It's been a while I know, but I did promise you guys I'd be back, and back I am! I've been touring Europe and Scandinavia with my family and enjoying all manner of cultures and landscapes, ranging from Venice to Lisbon and Tunisia to Copenhagen and Stockholm to Budapest, and then some. It's official.... Barcelona, Spain is THE most beautiful city in the world! You heard it here first... a wonderful place to visit.... and I've been around the globe a fair bit over the years. The only downside were the astonishingly fascist cops there who seemed to relish busting innocent street artists and performers everywhere we looked, as if the joint were still under General Franco's iron fist. Still, a great place, fantasticly insane Dali-esque architecture, super book stores for film and art, beautiful sights and nice people. If it weren't for the fact that it takes around 30 (yes, thirty) hours to get there from New Zealand, I'd go again next month. Living down here at the arse end of the globe can have it's advantages for sure, but travel ain't one of them!

I was recently invited to compile a list of the 10 best mattes of all time for the online magazine Shadowlocked. Well, 10 proved just a tad too lightweight for me so I upped the ante to 50, and that article may be found right here. I wanted to avoid the obvious, popular mattes where possible and have a wide range of genres and era's as an educator to the non matte savvy general reader to appreciate just how mattes can slip by totally unnoticed so often. The editor of Shadowlocked even agreed to install movie clips of several key matte shots as those special shots were difficult to appreciate as a mere static image. I expected all sorts of angry responses to my list (but only got one to my surprise). Regular readers of this blogsite will not be surprised at many of those finalists,with a great many vintage shots in there.

If any readers out there happen to have copies of old (and I mean OLD) American Cinematographer or British Kinematograph with articles on special effects, I would be your friend for life if any kindly souls would contact me in hopes of getting a scanned copy of particular articles. Am.Cine did alot of FX profiles in the 40's especially, with articles on Fulton, Sersen, Kellogg, Ries, Haskin, Dunn and Lerpae - all of whom are of great interest to your humble author. I thank those who have already sent me copies of fantastic articles such as the rare Whitlock article in Film Maker's Newletter among others. It's all very much appreciated and is so helpful for my research.

Anyway, the sad news of Matthew Yuricich's passing eventually caught up with me while between foreign locales so I counted my blessings as it were, that I'd had the unique opportunity to present a great many questions to Matt just a month or so before his death. What follows is a candid, often amusing and always revealing insight into the world of the matte painter as told in his own words. I hope you enjoy the journey.

________________________________________________________________________________

MATTHEW YURICICH:

IN

HIS OWN WORDS

A

few months ago I was contacted by Craig Barron, visual effects supervisor at

Matte World Digital and principal author of the indispensable tome The

Invisible Art – The Legends of Movie Matte Painting, whereby I was presented with the once in a lifetime opportunity to have a

candid Q &

A with legendary matte artist Matthew Yuricich. Naturally I leapt at the chance, though the

vast geographic distance between California and New Zealand proved to be a quandary as I’m not a telephone guy (I never use ‘em)

and Matt wasn’t an email guy. Just as

such a unique once in a lifetime opportunity started to look as though things

wouldn’t pan out, an extremely generous solution was quickly formulated by

Craig with Matt’s friend, visual effects cameraman Peter Anderson. I am most grateful to both gentlemen for

their solid support and really going ‘beyond the call of duty’ to facilitate

the ’on site’ interviews with Matt at his retirement home in Los Angeles.

A

few months ago I was contacted by Craig Barron, visual effects supervisor at

Matte World Digital and principal author of the indispensable tome The

Invisible Art – The Legends of Movie Matte Painting, whereby I was presented with the once in a lifetime opportunity to have a

candid Q &

A with legendary matte artist Matthew Yuricich. Naturally I leapt at the chance, though the

vast geographic distance between California and New Zealand proved to be a quandary as I’m not a telephone guy (I never use ‘em)

and Matt wasn’t an email guy. Just as

such a unique once in a lifetime opportunity started to look as though things

wouldn’t pan out, an extremely generous solution was quickly formulated by

Craig with Matt’s friend, visual effects cameraman Peter Anderson. I am most grateful to both gentlemen for

their solid support and really going ‘beyond the call of duty’ to facilitate

the ’on site’ interviews with Matt at his retirement home in Los Angeles.  Since

this conversation took place in April of this year, Matthew sadly passed away

on 28th May 2012 at

the age of 89, so this document is more than likely his final interview, and I for one feel proud to have been invited to 'chew the fat' with Matt.

Since

this conversation took place in April of this year, Matthew sadly passed away

on 28th May 2012 at

the age of 89, so this document is more than likely his final interview, and I for one feel proud to have been invited to 'chew the fat' with Matt.

The

following article presents Matt’s recollections of his introduction to art and

then into the photographic effects world, told entirely in his own words. The

topics discussed with Matt were wide ranging, the many personalities colourful

– to say the least, the behind the scenes info revealing, and the chronicle of

one of Hollywood’s foremost matte painters - in all probability, the last of

the Golden Era studio matte practitioners, are priceless. It is my hope that this article will be

enjoyed by the many matte art enthusiasts out there – be they industry

professionals or armchair archivists. As

I’ve been told by numerous people who knew and worked with him, Matthew was

indeed ‘one of a kind’.

None of the following chronicle would have

been remotely possible, as outlined above, without the help of Craig and Peter,

to both of whom, I am deeply indebted. A

big thank you too to Michele Moen for kindly agreeing to write the foreword on

her memories of working for Matthew, and a thanks too to Richard Edlund, Virgil

Mirano, David Stipes and Gene Koziki for kindly supplying additional

photographs. Lastly, I’d like to acknowledge Robert Welch for allowing me to

use very rare material on Matt from the A.Arnold Gillespie collection.

None of the following chronicle would have

been remotely possible, as outlined above, without the help of Craig and Peter,

to both of whom, I am deeply indebted. A

big thank you too to Michele Moen for kindly agreeing to write the foreword on

her memories of working for Matthew, and a thanks too to Richard Edlund, Virgil

Mirano, David Stipes and Gene Koziki for kindly supplying additional

photographs. Lastly, I’d like to acknowledge Robert Welch for allowing me to

use very rare material on Matt from the A.Arnold Gillespie collection.

______________________________________________________________________

MICHELE MOEN REFLECTS ON MATTHEW - MENTOR & FRIEND:

|

| Matt's protoge and close friend Michele Moen at work on a matte at Boss Films. |

Matt Yuricich hired me by asking me, in his down-to-earth

manner, if I’d like to wash some brushes and then through the years as my

mentor, he became my life-long friend.

He was very loyal, most of all to his family and then to his

friends. Every Christmas he’d buy all

the ladies at Boss Film Studios a little gift, usually a bracelet or some type

of trinket and have it boxed with a ribbon and then he’d hand me a paper bag of

the gifts and tell me to distribute them after he’d gone home. He said he was too shy (with a twinkle in his

eye). He didn’t want a big fuss to be

made over him yet he was filled with generous and caring gestures. He was a proud gentleman who was a master at

his craft. He taught me that matte

painting was a craft that one learned and practiced. He was also a very talented artist who, in

his free time, painted beautiful landscapes for art galleries but he never

really advertised or promoted himself.

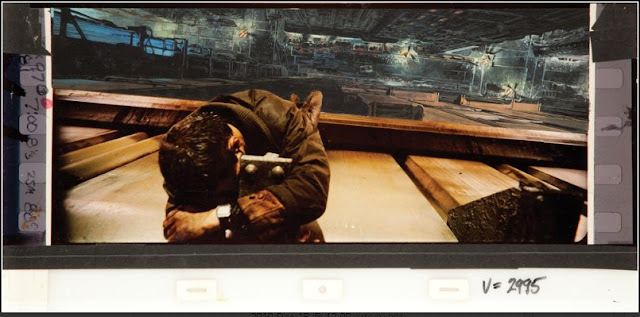

I began as an apprentice on Bladerunner and

the way Matt taught me was to have me sit on a stool behind him and just

watch. He’d come in to the studio really

early in the morning, sometimes at 4:30

or 5 a.m. and do the most important

sections of the painting before the rest of us came in. I’d be in before dailies at 9 a.m. and after dailies I’d watch Matt paint for 2 hours

or so and he’d explain process or point something out. He was a good teacher and patient and I am

lucky to have had that kind of training.

