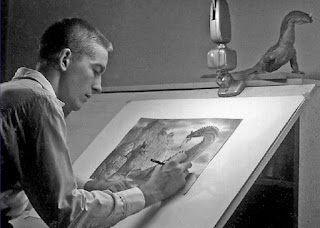

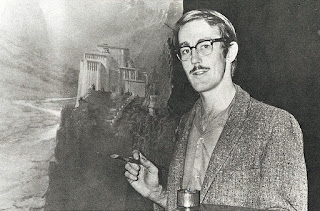

JIM DANFORTH: Matte art's last individualist

It’s with great pleasure that I present today’s NZ Pete

Visual Effects 'special edition'.

For decades fanzines, journals and books have dedicated a great

deal of effort – and rightfully so – in covering Jim Danforth’s iconic stop

motion animation work as well as the convoluted circumstances surrounding the

various un-realised features which Jim has tried so hard to get off the

ground. Regrettably, no article nor

author to date had attempted to cover Jim’s other, quite considerable area of

expertise – that being the highly skilled art of movie matte painting which has

occupied a significant portion of Jim’s time professionally for around four

decades. I suspect that most of Jim’s legions of fans possibly aren’t even

aware of the major contributions and vast output that Jim has undertaken in his

glass painting effects work. Today’s

article will reveal all.

The following conversations originated as just a few

isolated matte shot questions in the first instance and quickly developed into

a full blown career interview. It didn’t

take long before my overly inquisitive ‘nosey parker’ line of questioning would

be fulfilled by Jim’s comprehensive and detailed responses, where no cinematic

stone was left unturned.

Jim loves

the artform, probably even more that I do(!!), and loves to talk about not just his

own matte shots but those of industry veterans and even classic effects films

that we share a common respect for.

Jim’s enthusiasm was such that he “wrote off” at least one computer

keyboard in the process of typing up material for me! Now that’s dedication.

I want to thank Jim most sincerely for donating so much of

his time to furnish this author with so many answers to matte matters I’ve

always been curious about as well as many great anecdotes surrounding the personalities and politics of the movie business. Not only was

Jim generous with his time and knowledge, but also with diving into his

substantial archive of 35mm frame enlargements and behind the scenes photographs,

the great majority of which appear here for the first time anywhere.

A word too of thanks to Jim’s wife Karen, who not only assisted Jim on many effects shots over the years, but tolerated his spending so much time on line to a certain blogger in the South Pacific while his dinners got cold. Thanks are also due to David Stipes and Harry Walton for additional photographs and stories of "the good old days".

A word too of thanks to Jim’s wife Karen, who not only assisted Jim on many effects shots over the years, but tolerated his spending so much time on line to a certain blogger in the South Pacific while his dinners got cold. Thanks are also due to David Stipes and Harry Walton for additional photographs and stories of "the good old days".

Q: Firstly let

me say what a pleasure it is to interview you Jim. I’m most grateful for your time and

willingness to share your cinematic experiences.

Q: Firstly let

me say what a pleasure it is to interview you Jim. I’m most grateful for your time and

willingness to share your cinematic experiences.

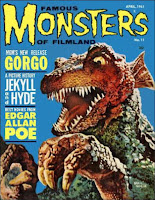

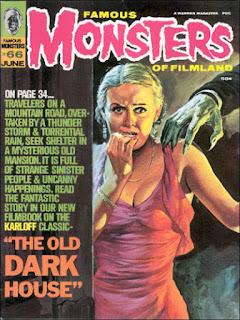

It goes without saying that I’ve been a huge fan for many

years, with probably old, well thumbed through issues of Forry Ackerman’s Famous Monsters of Filmland being the

initial exposure to your work as best I can recall, as it was for presumably

tens of thousands of like minded film buffs.

Just before I launch into a multitude of matte and effects questions

perhaps you’d like to comment on Forry and his huge influence on legions of not

only genre fans, but fully blown effects people such as yourself and many

others like Phil Tippett, David Allen and Dennis Muren?

JD: Forry

Ackerman was very influential for me and many others. He was, for a long time, the only

readily-available source of information about genre films and those who made

them.

Q: There really

wasn’t any other source for us sci-fi and monster hungry youngsters to find

info and behind the scenes pictures on visual and make up effects – even less

so far away in the South Pacific isolation of New

Zealand, I can tell you! It has always been with great regret that I

never visited The Acker-Mansion when

I had the chance on numerous visits to California. Of course it’s all gone now – dispersed to

the four winds.

Q: There really

wasn’t any other source for us sci-fi and monster hungry youngsters to find

info and behind the scenes pictures on visual and make up effects – even less

so far away in the South Pacific isolation of New

Zealand, I can tell you! It has always been with great regret that I

never visited The Acker-Mansion when

I had the chance on numerous visits to California. Of course it’s all gone now – dispersed to

the four winds.

