and useful.

There were probably many

matte shots being created in a concurrent fashion for DICK TRACY, and it was

just a few for BUGSY. The exactitude demanded by most traditional matte shot

processes can be exasperating, even just working on ONE shot, sometimes. This

work always looks like fun when it is finished, and that’s why we all love it,

but trying to get several shots looking good, approved and out the door can be

rough.

|

| Location plate for a discrete BUGSY matte shot (see below). |

|

| A remarkably photo real matte painting to bring the forties back into being for BUGSY (1991) |

|

| Painting and plate perfectly merged as one in an invisible trick shot that nobody ever noticed. |

|

| Extraordinary close up detail from the BUGSY matte art shown above. |

Q: The BUGSY view of the Hollywood hills is

a beauty Mark, and of course that jaw dropping night shot of the club on the

boulevard is one of my all time favourites.

It looks as though you’ve used an airbrush there on foreground elements.

A: I generally avoided using an airbrush

if at all possible. You can usually just do the blending and gradations with

normal brushes, but the airbrush is good for things like glows. I painted the lens

bokehs with an airbrush.

Q: I

ask this often of my interviewees – can you explain your own matte process

right from initial art directors’ sketch, through to plate photography,

painting and final marry up.

A: Most of my preferred methods were simply

what I had learned over the years working with people like Jim Danforth, Rocco

Gioffre, and David Stipes, and shots that I have studied by people like

Whitlock, Ellenshaw, Larrinaga, and Pangrazio.

I don’t feel I have ever come up with any new, original or startling way

of doing something.

Starting out I would almost always make a

small design painting, usually about a foot wide, to show to the director,

generally after the plate was shot. Sometimes this small sketch would actually incorporate a color frame blow up

made from the plate, and I would paint around and over it. This is what would

routinely be done nowadays in Photoshop.

Upon approval of the design sketch, I would start the matte painting,

which may have been anywhere from four to six feet in width. If I felt like I had plenty of time, or if

there was some particular effect in the image that seemed better to paint with

oils, I would prefer using them to acrylics or cel vinyls. I liked to use oil

titanium white, because it was such a slow dryer, it could allow for some

elaborate blending effects.

Sometimes I would add a Windsor and Newton product

called Liquin to speed up the drying. Liquin was also helpful as a thinly

applied sealer, once the underpainted area was dry. The sealer would allow you

to paint over a previously painted area without the fresh paint dragging, or

sinking in. Sometimes “oiling out” the surface with an extremely thin layer of

linseed oil, wiped on, is enough to help the smooth application of a new layer

of paint. In terms of setting up the matte line, I was a soft blend guy. I found soft gradual blends easier to do, and

if you had some tiny unsteadiness or flicker in a plate, they could help to

disguise such problems. One thing that

could be helpful with getting a painting started was to have the chemicals and

a place to develop short exposure tests quickly, without having to send a test

to the lab. This kind of test produced a pretty rough looking negative image,

but was usually good enough to check alignment of things like trees, telephone

poles or architectural features that had to line up with precision. The line up

tests and color exposure tests were examined with an eye loupe, while working

on the painting and making adjustments.

|

| The live action plate for the grand centrepiece matte from BUGSY |

|

| Mark and Cameron's final marry up. Need I say more? |

|

| A picture is worth a thousand words..... or 2000 in this case. |

|

| Some more neon detail that Mark kindly sent me, knowing full well my fetish for matte painted neon signs and the like. |

Q: I’ve