By 3 he’d show me an area on the painting that he wanted me to fill in

or continue painting on. He showed me

how to look at the film frame through the loop every few minutes while I was

applying a stroke to make sure the blend was successful. Look through the loop, look at the painting

over and over until I knew exactly what I was looking for.

I began as an apprentice on Bladerunner and

the way Matt taught me was to have me sit on a stool behind him and just

watch. He’d come in to the studio really

early in the morning, sometimes at 4:30

or 5 a.m. and do the most important

sections of the painting before the rest of us came in. I’d be in before dailies at 9 a.m. and after dailies I’d watch Matt paint for 2 hours

or so and he’d explain process or point something out. He was a good teacher and patient and I am

lucky to have had that kind of training.

By 3 he’d show me an area on the painting that he wanted me to fill in

or continue painting on. He showed me

how to look at the film frame through the loop every few minutes while I was

applying a stroke to make sure the blend was successful. Look through the loop, look at the painting

over and over until I knew exactly what I was looking for.  On Bladerunner, the matte paintings

were shot on a particular film stock so that to get a black color on film, the

paint had to be a muddy, murky grey-green but once a series of dabs of color

stroked on the side of the matte painting were filmed and we could see the

result, we knew what to mix to get that color.

It was all in relation to the film; the painting itself was not a pretty

picture to hang on the wall. Matt

painted with Winsor & Newton long-handled sable brushes and made short dabs

of color almost as an impressionistic style.

He said the film would bring it all together and it did. He smoked cigarettes then and would leave the

cigarette burning in his mouth until the ash fell onto the oil painting; that

was added “texture” which was O.K. Razor

blades scraping away the top wet layer of a lighter brown would become a dirt

road or a tree trunk; random texture that would photograph as realism. I would draft out in pencil the next painting

or project a film clip onto a board or glass and trace in pencil the details so

that Matt could come in the next morning and start a new painting. Also, I’d clean off his glass palette every

night and lay out fresh oil paint in the same order that he’d been working with

for years so that he could reach for a color without looking. At the end of the day, I’d wash often as many

as 50 brushes with an Ivory soap bar in warm water and then place them

carefully in a drying cabinet. If one of

the brushes was a little stiff and not washed properly, Matt would toss it back

into the turpentine-filled container to be washed again.

On Bladerunner, the matte paintings

were shot on a particular film stock so that to get a black color on film, the

paint had to be a muddy, murky grey-green but once a series of dabs of color

stroked on the side of the matte painting were filmed and we could see the

result, we knew what to mix to get that color.

It was all in relation to the film; the painting itself was not a pretty

picture to hang on the wall. Matt

painted with Winsor & Newton long-handled sable brushes and made short dabs

of color almost as an impressionistic style.

He said the film would bring it all together and it did. He smoked cigarettes then and would leave the

cigarette burning in his mouth until the ash fell onto the oil painting; that

was added “texture” which was O.K. Razor

blades scraping away the top wet layer of a lighter brown would become a dirt

road or a tree trunk; random texture that would photograph as realism. I would draft out in pencil the next painting

or project a film clip onto a board or glass and trace in pencil the details so

that Matt could come in the next morning and start a new painting. Also, I’d clean off his glass palette every

night and lay out fresh oil paint in the same order that he’d been working with

for years so that he could reach for a color without looking. At the end of the day, I’d wash often as many

as 50 brushes with an Ivory soap bar in warm water and then place them

carefully in a drying cabinet. If one of

the brushes was a little stiff and not washed properly, Matt would toss it back

into the turpentine-filled container to be washed again.

Other than visiting Matt and

talking to him on the phone, the last big, recent, fun outing together was when

I took my nephew and Matt took one of his grandsons to The Academy Awards in a

limousine. I think he took all his grand

kids and his kids one at a time to the Awards.

I wish he was still here; he had wanted to live to 100.

I really miss his stories; he

remembered everything about every movie he worked on.

Michele

Moen

July 20, 2012

__________________________________________________________________

MATTHEW YURICICH – IN HIS OWN WORDS

|

| One of the many Oscar nominated mattes from THE GREATEST STORY EVER TOLD (1965) |

EARLY FORAYS INTO ART:

I was always interested in art. I can remember my father taking me to school back

in Ohio with 8x10” coloured

sheets of paper and pencils because I was drawing since I was at least 2 or 3

that I can remember. I couldn’t speak a

word of English then, that’s why he took me there, although I was born in this

country, and it just went on from there.

I’m very proud of the fact that the very first thing I did commercially

or professionally was a contest in the paper for, I think, Flash Gordon. It was a whole city and you had to paint it

and I won first prize. I was 12 years

old or something. In The Depression

years that was really something.

I was always interested in art. I can remember my father taking me to school back

in Ohio with 8x10” coloured

sheets of paper and pencils because I was drawing since I was at least 2 or 3

that I can remember. I couldn’t speak a

word of English then, that’s why he took me there, although I was born in this

country, and it just went on from there.

I’m very proud of the fact that the very first thing I did commercially

or professionally was a contest in the paper for, I think, Flash Gordon. It was a whole city and you had to paint it

and I won first prize. I was 12 years

old or something. In The Depression

years that was really something. |

| THE EGYPTIAN (1954) |

ARTISTIC TRAINING & UNCLE SAM:

I had no formal artist training. I was doing the stuff through high school and

I even got permission to take two years of art because you had to take one year

and a year of physics and chemistry and all that, but the art teacher thought

that I showed so much promise… then I went into military service and served in

the US Navy on the USS Nassau in the Pacific theatre of war.

|

| Fred Sersen with his glass shot artists on the Fox lot. |

|

| The grand CinemaScope costumer PRINCE VALIANT (1954) was one of many big Fox shows that Matt painted on. |

HOLLYWOOD BY DEFAULT:

|

| Matt & Betty. A guy in uniform always gets lucky. |

|

| Animated airplanes and tracer fire fx from Matt and Jim Fetherolf for DESTINATION GOBI (1953) |

One day 20th Century Fox

called me and they wanted to hire me for six weeks of frame by frame animation

(rotoscope) work. I didn’t know what the

hell that was…I’d never even heard of ‘24 frames a second’ and all that jazz, but

I quickly found out it was tracing and carefully inking figures, taking them

out of one scene and putting them in another (by hand drawn traveling mattes). This was about 1950 I think. I also was assigned to make the duping boards

(for duplicate matte compositing) at Fox.

|

| The 20th Century Fox Special Photographic Effects department in 1953 under Ray Kellogg. |

We never did originals (original negative mattes) there in those days. We’d have a white board and black out an

area, then you’d have to trace out that area and reverse. It was very critical because that line has to

be perfectly matched. Everybody else had

lines that looked too heavy, and I could never understand that. I always tried to leave a little separation

so the stuff blends together in the shot.

That was one of the things I was doing there under Fred Sersen all the

time.

We never did originals (original negative mattes) there in those days. We’d have a white board and black out an

area, then you’d have to trace out that area and reverse. It was very critical because that line has to

be perfectly matched. Everybody else had

lines that looked too heavy, and I could never understand that. I always tried to leave a little separation

so the stuff blends together in the shot.

That was one of the things I was doing there under Fred Sersen all the

time.  |

| One of Matt's earliest assignments as VFX roto/animator for DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL (1951) |

|

| Jim Fetherolf |

We were working on a picture with Clifton Webb and John Payne – in the film they both died and were sent to heaven. We had to make rotoscope mattes for their ghosts walking through walls and that sort of thing, and I remember for some reason I had an affinity for this stuff. Both Jimmy and I did real fine, even though we had some problems with the frame by frame animation, we both traced accurately.