JD: Yes, the

Ackermansion was… well, unique. Forry’s

collection began to be dispersed even while Forry was alive—sometimes without

his knowledge. I’d like to know where some

of his original Willis O’Brien art work is now (and a couple of my

contributions, too).

|

| Visiting the Ackermansion |

Tell us Jim, what sparked ‘the film bug’ in

you, and what was that first breakthrough movie which ‘lit the trick photography fuse’ as it were?

JD: The fuse had

been smoldering for a while with home-movie and stop-motion experiments begun

when I was twelve, but the explosion occurred

when I saw a reissue of KING KONG.

Q: It really couldn’t have been any other. A great many effects technicians, including very prominent figures such as Ray

Harryhausen found their inspiration (to

put it lightly) in the Cooper/Schoedsack masterpiece KING KONG, while many

of the next generation of effects people were seduced by Ray’s own films, most

notably THE 7th VOYAGE OF SINBAD and JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS, which

both seem to figure prominently in so many effects bios of guys like Bill

Taylor, Richard Edlund and Dennis Muren.

|

| A very early glass painting Jim made for his proposed version of 20'000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA. The glass here is positioned so that a real sky and clouds show through. |

JD: Yes, which stop-motion film was most

influential seems to be dependent on the age of the respondent at the time the

influence was first exerted. For me it

was KING KONG, but THE 7TH VOYAGE OF SINBAD also had a big impact on

me. I was already working in the film

business when I saw 7TH VOYAGE.

Q: Pioneers such

as John Fulton, Willis O’Brien, David Horsely, Percy Day, Fred Sersen, Emilio Ruiz del Rio

and Jack Cosgrove have entranced this author since I don’t know when. Any personal views on these, or any other

‘old style’ effects men Jim?

JD: When I was younger, the work of the

Lydecker brothers made a big impression… in addition to that of Willis O’Brien,

Mario Larrinaga, Ned Mann, and Peter Ellenshaw.

David “Stan” Horsely was the cinematographer on JACK THE GIANT KILLER, a

film on which I worked, but I didn’t have any direct contact with Mr. Horsely.

Q: Yes, Howard and Theodore Lydecker were in a class of their own. If I may, could I ask you your thoughts on successful trick shot design. What makes a good shot work? How do you ‘think’ out a prospective visual effect?

JD: Since my primary interest has always been

on making films with an emphasis on visual effects rather than effects just for

themselves, I usually think first about the arrangement of a sequence—particularly in the case of

stop-motion animation sequences—how the shots will be edited, what the tempo

is, and so on. But even with matte

shots, I tried to interject some of my own philosophy about sequence

design—tried but rarely succeeded. It

seems to me that having only one spectacular matte shot in a sequence calls

attention to itself in an undesirable way and could result in what Al Whitlock

referred to as “the JOHNNY TREMAIN

problem” —small live-action sets combined with spectacular painted

vistas. My view was that it would be

better to include one or two matte shots that weren’t spectacular—just enough

painting to suggest that, the sets or locations were larger than they actually

were. In that way the ‘big’ vista would

be less jarring.

|

| A practice matte Jim did in 1959 just for his own education—no attempt to composite it. |

Q: I’ve had many

industry people remark very positively about your VFX ‘shot design’ ethic.

JD: I have heard

a few of those comments—usually from other effects people rather than from

producers or directors.

Q: If I put a

few effects film titles to you, I would be interested to hear your professional

visual effects evaluation in a capsule:

THE INVISIBLE MAN…. IN OLD CHICAGO….

KING KONG…. GONE WITH THE WIND…. THIRTY SECONDS OVER TOKYO…. THE THIEF OF BAGHDAD….

QUO VADIS…. DARBY O’GILL AND THE LITTLE

PEOPLE…. THE BLACK SCORPION…. 20’000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA …. GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD…. COLOSSUS – THE FORBIN PROJECT….. BLADERUNNER.

JD: Please keep in mind that my judgements tend

to be harsh.

THE INVISIBLE MAN: Crude but effective—crude when compared

to the very subtle effects in DEATH TAKES A HOLIDAY,

made at about the same time.

IN OLD CHICAGO:

one of the very best ‘disaster’ films—along with THE RAINS CAME.. Beautifully integrated effects.

KING KONG: Ground-breaking despite some obvious effects

flaws. A triumph of shot design over

some technical limitations. Later

refinements did not result in similar films with as much impact and artistry as

KONG.

THIRTY SECONDS OVER TOKYO: Very well done, all around.

GWTW: Highly variable matte

paintings, that result in an overwhelmingly wonderful cumulative effect—one of my favorite films. Nice design work by William Cameron Menzies.

THE THIEF OF BAGDAD: Poetic, with

utterly superb matte paintings and hanging miniature shots, plus the first-ever

three-color traveling matte work (which permitted the story to be told, despite

some technical flaws.)

QUO VADIS: Spectacular, in all departments—superior matte

paintings and traveling mattes.

DARBY O’GILL: The

best mixed-scale effects I’ve seen, plus beautiful matte paintings and real solarization effects.

20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA: In

my opinion, the best-designed miniature ship scenes ever. Great integration of painted tank backings

and glass and matte art. The Nautilus

lying in wait for the nitrate ship at sunset is unforgettable. But what else would one expect with Peter

Ellenshaw and Ralph Hammeras collaborating—plus Harper Goff’s design of the Nautilus.

THE BLACK SCORPION: A great example of how to create mood

with a restricted effects budget. If

only the ants in THEM had been as exciting as those scorpions.

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS: highly variable effects, with some lacking in

subtlety—the burning bush being an exception.

The excellent designs may have been beyond the capabilities of the time,

although I think if Gordon Jennings had done the effects (as was planned), I

would have liked the results better.

THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD: Disappointing, although the

choreography of Kali is very well done.

COLOSSUS-THE FORBIN PROJECT: A very intelligent film.

Whitlock’s daring original-negative computer start-up shot is famous in the

world of matte paintings.

BLADERUNNER: Not a film I liked, although the matte work is

excellently done.

I think the art direction and the

paintings totally achieved the desired effect.

It’s just not an effect I happen to like.

Peter Jackson’s KING KONG: I can think of nothing good to say about that

film, except that I liked the introductory shots of New York.

Q: Well, that was interesting.

Most of those I’d have similar thoughts, though I loved GOLDEN VOYAGE

myself – a light year ahead of the very poor final Sinbad picture EYE OF THE

TIGER, which followed it. I actually really liked the latest KONG and

thought Andy Serkis made an amazing and unique contribution to this and the

recent Planet of the Apes picture.

There are many articles and interviews over the years with

you Jim where the key area of interest has centered on your stop motion

animation projects, yet very few

journals (if any) have covered your quite substantial matte painting

career. I’d like to kick this off with

the question I’d like to present to all matte painters: if you’re able to recall, which was the

glass painted shot which made that impact and triggered off that ‘love’ of the

artform for you? (film/shot?)

There are many articles and interviews over the years with

you Jim where the key area of interest has centered on your stop motion

animation projects, yet very few

journals (if any) have covered your quite substantial matte painting

career. I’d like to kick this off with

the question I’d like to present to all matte painters: if you’re able to recall, which was the

glass painted shot which made that impact and triggered off that ‘love’ of the

artform for you? (film/shot?)

JD: First, I

think I should point out that my animation work got more attention than my

matte work because animation is part of the story,

which is what most people are interested in.

Secondly, animation calls attention to itself because it is inherently

‘phoney’ of theatrical. A well-done

matte painting recedes into the background, although mattes can be very

memorable and evocative.

|

| Monoclonius drawing is from Jim's production TIMEGATE. The film was not finished. Drawn in graphite and reproduced as a brown-line print for presentation. |

But, to answer your question, I suppose it would be KING KONG and the

arrival at Skull Island

shot. The setting is almost a character

in that film and was created largely by glass art. Of course, when I first saw it, I had no idea

how it was done.

Q: Oh yeah, that shot is iconic, though I thought the similar

establishing glass shot in SON OF KONG to be even better both in terms of

composition and a far cleaner composite.

I just loved the Orville Goldner animated birds doubled into the former

shot.

I absolutely adore the matte painted effects shots from The Golden Era, with probably late

twenties through to late forties encompassing the artform at it’s most

essential and‘magical’… the proverbial Dream

Factory. The use of the matte

process was at it’s peak, with vast visual effects departments and large

numbers of artists turning out hundreds of mattes per year. Would you have liked to been a part of that

era Jim where the painted matte was so extensively used and highly valued?

JD: No.

Q: You are

generally acknowledged as one of the effects industry’s most ‘individualistic’

visual effects creators from my understanding, so would you feel comfortable as

part of a large stable of matte painters, such as the Warren Newcombe unit at

MGM or Ray Kellogg’s team over at Fox for example?

JD: No.

Q: From my

research, Walter Percy Day, England’s

most eminent matte painter based at

Denham Studios, would control each and every step of the process for his stable

of painters where they were required to paint only as expressly directed

by the master with no room for individuality.

It was almost a ‘paint by Pop’s

numbers or not at all’ scenario it

seems.

JD: I suppose the idea was to get the Walter Percy

Day look that the customer was paying for, and only Pop Day knew how to get

it—or thought so.

Q: There’s no

disputing Poppa Day was the master in

my book, with a phenomenal catalogue of glass shots over a very long period,

with much of his best work in the silent French cinema. I lost count of how many ornate ceilings and

ballrooms Day must have painted.

JD: I wish I knew more about Day’s entire

career. I really, really like the work

he did for Korda and on BLACK NARCISSUS, but some of his later work, such as

THE BLACK ROSE is, in my opinion, not very good.

|

| Jim at work on a foreground painted matte on hardboard for EQUINOX. Jim says he wasn't too happy with this painting, but again, it looks great to me and I'd happily own it. |

Q: I’m

interested in your thoughts regarding the various Golden Era matte departments’

styles and technical methods?