I did a lot of that rotoscope work back then that people will never know. I learned a lot of useful stuff right away at Fox.

|

| TITANIC (1953) multi part split screen composite. |

|

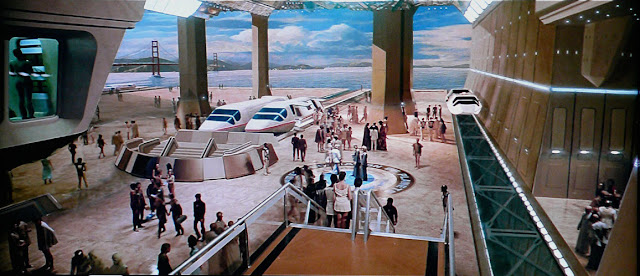

| One of Matthew's most iconic shots - LOGAN'S RUN (1976) |

TEAM PLAYER FOR A SUPERSTAR:

Around this time I wound up on Marilyn

Monroe’s softball team. We won the

championship. She was going out with Joe

DiMaggio at the time. That party up at

her house was something…she chased me all over the damn house. She liked men. I was rather a stick in the mud in those

days, and very naïve…I wouldn’t even dance with another woman because I

was married. I still wake up and have

nightmares of being so stupid. I may

have kept my integrity there, but I’d sure like to have lost my integrity with

Marilyn!

Marilyn had a bad reputation on the

set, but she was a really great gal as far as I was concerned, and to the guys

on her team. She really was alright… she

gave us a baseball autographed by the World Series champion, The New York

Yankees and Joe DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe.

My wife threw it into the incinerator!!!

|

| A wonderful, unused matte composite prepared for SOYLENT GREEN (1972) |

FRED SERSEN & RALPH HAMMERAS:

|

| Ferdinand 'Fred' Sersen |

Sersen was good, and all the credit

to him. Ralph Hammeras was an old friend

and Ralph was the head of the matte department in the earlier days at Fox

before Sersen took over from him, and Ralph was just pushed aside, I don’t really

know why. Ralph had some very

interesting stories and he was almost killed in a bad automobile crash one time.

|

| Ralph Hammeras (at right) |

He did miniatures as well as matte

painting. Ralph was a good artist. They got rid of Ralph because of some

personal stuff and Ralph then worked for Fred.

They brought Fred, and Fred brought Emil Kosa – both Czechoslovakians,

so I guess there was a little something there that I didn’t see. Fred was one of those guys like a real quiet

Santa Claus type, but really rough though.

The man will fool you completely.

He was a very tough guy and very knowledgeable.

|

| Gary Cooper's GARDEN OF EVIL (1954) |

THE MATTE DEPARTMENT PECKING ORDER:

|

| THE DESERT FOX (1951) on which Matt assisted. |

At both MGM and Fox there was no monkey

business. Fred would come over to us and

see what was going on, and he smoked his cigars, and the problem was that when

he told you or gave you orders, he was chomping on his cigar. You couldn’t tell what the hell he was saying

(laughs)… but when it was clear then you paid attention – I remember

that part very well.

I’d occasionally put my two cents in,

not knowing anything at all, but I’d never heard of a suggestion box, if they’d

had one at Fox. They sure never had one

over at MGM. He (Warren Newcombe) would

never go for that just because of principle because he was the ‘Lord and

Master’.

|

| Fox FX cameramen with head Ray Kellogg 2nd from left. |

|

| The not terribly entertaining DEMETRIUS AND THE GLADIATORS (1954) which recycled many mattes from THE ROBE |

EMIL KOSA, JR – ADVERSARY & ANTAGONIST:

His old man smuggled him out of Paris

to get in here. His father (Emil Kosa senior)

was also a matte artist, but his father was nothing like him, either as a

painter or as a person. He (Kosa snr) was

nicer, and although I met him I never worked with him. Kosa jnr was a friend of Ray Kellogg’s, who

became head of department, and Ray befriended him pretty well.

|

| Emil Kosa, jnr |

|

| Kosa in self portrait. |

Emil was an excellent portrait painter, a real traditional artist – but he was very bitter at that time because the abstract stuff that was popular was really hitting the traditional art world hard and I saw Emil try some of those things and I thought they were great. I told Emil that what he should do is to paint something different. Here I am, a little assistant telling him. He came upon his traditional ways when his father smuggled him out of Czechoslovakia in a potato sack...he started as the artists did for the last 400 or 500 years… they learned to grind their own paints and all that stuff in Europe. His father was a great artist too with a great traditional background. Emil’s ballet dancer paintings were just as good, if not better than Degas…and his portraits were just excellent. His matte shots were very good, though at times they’d be a little too tight. He was a prolific painter in mattes. He did most of the work and he was fast. Emil’s private life was kind of sad. He’d lost both his wife and his 11 year old daughter – both of them died. That daughter was his only child.

|

| Matthew again assisted Kosa and Kellogg on KING OF THE KHYBER RIFLES (1953) with VFX animated dust storms. |

KOSA & YURICICH – AN UNEXPECTED APPRECIATION:

|

| Emil Kosa jr plein air painting - late 1940's |

|

| Kosa's gallery art which Matt admired. |

I was after him to take me painting

with him on locations to paint gallery stuff and he never would. Kosa must have thought I was capable because

he came to MGM one day years later and looked to see what I was doing there,

and I was doing Mutiny on the Bounty – squeezed (for CinemaScope) ships and all

that, and he was quite impressed. And

then I went to one of his art lectures on La Sienna

Avenue, and he’s painting a subject and describing

it and he spotted me and my brother in the audience and he stopped and he said “I’d like you to meet one of the finest

portrait painters” and “here is

Matthew Yuricich.” I had to stand up

and everybody clapped and all that.

Later when I got to talk to him I said “How can you say all that stuff…you never let me paint… you never let

me do anything… you don’t know what the hell I can do” Emil said, he saw my work at MGM on Bounty and

he remembered that portrait I did back at Fox.

I was after him to take me painting

with him on locations to paint gallery stuff and he never would. Kosa must have thought I was capable because

he came to MGM one day years later and looked to see what I was doing there,

and I was doing Mutiny on the Bounty – squeezed (for CinemaScope) ships and all

that, and he was quite impressed. And

then I went to one of his art lectures on La Sienna

Avenue, and he’s painting a subject and describing

it and he spotted me and my brother in the audience and he stopped and he said “I’d like you to meet one of the finest

portrait painters” and “here is

Matthew Yuricich.” I had to stand up

and everybody clapped and all that.

Later when I got to talk to him I said “How can you say all that stuff…you never let me paint… you never let

me do anything… you don’t know what the hell I can do” Emil said, he saw my work at MGM on Bounty and

he remembered that portrait I did back at Fox.

TRANSITION INTO MATTE PAINTING:

|

| Yuricich glass shot set up: UNDER THE RAINBOW (1983) |

|

| CALL ME MADAM (1953) - Ralph Hammeras matte shot. |

|

| Fox Artist Menrad von Muldorfer (left) |

|

| The very dull bio-pic DESIREE (1954) with a miscast Marlon Brando as Napoleon. |

THY MATTE PAINTER SHALL PAINT, AND ONLY PAINT:

|

| Lee LeBlanc at Fox |

|

| Intended matte shot final design for BEN HUR (1959) |

|

| POLTERGEIST II - THE OTHER SIDE (1986) |

|

| Dazzling, flickering neons from LOVE ME OR LEAVE ME (1955). My own personal favourite matte genre...sublime! |

DAZZLING NEONS & SPECTACULAR SHOWCASES:

Those big theatre marquees….I did a lot

of them. I tell you, I must have worked

on 50 theatre fronts and animated the lights.

I was drilling out the holes for the bulbs and backlighting them. We did all that stuff for movie marquees and

we did an awful lot of that as double exposure and we used to use the punched

holes. Mark Davis was doing most of this

sort of work at MGM, he really liked that stuff.

Those big theatre marquees….I did a lot

of them. I tell you, I must have worked

on 50 theatre fronts and animated the lights.

I was drilling out the holes for the bulbs and backlighting them. We did all that stuff for movie marquees and

we did an awful lot of that as double exposure and we used to use the punched

holes. Mark Davis was doing most of this

sort of work at MGM, he really liked that stuff.

I’m trying to think of these other matte

artists. One of them had a bad back or

something and he was doing a lot of scenic work too. He designed and built a motorized chair on

rails so he could roll back and forth while painting matte shots and different

things. His name was Lazini or Muselini

or something like that. We did all the

marquees and signs, they were all painted, even those with 1000 bulbs glittering

underneath.

FIRST MATTE PAINTED SHOT:

|

| Matt's first actual painted matte - from CALL ME MADAM |

If I was painting one of those big

ornate ceilings, if you painted as though you were doing the actual plastering

of all of those curly Q’s and fleur de

lis and all that stuff, and all very precise, it would look like a polished

piece of painting…that’s what it would be like.

Your eye might go to it. Well,

there were a lot of paintings where I had to do that though. I had to paint it so the painting looked like

a finished shot.

If I was painting one of those big

ornate ceilings, if you painted as though you were doing the actual plastering

of all of those curly Q’s and fleur de

lis and all that stuff, and all very precise, it would look like a polished

piece of painting…that’s what it would be like.

Your eye might go to it. Well,

there were a lot of paintings where I had to do that though. I had to paint it so the painting looked like

a finished shot.

If you’ve got a good design, things

go and will fit. Some paintings fall

into place. If you’ve got a lot of

vegetation or foliage, that takes a lot of good expertise which Albert Whitlock

was good at and Mark Sullivan is fantastic at and as I say, he’s the best in

the business right now. They really had

a feeling for that stuff.

WARREN NEWCOMBE – ECCENTRIC OVERLORD:

|

| Warren Newcombe, circa 1930's |

Newcombe had a lot of power,

because when he got going, that was a mystery department at MGM. He just didn’t let anyone know just what he

was doing, so they figured out they’d just better not get him angry, because he

was weird (laughs)…to say the least!

You just couldn’t come on up there to see what we were doing for him (Newcombe). From his desk you could see through the door

and anybody who came upstairs he just wouldn’t let them come in. Even the windows were painted over in black.

Mark Davis became the cameraman for

Newcombe, but Newcombe treated him like something else – poorly in fact. He would take Mark out on location to shoot

the plates and he (Newcombe) would take his brushes and clean them on Mark’s

hair! Mark put up with a lot, though he

was a real clever guy and was able to figure out a lot of technical stuff. He used to tell me that his wife used to get

mad at him for letting Warren do

these things to him. Mark was very

creative and would take a lot of junk from surplus stores and he would create

things (effects gags) and they would work.

He was inventing stuff and he turned out to be a good cameraman but he still

got ‘beat up’ by Newcombe. I don’t think

Newcombe ever knew any of those technical things. Mark came in to MGM when Newcombe was

assistant boy there and he left the studio about ’56 or ‘57.

Did Newcombe make suggestions to us?…he

left the guys alone and every now and then he’d make suggestions, but we never

followed his instructions (laughs)… he was‘The Mad Hatter’, exactly that!

Newcombe did paint mattes

back at the beginning in the 20’s, but to me he couldn’t paint and wasn’t

really a top artist…his own paintings were all very stylized, but he was a

painter and would hold the brush like a hammer.

He did some lithographs and stuff.

In the old days the matte shots were done by his friend that he brought

with him from New York – he

was a real artist… he did all the work. They

had some 20 other guys there they hired during the war while the regular matte

artists had to go away, and their mattes were atrocious. There were a lot of artists in those days who

were matte artists only because they were the first ones to know about it.

Newcombe did paint mattes

back at the beginning in the 20’s, but to me he couldn’t paint and wasn’t

really a top artist…his own paintings were all very stylized, but he was a

painter and would hold the brush like a hammer.

He did some lithographs and stuff.

In the old days the matte shots were done by his friend that he brought

with him from New York – he

was a real artist… he did all the work. They

had some 20 other guys there they hired during the war while the regular matte

artists had to go away, and their mattes were atrocious. There were a lot of artists in those days who

were matte artists only because they were the first ones to know about it.

I’d like to look into Newcombe’s

death and backtrack to see what happened.

He was murdered in Mexico…he’d warned me to stay away and that it was

all pretty dangerous and in his letter he tells me not to come down because

it’s very dangerous in Mexico…though I sure was curious.

|

| Period costumer matte shot from THE KING'S THIEF (1955) |

HENRY HILLINCK – MENTOR & TEACHER:

Henry was a superb artist… he was

the head of the scenic department at RKO or somewhere… a very good craftsman…

he was the president of the union local. He could draw well. He was in the scenic department so he had

some background in it. A lot of the

scenic artists turned out to be good matte artists. Henry let me do a lot of stuff when I first

started there. He said “just keep painting”. I remember when I first painted and when I

was doing paintings for myself, but practicing matte shots while at MGM, and I

talked to him about it and I said, “What

do you think?” He said, “Put it away and look at it after you’ve

painted another 100 paintings and then you’ll see where it fits”.

Henry was a superb artist… he was

the head of the scenic department at RKO or somewhere… a very good craftsman…

he was the president of the union local. He could draw well. He was in the scenic department so he had

some background in it. A lot of the

scenic artists turned out to be good matte artists. Henry let me do a lot of stuff when I first

started there. He said “just keep painting”. I remember when I first painted and when I

was doing paintings for myself, but practicing matte shots while at MGM, and I

talked to him about it and I said, “What

do you think?” He said, “Put it away and look at it after you’ve

painted another 100 paintings and then you’ll see where it fits”.  He taught me the razor blade technique for

texturing the painting…it was just beautiful.

I’d wanted to go into painting for galleries using that razor technique,

but it would have taken forever to do a painting that way, so I continued using

it just for matte shots as there were no other matte artists using it. I picked up a lot from Henry Hillinck. The

razor blade is great for ground texture like in Forbidden Planet… it was great

because you had these phony looking mountains in it and you have your grain on

the masonite.. you just put paint on it and just scrape it to create texture. You couldn’t use it at all times, just for

certain places. I painted some of the rocks and stuff… I was lucky there

because Henry would let me paint and it looked great to me then and I was

thrilled because I got to work on it, though when I look back it looks a little

stiff. Michelle (Moen) picked up the

razor blade technique too… she’s like a veteran with it.

He taught me the razor blade technique for

texturing the painting…it was just beautiful.

I’d wanted to go into painting for galleries using that razor technique,

but it would have taken forever to do a painting that way, so I continued using

it just for matte shots as there were no other matte artists using it. I picked up a lot from Henry Hillinck. The

razor blade is great for ground texture like in Forbidden Planet… it was great

because you had these phony looking mountains in it and you have your grain on

the masonite.. you just put paint on it and just scrape it to create texture. You couldn’t use it at all times, just for

certain places. I painted some of the rocks and stuff… I was lucky there

because Henry would let me paint and it looked great to me then and I was

thrilled because I got to work on it, though when I look back it looks a little

stiff. Michelle (Moen) picked up the

razor blade technique too… she’s like a veteran with it.

Henry was more of a loose painter,

although he could sometimes be very tight in style. I remember when he used to fight Newcombe all

of the time on this ‘modern painting’ thing…abstracts were all garbage… anybody

could do it.

|

| Henry Hillinick full painting from FORBIDDEN PLANET (1956) which Matt assisted with some of the rocks. |

I remember one of Henry’s mattes

that he was experimenting with painting impasto

– real thick. These hanging chandeliers, they had a half dome, and instead of

painting them in 3D, he actually put thick, sculpted paint to see if it was

any different than painting in the 2 Dimensional.

|

| Close detail of Henry Hillinick's matte painting. |

|

| Atmospheric closing shot from BEN HUR (1959). |

HOWARD FISHER – GENTLEMAN MATTE ARTIST:

Howard was a really nice guy… he

was an MGM matte artist and also one of the nicest guys you’d ever find – a

very nice gentleman. Howard must have

been around 65 back in 1955. They hired Howard away from some other

studio. There was a lot of jealousy in

those days.

|

| Howard Fisher's iconic FORBIDDEN PLANET shot. |

Now Howard was more of a photo realist

in his painting, Henry had the feel and could paint it as though he were

standing 10 feet away. At MGM when I

first got there you were so close to the painting, you couldn’t get further

away. Each camera stand was enclosed and

the easel was just out about 5 feet. You

couldn’t paint that loose as you could from if it was 10 to 15 feet away. That’s what most artists can do. Warren

once said to me: “I want you to copy

Henry’s painting here…I want to see how good you do with a painting.”. He couldn’t tell them apart when I got

through.