JD: I think there was a certain amount of “not

invented here” in effect during those years—meaning that methods used effectively at one studio might be

shunned by another. In part that was due

to the type of equipment in which a studio had invested. In part it was due to the preferences of

whoever was in charge of the matte department at a particular studio (which, of

course, influenced the equipment that was constructed).

Clarence Slifer at MGM refused to believe that Al Whitlock

did most of his mattes on the original negative, so Matt Yuricich phoned Al and

put Clarence on the phone. Al explained

to Clarence how he did his shots. After

the conversation ended, Clarence turned to Matt and said “Well, maybe he does and maybe he doesn’t.” What was an everyday procedure for Whitlock was inconceivable for

Slifer, even though Slifer had used the same procedures in earlier times. Sometimes one can ‘brainwash’ oneself.

My understanding is that Jack Warner liked clouds in the

matte shots of his fims, so that was an influence from outside the matte

department. Also, I was told that at

Warner's it was common to use matte paintings to improve the apparent focus on

the foregrounds of miniature sets. When

shots of miniature trains had out-of-focus foregrounds, the foregrounds were

matted out and replaced with sharp, painted versions of the miniature.

The quality of mattes sometimes changed within a studio as

the department head changed. I thought

the mattes done at MGM during the period when Lee Le Blanc was in charge were

not as ‘artful’ as those done by the Newcombe department.

At Fox (and at Film Effects of Hollywood), precision-machined

aluminum grommets were pressed into holes drilled in the hardboard panels on

which the mattes were painted. The holes

in the grommets fit over pegs on the photographic easels. At Universal, Al Whitlock simply slid his

paintings into a channel on the matte stand and pushed them until the wood

frames encountered a ‘stop’ on the matte-stand frame. When Al did dupe composites, he used the

un-illuminated opaque painting on glass as a hold-out matte when duping the

live action from separations while photographing a brightly-lit white

background positioned behind the painting.

Then the painting was illuminated and photographed over a black

background to double expose it onto the film with the live-action dupe. The painting and the ‘matte’ fit

perfectly. At Fox, registration

pegs were necessary because the board with the painting was not the same board

used to dupe the live action. A duping

board was created by placing the board with the painting on a tracing table

with identical registration pegs, then lowering an aluminum frame, to which had

been taped a large sheet of translucent plastic tracing ‘vellum’, then tracing

the matte line from the painting board onto the vellum. The painting board was then removed. A new board, painted pure white and fitted

with the same type of grommets, was the placed in registration on the tracing

table, and the matte line position was transferred onto the duping board. The duping board was then painted gloss black

in the area corresponding to the area to be occupied by the painting. The painting board was painted gloss black in

the area to be occupied by the live action.

The visibility of the matte line was dependent on the accuracy of the

tracing, transfer, and blacking in. Which system do you think was faster, the

Universal system or the Fox?

At Fox (and at Film Effects of Hollywood), precision-machined

aluminum grommets were pressed into holes drilled in the hardboard panels on

which the mattes were painted. The holes

in the grommets fit over pegs on the photographic easels. At Universal, Al Whitlock simply slid his

paintings into a channel on the matte stand and pushed them until the wood

frames encountered a ‘stop’ on the matte-stand frame. When Al did dupe composites, he used the

un-illuminated opaque painting on glass as a hold-out matte when duping the

live action from separations while photographing a brightly-lit white

background positioned behind the painting.

Then the painting was illuminated and photographed over a black

background to double expose it onto the film with the live-action dupe. The painting and the ‘matte’ fit

perfectly. At Fox, registration

pegs were necessary because the board with the painting was not the same board

used to dupe the live action. A duping

board was created by placing the board with the painting on a tracing table

with identical registration pegs, then lowering an aluminum frame, to which had

been taped a large sheet of translucent plastic tracing ‘vellum’, then tracing

the matte line from the painting board onto the vellum. The painting board was then removed. A new board, painted pure white and fitted

with the same type of grommets, was the placed in registration on the tracing

table, and the matte line position was transferred onto the duping board. The duping board was then painted gloss black

in the area corresponding to the area to be occupied by the painting. The painting board was painted gloss black in

the area to be occupied by the live action.

The visibility of the matte line was dependent on the accuracy of the

tracing, transfer, and blacking in. Which system do you think was faster, the

Universal system or the Fox?

RKO may have had the most versatile matte department, in the

sense that they used different methods for the composites, depending on the

requirements. Linn Dunn told me that at

RKO they had one artist who specialized in doing the blends for all the

paintings. As I recall, that artist was

Paul Detlefsen (who later painted fine-art illustrations in a neo-Currier &

Ives style).

Many of the mattes at RKO were put together using the same

rear projection process patented by Willis O’Brien in 1928 (granted 1932).