When they ran matte shots in the

projection room at MGM, they didn’t loop it (spliced onto a continuous 35mm

loop). They cut the matte in with a production

shot before and a shot after and ran it that way. You’d be surprised how many times people

watching these said what are we supposed to be looking at? They didn’t know. But if you run the matte on a continuous loop

you’re going to see every disease that there is in there, and the painting at

it’s best is no way close to looking real.

When they ran matte shots in the

projection room at MGM, they didn’t loop it (spliced onto a continuous 35mm

loop). They cut the matte in with a production

shot before and a shot after and ran it that way. You’d be surprised how many times people

watching these said what are we supposed to be looking at? They didn’t know. But if you run the matte on a continuous loop

you’re going to see every disease that there is in there, and the painting at

it’s best is no way close to looking real. |

| DESTINATION GOBI (1953) |

|

| THE MONSTER SQUAD matte shot for Boss Films. Michele Moen also painted on this picture. |

NEWCOMBE AND THE DUPY DUPLICATOR:

|

| LOVE ME OR LEAVE ME |

|

| The Dupy camera set up at MGM |

|

| Mark Davis & Newcombe |

The camera moves were recorded on a wax disc by the sound department and they wanted control of it all, and that’s what really fouled up Newcombe… he didn’t like that, as it was a ‘matte shot’ and Newcombe wanted full control. Each department was a kingdom in it’s own, and the Dupy Unit was a separate unit (Olin Dupy was the MGM sound technician and inventor)… but at least they were trying something new. That was probably the earliest motion repeating system ever built.

|

| THE EGYPTIAN (1954) |

ANAMORPHIC ANTICS WITH CINEMASCOPE & CAMERA 65:

The Robe was at Fox…I did a big

glass shot where the donkey is riding towards the city of Jerusalem. They had two big pieces of glass framed in

wood and we’re in the middle, we had a tree so it hid the frame. I had done

mattes before that but never a true ‘glass’ shot. I had never seen a glass shot until

then. We didn’t paint our mattes in the

studio on glass in those days – everything was done on masonite or over photo

enlargements but I did it plenty of times since then I tell you.

|

| One of the magnificent mattes from KING OF KINGS (1961). Among the best mattes of the Biblical genre. |

It was very difficult to paint

squeezed, and to get your perspective correct and all of that. When I started on the first anamorphic

picture, The Robe, the scope lens was being used on the main production (**image

photographed in a vertically compressed format and later projected theatrically

through an anamorphic lens to horizontally uncompress the original image to

usually 2 ½ times the normal frame width) . They had colour problems with that process too. Everything was going red, I don’t know

why. That was another enigma with Emil

Kosa on The Robe… we had a big glass shot and Jim Fetherolf and Lee LeBlanc

started painting walls and rocks. I came

in with the second crew with Emil and he say’s “Wash it off!” I said, “What?” He said “Wash it off!” Jimmy was

what you’d call a photo realist and Emil was trying to get me to wash it off

because you’re never going to see it (so much detail). Emil had me mix some great colour and he

painted the whole thing. Emil’s

paintings were up and down in consistency and some on The Robe were so stiff –

the architecture was too rigid.

It was very difficult to paint

squeezed, and to get your perspective correct and all of that. When I started on the first anamorphic

picture, The Robe, the scope lens was being used on the main production (**image

photographed in a vertically compressed format and later projected theatrically

through an anamorphic lens to horizontally uncompress the original image to

usually 2 ½ times the normal frame width) . They had colour problems with that process too. Everything was going red, I don’t know

why. That was another enigma with Emil

Kosa on The Robe… we had a big glass shot and Jim Fetherolf and Lee LeBlanc

started painting walls and rocks. I came

in with the second crew with Emil and he say’s “Wash it off!” I said, “What?” He said “Wash it off!” Jimmy was

what you’d call a photo realist and Emil was trying to get me to wash it off

because you’re never going to see it (so much detail). Emil had me mix some great colour and he

painted the whole thing. Emil’s

paintings were up and down in consistency and some on The Robe were so stiff –

the architecture was too rigid. |

| Both this and above matte are from BEN HUR (1959) |

The very first week I started at

MGM, Cinemascope had just come in and MGM still wasn’t sure about scope so all

of the matte shots were done two ways – in scope and regular – I got to paint the regular…while Henry and

Howard worked on the scope. I complained

that we didn’t have enough space. If you

paint full paintings for 65mm we needed about 20 feet just for the matte stand,

so everything had to be painted squeezed for Clarence’s photography. Later on Ben Hur we shot in MGM’s Camera 65

format. On the sides of the frame it had

a lot of squeeze, which flattened out toward the middle of the frame. The squeeze had something to do with quality,

but to me there would be more quality in a straight spherical lens than in that

widescreen process.

The very first week I started at

MGM, Cinemascope had just come in and MGM still wasn’t sure about scope so all

of the matte shots were done two ways – in scope and regular – I got to paint the regular…while Henry and

Howard worked on the scope. I complained

that we didn’t have enough space. If you

paint full paintings for 65mm we needed about 20 feet just for the matte stand,

so everything had to be painted squeezed for Clarence’s photography. Later on Ben Hur we shot in MGM’s Camera 65

format. On the sides of the frame it had

a lot of squeeze, which flattened out toward the middle of the frame. The squeeze had something to do with quality,

but to me there would be more quality in a straight spherical lens than in that

widescreen process. |

| Matthew at work on his grandest painted matte - for BEN HUR. Mattes were split between Lee LeBlanc and Matt. |

The big matte shot in Ben Hur, we had

real troops for some of it – they marched up and turned right. So I took these real troops and reduced them,

and reduced them and then painted more, so there’s like 3 or 4 columns of the

same troops, repeated optically, and the rest were just painted people. On each side of the procession were real

soldiers. We had to make several tests

because we could see problems in the tests.

Lee insisted on painting the 3-point perspective stuff, with the columns

painted almost leaning over to accommodate that squeeze, and Clarence would scream

at him and say it doesn’t look right, and Lee would say “Well that’s the way you’re photographing it”. He said that it’s the goddamned lens, it

isn’t the human eye at fault.

The big matte shot in Ben Hur, we had

real troops for some of it – they marched up and turned right. So I took these real troops and reduced them,

and reduced them and then painted more, so there’s like 3 or 4 columns of the

same troops, repeated optically, and the rest were just painted people. On each side of the procession were real

soldiers. We had to make several tests

because we could see problems in the tests.

Lee insisted on painting the 3-point perspective stuff, with the columns

painted almost leaning over to accommodate that squeeze, and Clarence would scream

at him and say it doesn’t look right, and Lee would say “Well that’s the way you’re photographing it”. He said that it’s the goddamned lens, it

isn’t the human eye at fault. |

I remember in Ben Hur, Lee painted this

shot with these statues of horses rearing up on the right hand side. So I’m telling Lee, who’s my boss, “Lee, you’re too dark and those horses on

the side are going to have asses 3 feet wide in anamorphic.” He didn’t allow for the correct squeeze. So on the test, those horses butts were clear

across the room and blacker than a piece of coal. Of course it was a learning process too for

Lee. I don’t know why Lee didn’t know

because he had been painting mattes for years.

|

| Barely detectable matted in city, lake and mountain range from THE DUCHESS AND THE DIRTWATER FOX (1976) |

UNIONS, POLITICS AND DEADLINES:

The Hollywood strike of 1957, Henry

said you’re in the union and you can’t paint and all that stuff, and I said “I’m not going to, but Henry, you told me

yourself in 1945 when the big strike was on, you got a building across the

street or somewhere, and you guys did the matte shots over there. What’s the difference?” Well, as it turned out Ray Clune, head of

productions who I knew from 20th Century Fox called up Lee LeBlanc…

things were slow, and he knew everybody, he said “You’ve got to lay Matt Yuricich off.” And I remember Lee, he said,“I

can’t do that. He’s doing a lot of work”. There was some kind of…. it wasn’t really a

strike, but there was a problem and I had to go. I went to Columbia

in 1957 and I worked with Larry Butler.

Because he wanted me back, Lee called, and I said “I’m not going back to that place.

I’m doing full matte work here as a first assistant. At Columbia, these people let me do it”.

The Hollywood strike of 1957, Henry

said you’re in the union and you can’t paint and all that stuff, and I said “I’m not going to, but Henry, you told me

yourself in 1945 when the big strike was on, you got a building across the

street or somewhere, and you guys did the matte shots over there. What’s the difference?” Well, as it turned out Ray Clune, head of

productions who I knew from 20th Century Fox called up Lee LeBlanc…

things were slow, and he knew everybody, he said “You’ve got to lay Matt Yuricich off.” And I remember Lee, he said,“I

can’t do that. He’s doing a lot of work”. There was some kind of…. it wasn’t really a

strike, but there was a problem and I had to go. I went to Columbia

in 1957 and I worked with Larry Butler.

Because he wanted me back, Lee called, and I said “I’m not going back to that place.

I’m doing full matte work here as a first assistant. At Columbia, these people let me do it”. |

| ATLANTIS - THE LOST CONTINENT (1960) |

|

| One of Matt's last trick shots, for UNDER SIEGE II (1995). The entire upper half of the frame is painted on glass. |

MEMORIES OF FELLOW MATTE ARTISTS:

|

| Ray Kellogg |

Ray Kellogg… Ray Kellogg

started as a matte artist but he was really Sersen’s right hand man. He was a tough guy and a very strong,

aggressive individual. He did all of the

shooting on the sets of all of the shots for Fred and he eventually took over

the department. Ray would say things to

me like “How many push ups can you do?” and being young and not very tactful, I said “one more than you can do”. This is unheard of to talk like this to the

guy. He jumped down and did 25. I could never do more than 10 in my whole

life. My muscles just….. I did 26! When Fred retired they kept him on as a sort

of advisor because they weren’t sure Ray could handle the whole department.

|

| Jim Fetherolf fine art |

Jim would go on to work later with Albert Whitlock over at Disney. Albert liked Jimmy too. Apparently they were very friendly.

Lee LeBlanc… I helped him at MGM and he was enough of a politician

to eventually make it to head of department.

I don’t know how he did that… he just felt that he was top artist, and

that wasn’t hard for him. I remember on

one black and white picture at Fox, Viva Zapata, Lee was having some problem,

he was painting this particular shot of a ceiling, and he was arguing with

somebody who said the ceiling isn’t quite right and you can’t see the design properly. Lee painted in two dogs screwing and things

like that up there. They photographed it

and it looked just like a beautiful, ornate ceiling.

Lee LeBlanc… I helped him at MGM and he was enough of a politician

to eventually make it to head of department.

I don’t know how he did that… he just felt that he was top artist, and

that wasn’t hard for him. I remember on

one black and white picture at Fox, Viva Zapata, Lee was having some problem,

he was painting this particular shot of a ceiling, and he was arguing with

somebody who said the ceiling isn’t quite right and you can’t see the design properly. Lee painted in two dogs screwing and things

like that up there. They photographed it

and it looked just like a beautiful, ornate ceiling.

Menrad von Muldorfer… Yes he was at Fox. His dad actually built the studio, so I guess

he got in through that end. Von

Muldorfer worked on all of those early big Fox films… The Rain’s Came and In

Old Chicago and later on Cleopatra and

others… they were all big shows.

Albert

Maxwell Simpson… In the old days, Al Simpson was another big matte painter.

He was one of the real old timers and he was used mainly to ‘work’ the matte

line. They had soft blends and he had

the patience to sit there and green by green touch up and eliminate that whole

matte line that was showing. That was

all pretty tricky work where he’d view the tests with the painting overlapping

the live action. There was always

something to it…he’d go in and it’s amazing just how well that worked. You’d get there with patience, and Simpson

was known for that, and that’s what they used him for – a sort of a ‘pinch

hitter’ for solving the blend…exactly that.

|

| Cliff Silsby at Fox |

Max

de Vega… Another one of the real old timers. I knew him though there’s no real special

story. He gave me a lot of the

background on the previous Fox matte artists.

He helped me out a lot and taught me the tradition of the art. He gave me a lot of information about staying far away from Kosa, that’s for

sure (laughs). Fox had a big department

with a lot of resourses, and I utilized it and learned a lot of stuff.

Jack Shaw… Jack and I were

pretty good friends. He committed

suicide. Jack could not take the

constant direction from everybody, and Clarence Slifer told me that he did have

one failing thing that he’d just keep on painting – that they’d have to pull it

(the matte painting) away from him! I

saw him paint and what a good matte artist.

I wanted to find out more about the matte painting and stuff and Jack

was telling me it’s just too difficult when you have people that don’t know

anything about painting telling you how to paint. It bothered the hell out of him. He was a good man.

Lou

Litchtenfield… Lou had started with Paul Detlefsen and Mario Larrinaga at

Warner Brothers before the war…I knew Lou pretty well. I’ve seen a lot of his work and it was pretty

good. He went to Warners and set up an

optical department. Warner Bros had

quite a contingent of good matte artists, and Lou told me that when he was

working on The Fountainhead and there was a big, tall building that he’d

designed and all that, and he was going to paint it in oil and he used lacquer

thinner and the oil paint ‘ran’ by mistake.

Lou called Mario and he came in and they worked all night to repair that

matte painting. I can imagine the

problem.

Lou

Litchtenfield… Lou had started with Paul Detlefsen and Mario Larrinaga at

Warner Brothers before the war…I knew Lou pretty well. I’ve seen a lot of his work and it was pretty

good. He went to Warners and set up an

optical department. Warner Bros had

quite a contingent of good matte artists, and Lou told me that when he was

working on The Fountainhead and there was a big, tall building that he’d

designed and all that, and he was going to paint it in oil and he used lacquer

thinner and the oil paint ‘ran’ by mistake.

Lou called Mario and he came in and they worked all night to repair that

matte painting. I can imagine the

problem. George

Gibson (Scenic Artist)…

George

Gibson (Scenic Artist)…George’s thing at MGM was head of Scenic Art, and it’s just unbelievable how good these guys were (scenic art department). You come up there to look at those backings and you can’t tell a thing. The brush strokes are 4 inches wide and you step back just like it was designed for…I mean it was just unbelievable how great the finished thing was. When you’re painting a thing like that, you are 2 or 3 feet away, you have to know what you’re doing even though it looks like you can’t tell what you’re seeing. That’s the same thing with matte shots. You’re painting for the camera and those who have the advantage of painting that same way and same distance for their whole career, they can do it standing backwards, and the same thing with painted backing. Henry Hillinck had that experience although his backings were nothing compared to George Gibson.

Irving

Block… I found paintings in storage from Julius Caesar that I tracked down

that Irving had done, maybe in 1950

or thereabouts…mainly painted over photo blow ups as I recall. He would always

be huddled over his painting whenever anyone came into the room. He’ll be

painting it like he’s hiding in a corner.

He’ll be turning with his back, so if you walked by you only saw his

back, but he was always doing something.

I later worked for Irving and his partner Jack Rabin on that race

picture, Death Race 2000.

Rocco Gioffre… I brought

Rocco out here from high school in my old hometown in Loraine,

Ohio for Close Encounters, and I got him

started. I didn’t know him back in Ohio. When later on I worked with Rocco, we did it all

on original negative, and we could make them match right there, and it kind of

took me back. I had kind of forgotten it

all. There’s nothing better than the

original negative… it’s like comparing night and day. You can take the same painting that doesn’t

look too good on a dupe, and it works fine as an original.

Rocco Gioffre… I brought

Rocco out here from high school in my old hometown in Loraine,

Ohio for Close Encounters, and I got him

started. I didn’t know him back in Ohio. When later on I worked with Rocco, we did it all

on original negative, and we could make them match right there, and it kind of

took me back. I had kind of forgotten it

all. There’s nothing better than the

original negative… it’s like comparing night and day. You can take the same painting that doesn’t

look too good on a dupe, and it works fine as an original.

Jack

Cosgrove... Clarence Slifer would tell me about Jack Cosgrove, because he

worked for Jack for years and he said that he was the sloppiest painter. He’d drop his cigarette ashes and they would

be all in the painting, and there was dirt and everything in it, and he said “But boy, it sure looked good”. At Selznick when Clarence was there with

Cosgrove, they had terrific matte paintings.