Disney utilized the ‘O’ Brien’ projection method for most of

the matte shots done at the Burbank studio by Peter Ellenshaw (with equipment

modified and/or engineered by Ub Iwerks) up until they switched to projecting

separations (around the time that Alan Maley took charge of the department, I

think) But that was well past the

‘Golden Age’.

Q: Some studios

seemed to hold the high ground, with Metro Goldwyn Mayer’s enormous resourses

no doubt a prime factor in the quality of the output from Newcombe’s matte

department. Fox and Warners both had

huge effects staff, with the latter employing some eight painters at their

peak. Universal on the other hand, by

all accounts had a tiny matte department as far as I know, with just the one

painter, Russell Lawson, for several decades.

Some of there large matte shows must have surely seen additional

painters brought on board to turn out the number of mattes required, and I’m

thinking here of Hitchcock’s wonderful and exciting SABOTEUR – a huge matte

shot show. I heard somewhere that well

known Art Director John DeCuir may have painted mattes on that film with

Lawsen?

JD: I really don’t know anything about the mattes

on SABOTEUR. I thought they were

variable in quality. I remember the

Statue of Liberty mattes as being very good.

Q: There

were an awful lot of mattes in that show, some really invisible such as the

stuff with the ship at the docks as well as several ceilings. Could you tell us a little about your own earliest

experiments in glass painting Jim?

|

| An early glass painting by Jim for a non-professional version of 20'000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA. Even at a young age the skill is readily apparent, as is the drive. |

JD: When I was

about fourteen or fifteen, I started

painting ‘tests’ for my own amusement and education. Originally, I used water-soluable tempera

paint (poster paint), because I didn’t know any better. After the paint dried, it tended to flake off

the glass. I did some glass paintings

for an amateur version of 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA that my friends and I

worked on for many months but abandoned before any ‘principal’ photography was

done. Then I did a painting on bristol

board to be used as an establishing shot for a 16mm version of THE PIT AND THE

PENDULUM (this was several years before Roger Corman made his film). I based the layout on the famous painting “Toledo in a Storm” by El Greco. Holes were cut in the bristol board so I

could backlight the windows of the buildings.

(This was before Al Whitlock taught me that was unnecessary—that if one

painted in the correct key, painted lights would photograph bright

enough.) I abandoned PIT for a more

interesting idea: GERALDINE IN JEOPARDY—a humorous 16mm silent serial set in

the time of the American Civil War. For

that project, I painted a house on glass and also tents and a canon and a watch

tower for a scene of General Grant’s camp.

The house shot was filmed in a local park, with ‘Geraldine’ running

toward the non-existent house, but the glass of General Grant’s camp fell over

and broke while we were setting up on location.

Then I did a “Hall” hardboard shot of a jungle setting which

I photographed in 35mm with me moving

cautiously toward the jungle area. This

was for a test involving a phororhacos.

|

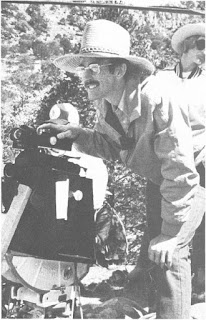

| Jim and Karen and part of the crew at Snowbird, Utah, filming the plate for a matte shot for John Carpenter's MEMOIRS OF AN INVISIBLE MAN. Ted Rae was the cameraman. That's his camera. |

Q: Was there

ever a time where you saw yourself as becoming purely a studio matte artist or were your cinematic interests far too varied

to allow you to settle into just one creative slot?

JD: I didn’t want to do visual effects; I wanted

to make films (with visual effects). Visual

effects—particularly stop-motion effects—seemed to be the entry-level job most

related to general filmmaking.

Q: I’m very

interested in your early ‘cold call’ encounter with Disney matte department

head Peter Ellenshaw? That must have been one unforgettable

experience?

JD: Absolutely right. I’ve described that experience in my

memoir. The three things that impressed

me the most were: A) the realistic effect

of Peter Ellenshaw’s paintings compared to their very loose style on close

examination. B) Ellenshaw the man—very gracious and charismatic. C) The clarity

of the rear-projected 8-perf. (VistaVision) images used in Ellenshaw’s

department for compositing most of the mattes.

Q: How many

painters and cameramen did Ellenshaw have with him at that time?

JD: In addition

to Ellenshaw, the only other artist I saw was Al Whitlock, although I

understand from your blogs that Jim Fetherolf may also have been at Disney

during that time. Peter also introduced me to an assistant who worked in the

room where the paintings were photographed.

I don’t remember his name.

Ellenshaw mentioned that the man had worked on KING KONG.

Q: Was there

ever the possibility of you taking up a matte painting position in Peter’s

department? Would you have done so had the

invitation been forthcoming?

JD: It was never mentioned, and I never thought

about it. Remember I was VERY inept at

that time. I was nineteen. I suppose that if the opportunity had

presented itself a few years later I would have jumped at the chance.

Q: Peter’s son

Harrison told me recently of an occasion in 1964 in which he temporarily worked

as an intern in his father’s department and he got to know artist Jim

Fetherolf. Jim was, according to

Harrison, an excellent artist, but sometimes very frustrated working at

Disney. Fetherolf would say: “I don’t know why I even bother to do this,

as Peter will just walk in later and change it all with a big brush and make it

better”. As I understand the

situation, Albert Whitlock had similar issues and wanted to break free.

|

| Peter Ellenshaw |

Q: Harrison

also mentioned to me that although various artists painted the shots on Disney

pictures, there were probably few instances where the painting left the easel without

Peter having dabbled away upon it with his brush or changed things. How would this sit with the average artist I

wonder?

JD: Well with a fine-art painter, not well, but

matte painting was more of a craft than an art, in some ways, so many junior

artists probably accepted it.

Q: Would I be

correct in suggesting that the Disney effects operation was very much a tightly

run factory with a regimented and

conservative structure with the accent on ‘pure painting’ and nothing more for

the artists?

|

| Albert Whitlock |

Q: I’ve heard

that some Disney artists were also frustrated at the embargo imposed on trying

new gags and styles, such as Alan Maley wanting to experiment with Front

Projection for compositing and Al Whitlock wanting to develop his split screen

moving sky animation, which of course he mastered once he moved over to

Universal.

JD: I don’t know

about Alan Maley’s frustration. Possibly

the reluctance to change was due to the investment in time and money that had

been put into developing the VistaVision rear-projection

and masking system, which I understand was perfected by Ub Iwerks. Personally, I’d choose rear projection over

front projection for a matte painting situation.

Q: Were Disney

still using oils to paint or was all of the matte work being painted with

acrylics by this time?

JD: In 1959, when I visited Ellenshaw, the

paintings were done in oils. As I

recall, acrylic paints for artists didn’t make an appearance until several

years later.

|

| Jim Danforth and Tom Corlett painting a convention hall full of refrigerators for a projection pull-back shot as part of a Cascade TV commercial |

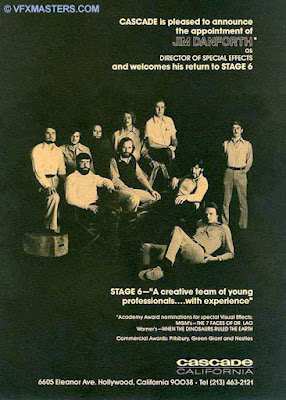

Q: You have had

a long association with Gene Warren, Wah Chang and Tim Baar and their effects

house Project Unlimited. At a time where

effects units were primarily big studio based departments with a considerable

chain of command and power politics, was an independent operation like Project

Unlimited seen as an oasis of creative freedom in what was then a very ‘front

office and mogul’ run industry?

JD: I suppose so,

but then I’d had no experience at that time with the “mogul-run” industry. Later, Project Unlimited did seem to have

more freedom, particularly since the restrictive union policies of the major

studios were not rigorously applied, even though Project was a union signatory

shop and we all belonged to the IATSE.

Q: Could you

tell us about your role at Project Unlimited.

I understand you were involved with assisting Gene Warren on some of the

special effects shots for one of my favourite films THE TIME MACHINE?

JD: I didn’t assist Gene, except in the sense that

all the employees assisted him to get the jobs completed. Gene only rarely did any hands-on work by the

time I started at Project Unlimited. I

did assist Bill Brace with some lighting manipulations during the TIME MACHINE,

but I didn’t do any painting (except for a black matte with which I assisted

Wah Chang).

Q: Would you

like to describe the facilities and equipment at PU? Were they set up for all aspects of optical

cinematography for example or were such shots farmed out elsewhere?

JD: Project

Unlimited could do NO optical effects when I started. They were primarily a prop-making shop and

stop-motion facility. At first, all the

optical work was farmed out to optical companies or sent back to the optical

department of the studio making the film.

|

| A Bill Brace matte from THE TIME MACHINE. |

JD: What went wrong was Project not having any

compositing facilities, nor a

thorough understanding of how to approach compositing. That may sound like a judgemental view from a

nineteen-year-old, but I had spent hours in the AMPAS library and other libraries, making a careful study of

effects techniques.

Bill’s paintings that were intended to be composited with

live action were painted on black and white photo enlargements. They were photographed just as they looked,

with the black and white photo visible.

The film of the painting was delivered to The Howard Anderson Company

where a film matte was created to block out the live-action area. A negative print of this matte was use to

block out the area of the live action into which the painting would be

inserted. There was no way for Bill to

blend his painting to the live-action photography. All join lines had to be hard-edged. Because of the nature of the shots, I don’t

think it was necessary for Bill to make any composite tests. All the color balancing and matte fitting was

done on the optical printer.

|

| TIME MACHINE split screen. |

Q: What method

did PU favour for their matte composite photography?

JD: Having someone else do it…until I convinced

them otherwise for THAT FUNNY FEELING.

|

| The destruction of London from THE TIME MACHINE |

JD: I agree. Those scenes were finished before I arrived,

but then they wouldn’t have listened to me anyway.