Spencer

Bagtoutopolis… Spencer was an older man and, painting wise, he was the best

because he’d had 60 years experience of painting that way…there was no

impressionistic stuff to his work… everything was precise and done right and

with a feel, yet done fast…the guy was training all his life and he didn’t know

it. Living in a time where guys weren’t

photographing, he had to get these illustrations out real fast. There were assignments Spencer was painting

for the King and Queen! He was sent all over the world, especially India. He was

80 when he was working for Clarence. Spencer

and Clarence (Slifer) had some sort of big falling out though.

Peter Ellenshaw… Peter Ellenshaw was a master. My then wife and I were once driving by The

Laguna Beach Art Museum, and the road is quite a ways from the gallery windows

and entrance, and there are paintings there in the windows. I said “Stop

the car!” She says, “What’s the matter?” I said,

“There’s a matte shot artist that has some paintings in there!” She then says “Those are all seascapes”. I

said, “I don’t give a damn…I know a matte

shot technique when I see one”. It

was Peter Ellenshaw’s work. From 200

feet away I could tell there was a matte painting technique there. You look at Peter’s stuff that he did for

Spartacus and Quo Vadis… what beautiful shots

Peter used a lot of the old tricks on Darby O’Gill. He’s a guy that not only paints matte shots,

he supervised that whole thing and it was fantastic. I envy him having Percy Day show him how to

paint. Peter was able to learn the craft

and carry it on. Peter saved some of his

paintings, and I had one of them at MGM…it was on glass, already cracked, from

Quo Vadis.

Michele

Moen… I remember Michele was painting a city thing, and she wanted to do

the toughest shot. She was a very

aggressive gal, very ambitious and very talented. She said “There’s

something wrong with it.” I said to

her, “Step back here.” I could see the problem as I walked by and I

thought I’d let her sweat it out, as it’s the only way to learn. Well, a third of the painting or more, the

buildings looked like they were down into a 100 foot hole. It was a very simple thing and when I showed

her she corrected it because you tend to get so used to your painting while

you’re painting, and you look at it and it looks fine, and until you see it on

a screen, you then look at it and it ain’t fine.

Michele

Moen… I remember Michele was painting a city thing, and she wanted to do

the toughest shot. She was a very

aggressive gal, very ambitious and very talented. She said “There’s

something wrong with it.” I said to

her, “Step back here.” I could see the problem as I walked by and I

thought I’d let her sweat it out, as it’s the only way to learn. Well, a third of the painting or more, the

buildings looked like they were down into a 100 foot hole. It was a very simple thing and when I showed

her she corrected it because you tend to get so used to your painting while

you’re painting, and you look at it and it looks fine, and until you see it on

a screen, you then look at it and it ain’t fine. |

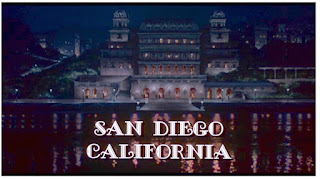

| EARTH II (1971) |

Jim got to know my work and I had seen his, and then what happened was

that we’d get lulls and there was nothing to do, and I’d go into the little

camera room, which was all glass and you could see in there, and Art

Cruickshank came up to me in the room and said “It would be smarter if you went somewhere where you can’t be seen when

you’re reading a book”. I said, “Art…I got nothing to do right now, if you

don’t need me let me know and I’ll leave…I’m not hiding for anybody. If I have work, I’ll do it…..if I don’t have

it I’m going to do……” And Jim just started clapping. He loved that.

Jim got to know my work and I had seen his, and then what happened was

that we’d get lulls and there was nothing to do, and I’d go into the little

camera room, which was all glass and you could see in there, and Art

Cruickshank came up to me in the room and said “It would be smarter if you went somewhere where you can’t be seen when

you’re reading a book”. I said, “Art…I got nothing to do right now, if you

don’t need me let me know and I’ll leave…I’m not hiding for anybody. If I have work, I’ll do it…..if I don’t have

it I’m going to do……” And Jim just started clapping. He loved that. |

| The unfathomably bizarre Audrey Hepburn vehicle, GREEN MANSIONS (1959) |

THE LIFE AND DEATH OF VINTAGE MATTE ART:

I knew every painting that was left at

Fox. It broke my heart to burn most of

them up. Of course 9 out of 10 it didn’t

matter. There were some good ones. The only ones that were left were the ones

they happened to paint on glass or masonite or things like that, and they had

quite a few because this was from years of collecting.

I knew every painting that was left at

Fox. It broke my heart to burn most of

them up. Of course 9 out of 10 it didn’t

matter. There were some good ones. The only ones that were left were the ones

they happened to paint on glass or masonite or things like that, and they had

quite a few because this was from years of collecting.

When I went through these old pictures,

I mean the matte paintings in storage, there were close to 4000 – everything

was numbered – there were no titles on them.

It seemed like they neglected the matte shots and there were superb

paintings, and some of them that go way back.

They had a lot of cutouts and painted mountains and stuff like that,

pastels, and I used to take them home for my kids’ train set and put them all

around it. When I was working I knew the

shots by their numbers. I’m working on

1342 or 4031 and production number with it.

During one of the lay off periods, when things were very slow I set up a

system of filing these paintings because now we could save them. In storage, each one had a nice tissue paper

over the top and was protected and slotted and everything else. It’s all gone forever.

I remember when MGM opened up the

hotel in Las Vegas, they had a lot

of paintings and they had a sort of studio thing in there then.

|

| Painted sky and island split screened with a gentle optical ocean roll comp for MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY (1962) |

MATTE SHOT PREPARATION:

At that time at MGM there was

Henry, Howard Fisher and Bill Meyer who was a draftsman that drew in the matte

shots when I first got there, and I thought Bill did a great job. So he would mostly draw architectural

stuff. He would draw the buildings and

everything…all he did was to draw these things in, and the lines were like an

indelible blue… they would bleed through.

Bill did nothing but draw this stuff and then you just filled in the

spaces. Then Bill was gone and I’m

trying to think of who else was there before… of course Lou Litchtenfield was

there for a while, but not very long.

At that time at MGM there was

Henry, Howard Fisher and Bill Meyer who was a draftsman that drew in the matte

shots when I first got there, and I thought Bill did a great job. So he would mostly draw architectural

stuff. He would draw the buildings and

everything…all he did was to draw these things in, and the lines were like an

indelible blue… they would bleed through.

Bill did nothing but draw this stuff and then you just filled in the

spaces. Then Bill was gone and I’m

trying to think of who else was there before… of course Lou Litchtenfield was

there for a while, but not very long. |

| THE WIND AND THE LION (1975) |

When I got to MGM the artists there

would make sure it would take at least three weeks to finish a matte. Some were intricate, but there were a lot of

shots that I, as an assistant, could bang out in three days – unless you ran

into problems. Sometimes you could do it

in one day and then do three weeks worth trying to fix the one thing that was

wrong We had this one at MGM with lights

drying it. I got to where I was using a

spray fixative. You had to be careful –

it’s like doing 10 coats instead of 2 – sometimes the heat would crinkle the

painted surface. It would start drying

and already start crinkling. That was a

matte artist’s dilemma when he just had to get things done. Nobody understood that it takes time to dry. None of our mattes were original

negative. All matte shots were done as

opticals.

CLASSIC ERA PASTEL MATTE ART AT MGM:

|

| Incredibly fine detail achieved with sharp pastel pencil and crayon. |

|

| MGM matte painter Rufus Harrington in 1939 working with pastels on a typical Newcombe shot. Note the pastels laid out to the right of this photograph. *Picture courtesy of Craig Barron |

|

| ICE STATION ZEBRA (1968) |

TOO MUCH DETAIL AND NOT ENOUGH FEELING:

I’m trying to think of the movie…I

remember a movie we were on about Vikings (Prince Valiant) with a Viking ship

out at sea and we’d painted a whole fleet of these and every one of these the

sides were decorated with shields, and on the shields we painted tiny detail

that you could see with a magnifying glass.

Emil Kosa had us paint it over and completely start again.

|

| PRINCE VALIANT |

|

| UNDER THE RAINBOW |

|

| Paris in THE 4 HORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE (1961) |

I talked to the old time artists doing

everything very precise because, evidently, the clarity of the film and stuff

wasn’t as good then.

SHAMELESS LOSS OF THE ARTFORM:

When Kerkorian finally closed down the

art department at MGM, all those paintings were taken by three guys, one guy

from MGM’s library and the other two were outsiders from a salvage company. These guys took them and they were trying to

sell them, they were going to build a museum for motion pictures. They took them… it irritated me. I wanted to get some of the others that I really

liked such as Mutiny on the Bounty. I’m

very sorry that I was so weak minded not thinking of these things and trying to

grab them. They wouldn’t let me take even

a brush out of that building! In the

meantime the salvage company came down and took down the whole place, and they

took those paintings and everything.

So much stuff was taken.

When Kerkorian finally closed down the

art department at MGM, all those paintings were taken by three guys, one guy

from MGM’s library and the other two were outsiders from a salvage company. These guys took them and they were trying to

sell them, they were going to build a museum for motion pictures. They took them… it irritated me. I wanted to get some of the others that I really

liked such as Mutiny on the Bounty. I’m

very sorry that I was so weak minded not thinking of these things and trying to

grab them. They wouldn’t let me take even

a brush out of that building! In the

meantime the salvage company came down and took down the whole place, and they

took those paintings and everything.

So much stuff was taken.  Greg Jein got two of those miniature Russian

Mig jets from Ice Station Zebra, and he was telling me what those guys were

taking… all the old illustrations and sketches were stored in one of the old

stages upstairs. Well, some of these

people found stuff and were lifting it.

People who didn’t even work on the lot got away with them. That was tragic. The only ones they didn’t get are the ones

that I saved to help me with other paintings.

We had pastels from the old days, and there was about 3000 of them. They kept everything on file. When people wanted to know what I did, they’d

show the steps that were shot before the black matte on it, and then the whole

drawing, and the partial painting, and the completed painting. They had hundreds of those things around. I remember the ones that thrilled me to death

from those Tarzan pictures.

Greg Jein got two of those miniature Russian

Mig jets from Ice Station Zebra, and he was telling me what those guys were

taking… all the old illustrations and sketches were stored in one of the old

stages upstairs. Well, some of these

people found stuff and were lifting it.

People who didn’t even work on the lot got away with them. That was tragic. The only ones they didn’t get are the ones

that I saved to help me with other paintings.

We had pastels from the old days, and there was about 3000 of them. They kept everything on file. When people wanted to know what I did, they’d

show the steps that were shot before the black matte on it, and then the whole

drawing, and the partial painting, and the completed painting. They had hundreds of those things around. I remember the ones that thrilled me to death

from those Tarzan pictures. |

| THE PRODIGAL (1955) |

|

| ATLANTIS - THE LOST CONTINENT (1960) |

I saved some like the Las Vegas casino painted ceiling mattes for an Elvis Presley picture and a bunch of others. I even managed to grab one of Albert Whitlock’s paintings of the Gemini rocket on the launch pad and I saved that, maybe from Howard Anderson’s company. Linwood Dunn had a garage full of mattes at one time, including a bunch of Albert’s Star Trek paintings. I think all of those were sold.

|

| A very rare DUEL IN THE SUN (1947) Cosgrove matte. |

|

| PLEASE DON'T EAT THE DAISIES (1960) - tilt down matte shot. |

HANDLE WITH CARE – GLASS MATTE MISHAPS:

|

| STRANGE BREW (1983) |

|

| YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN (1974) |

Another thing I was doing for a

commercial… it was about the size of a table top – a square or rectangle. I got the thing done and I wanted to do a

little more on it, so I was going to carry it out in the sun and I picked up

the painting and it just fell into 1000 pieces!

You’ve got to use real good glass, and it can’t be aged!

There was another one… on one of

the Peter Sellers things, one of the Pink Panther series, they didn’t like the

matte shots done in England and I had to redo some, and it’s always when you

think you’re done, and I think the paint has something to do with it, just a

little tap, and you snap it!

|

| KING OF KINGS (1961) |

THE YURICICH METHOD:

Let’s say there were some buildings

in the original dupe, and I start with one building and draw the line up, if I

wasn’t working on the enlargement already which had the building there. I’d work on that part, and I’d work another

part and it was the main structure of the shot, whereas if I were to do it now,

or in the last 25 years, I’d work on a building, but I’d paint that in real

quick, in paint – not draw it unless I had to be very precise. I’d go all the way across and that would give

me a feel when we shot a test as to where I was headed. If there was a sky, then I would make the

sky…I would get that in. That was my

‘key’ and I would paint some of the building and I would move over here so that

instead of working on one end and sweeping across, I would be jumping from one

to the other, and keeping everything in continuity so that one side wasn’t too

strong or a contrasty green and the other side a recurring red, or

whatever. You just keep doing it and it

keeps centering in, then you start picking from your tests the stuff that makes

it come alive. You’ve been doing it all

along, but now you’re gonna do the things that give it that sparkle and give it

the ‘life’.

Of course, everything is predicated on

what the dupe looks like. If it’s wrong,

I wipe it off and then do it again. I’ve

found that a lot of times I’m painting ‘mud’.

I have to paint and match to what I’m painting to. It’s the live action part. If it’s a dull colour, that’s what I paint

to. I had no problem with those

things. You had to have a feel for it

for that kind of work. I remember one

time, Henry got so carried away with a painting for Raintree

County that he fell in love with

the upper part of it. It actually looked

like two shots in one painting – one was set way forward and the other went way

back.

Of course, everything is predicated on

what the dupe looks like. If it’s wrong,

I wipe it off and then do it again. I’ve

found that a lot of times I’m painting ‘mud’.

I have to paint and match to what I’m painting to. It’s the live action part. If it’s a dull colour, that’s what I paint

to. I had no problem with those

things. You had to have a feel for it

for that kind of work. I remember one

time, Henry got so carried away with a painting for Raintree

County that he fell in love with

the upper part of it. It actually looked

like two shots in one painting – one was set way forward and the other went way

back. |

| One of the less noticeable matte shots from GHOSTBUSTERS (1984) |

PHOTO ENLARGEMENT MATTE SHOTS:

|

| THE WORLD, THE FLESH & THE DEVIL |

At the time (early 50’s) they often worked

on photographic enlargements and we’d paint directly onto that photo print to

make our matte shot . It could be a real

time saver. They would make an

enlargement of the scenes and they didn’t have to draw it out… I didn’t see why

anybody else didn’t do it. You didn’t

have to draw a damn thing… you just made a big black and white photo. The reason they kept me on was that when they

first started doing this, you had to glue photographic paper in a dark room

onto a large board and they would add Shellac.

You had to leave the Shellac exposed so that it would evaporate and then

you’d glue the photographic paper on and right next door is the darkroom where

the lab guys develop a print. This was

all on about a half inch thick plywood.

If the photo was too contrasty, when you painted on it, it would show

through… you had to get it just right.

That’s where I learned it…all that stuff in the paper comes right

through your paint. I don’t know how I

made tests with it.

|

| LOGAN'S RUN (1976) |

In several pictures we did an awful lot

of it. The World, The Flesh and the Devil with the three people left on earth

and everything is abandoned, so New York City has no traffic, buses overturned

– we used all real photographic enlargements of the library and stuff and have

to paste them down using this technique, and then paint the stuff to tie it in.

|

| WORLD, FLESH, DEVIL photo blow up matte technique. |

|

| One of the many wonderful expansive painted mattes from THE GREATEST STORY EVER TOLD (1966) |

CLARENCE SLIFER – OPTICAL GENIUS:

|

| Back row: Matt & Clarence |

When I started with Clarence, he

understood matte paintings and everything else.

When he developed his aerial image optical printer he had his machinist,

Oscar Jarosche, standing there, and as he thought of something that he wanted

built, he just told Oscar and he then built it for Clarence. I’m not that technically minded to follow the

physics of Clarence’s aerial image system… it’s a motion control sort of

thing.

When they were making this