Q: The Academy

oddly didn’t seem to mind – though I’ve had so many problems with strange AMPAS decisions over the years I suppose

it doesn’t surprise me. It’s still a

great little film though.

JD: It’s a film that didn’t capture the feeling or mood of the

Well’s novella, but it became a nice film on it’s own, as did 7 FACES OF DR LAO.

Q: I understand

that Bill Brace did most of the matte painting for PU, with former Roy

Seawright matte artist Luis McManus painting on some projects. Did you ever undertake any matte painting

during your time at PU?

JD: Luis McManus did some paintings for JACK

THE GIANT KILLER, but he did them for The Howard Anderson Company, as did Al

Whitlock (who did three paintings that I can remember).

|

| JACK, THE GIANT KILLER unused shot |

Later, I convinced Gene Warren to let me do an original

negative composite shot for THAT FUNNY FEELING.

I did the small amount of painting required by that shot.

Q: I understand

that Gene Warren had some background in matte painting, or to be more precise, matte ‘blending’ -

having been taught the ropes by the once legendary Jack Cosgrove while

working for Jack Rabin and Irving Block on zero budget pictures in the 50’s

such as MONSTER FROM THE GREEN HELL.

JD: I never

heard so much as a whisper about that.

As far as I know, all the Rabin-Block mattes were painted by Irving

Block. Gene never revealed any interest

in, or knowledge of, matte painting. He

was primarily an animator—a very good one.

Q: Yes, Gene did some nice work in Tom Thumb as I recall. Project Unlimited were constantly in demand

throughout the 1960’s. Were they

perceived as being a sort of “ILM” of

the day who weren’t afraid to tackle new and innovative effects that may have

been outside of the sphere of the more traditional big studio visual effects

departments?

JD: Perhaps.

The studios didn’t get involved in stop-motion animation much, so

Project got a lot of jobs that required stop motion. Wah had a good reputation as a costume

fabricator, so Project got jobs for Las Vegas

shows as well as for film creatures.

Project made dummies for SPARTACUS, Shields for THE WARLORD, and

costumes items for CLEOPATRA. However,

Project Unlimited didn’t do composite work, at least not initially. The really big effects work was done at the

major studios, as when Buddy Gillespie filmed the submarine shots for ATLANTIS,

THE LOST CONTINENT in the tank at MGM.

MGM also handled the matte paintings for ATLANTIS. Project did only a

few animation shots for that film..

|

| A staff portrait of Project Unlimited - sans Jim. Photo from Jim's 2011 memoir 'Dinosaurs, Dragons and Drama' |

Q: With so many

studios closing down their special effects departments in the early sixties I

guess there were a lot of matte artists seeking work. The competition for freelance assignments

must have been great?

JD: I wasn’t aware of any of that because I

wasn’t trying to compete as a matte artist.

The matte artist’s union kept

refusing to let me join, so, whenever an opportunity arose to paint a matte, I

just went ahead and did it secretly.

Q: So was the cave shot that was deleted from JACK THE GIANT

KILLER your own first professional glass shot?

JD: Yes. Of those

that actually made it up

onto the screen, THAT FUNNY FEELING was my first.

|

| Gigantipoids was a pre-production illustration for the last feature film that Jim contemplated, titled KRANGOA. (the family of ape-like creatures) |

Q: In your own

matte art are you an oil painter or an advocate of acrylics?

JD: Originally, I

painted all my professional mattes in oils.

About 1975, I developed some sort of allergic reaction to the paint

chemistry and had to change over to acrylics.

That required a completely different technique and a re-learning

process.

With oils, I blended skies by using cloth or polyurethane

pads to pat the color after it had been brushed on in bold strokes. With acrylics, I found I needed to use a

spray gun, with cross-hatching or stippling in some areas. My acrylic paintings (viewed in person) never

had the impressionistic looseness of my oil paintings, but they photographed

satisfactorily in most cases.

I’m now back to painting in oils without turpentine and

without cobalt drier. So far, no allergy problems, of course, I’m now painting ‘fine art’ not mattes.

Q: Take us

through the typical time frame of the average glass painting Jim. How do you begin? Do you project a 35mm frame onto the

pre-primed glass and trace from original first unit photography or do you

approach it differently? Are there dip

tests of short lengths of test negative and so forth? How many tests are on average required until

a final acceptable match?

JD: There are many variables. First, only a few of my matte paintings have

been done as latent-image composites.

For those, I usually projected a developed film clip to trace off the

blend-line position. If architecture

needed to cross the matte line, those features were also traced.

Tests were made each day as the work on the painting

progressed. Sometimes hand-developed

dip-tests were made during the day to speed things up (but those produce only a

monochromatic image). The number of

tests varied. Usually, I could get a

blend with four to six tests, but some jobs were problematic. I think I did about twenty tests for the

MEMOIRS OF AN INVISIBLE MAN beach-house shot, because the lab was having

problems and kept shifting my jobs to different printers. That caused major shifts in the overall color

and made it difficult to evaluate the basic lay-in as to sky color. Then the editor wanted changes, and so on.

|

| The original matte painting for the above shot. |

Sometimes, I painted on dark

“greylight” glass. This enabled me to

put the process screen in contact with the back of the matte glass, so that

there was virtually no parallax between matte glass and projected image. The light illuminating the painting was

reduced in intensity as it passed through the glass and was reduced in

intensity again when the resulting ‘fog’ on the screen bounced back toward the

camera.

But the image from the rear

projector was reduced only once on its way to the camera. Furthermore, the light on the painting went

through the glass at an angle, making the light path for the ‘fogging’ light

longer than for the rear-projected image, with the result that the glass had

greater dark density for the front lights than for the rear-projected image.

Once proper filtration had been

established for the system, the paintings could usually be balanced by eye, but

some critical matches required film tests.

I did one two-projector composite

with very little painting over one weekend, after an initial wedge test.

Q: I’ve always

been of the belief that a successful matte shot can only be as good as the

cinematographer shooting the plate and tying the composite together. Is that too simplified a statement do you

think?

|

| Hilltop monastery painting for the action film NINJA III |

It’s really not the job of the

camera person to ‘tie the shot together’.

The matte artist is responsible for the marry-up. In most cases, the camera person is

responsible for only the dupe and maintaining it’s consistency (unless one is

foolish enough to be making the composites on an optical printer by using

filmed black mattes and counter mattes).

I agree that the success of a shot may depend in large part

on the original photography. I have had

to do some very ingenious ‘corrective’ printing to rescue live-action

photography that was underexposed by the cameramen—even very good directors of

photography. I was able to do this on

one occasion by bi-packing a ‘plus-density’ mask that restored shadow density

on a shot that had been underexposed.

That may seem backwards, because “underexposure” sounds as though it

would make the shadow areas darker. Film has a limited density. When a scene is underexposed, The highlights

and mid tones get darker, but the ‘blacks’ don’t, When the mid-tones and highlights get

corrected back to a normal density, the ‘blacks’ become grays and require

additional density to be added synthetically.

On another occasion, I had to print the projection plate

with a special traveling matte that lightened only the underlit actors in the

foreground. In a similar case, I had to

use a traveling matte to enable me to print the characters in shadow at one

exposure and the meadow behind them (in sunlight) at an exposure that brought

the two portions of the scene into a better balance. All that must

happen before the painting can be started. If the artist doesn’t get these problems

ironed out at the start, the artist can sometimes end up “Chasing the Dupe”—a phrase I first heard from Matt Yuricich.

|

| An FX shot from the 'Hard Water' episode of the tv show SALVAGE 1 with painted iceberg and Whitlock inspired 'slit gag' effects for the approaching missiles. |

JD: I would always bow to Matt’s superior experience, but as it happens, I agree with him completely.

Q: I think

you’ve tried to shoot as many of your own mattes personally. Is that right?

JD: Yes, for the

reasons I just stated. Plus, some of my

procedures involved animation at the time the painting was being filmed. It’s also less expensive.

|

| A 16mm latent-image matte painted comp from Jim's THE PRINCESS AND THE GOBLIN reel. |

Q: Tell us how

you met and became longtime friends with Albert Whitlock?

JD: I met Al in 1959 when I visited Peter

Ellenshaw at Disney studios. Al was at

work on a house painting for POLLYANNA, which I think was a latent-image shot.

I ran into Al again several times when he was painting for

JACK THE GIANT KILLER at The Howard Anderson Company.

|

| Painting a foreground glass for PAUL BUNYAN |

That job lasted only about a month, because Al got into a conflict with the Universal management about how to charge off my salary (Al was afraid that if my salary was charged against his matte shots—of which I was not yet painting any—he might lose out on jobs). But Universal kept me on the payroll and shifted me to another part of the art department. Al and I remained on good terms, and we began to discuss a project that each of us had been intrigued by independently: THE LOST WORLD.

In addition to staying in touch with Al and having dinner

with him and his wife on numerous occasions, I worked for Al again during I’D

RATHER BE RICH (stop-motion animation of shoes) and, years later, when he was

at work on DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER and was also doing matte shots for the GUNSMOKE

TV series.

Al recommended me for several of the jobs I did over the

years.

Q: I’d

love to have seen that Danforth-Whitlock LOST WORLD.

JD: I thought I would

too. However, as the years passed, Al

realized that the dinosaurs would inherently be more memorable than the matte

paintings, so he took over the creation of the dinosaurs, and I was out.

|

| Another PRINCESS AND THE GOBLIN matte shot. |

JD: The independent houses usually had a way to photograph the paintings, and a matte artist doesn’t take up much space. I think Al painted at home on the Butler-Glouner jobs and on some of the Howard Anderson jobs. But, on occasion, Al painted at Howard Anderson’s facility on the old RKO lot in Hollywood.

Q: I think many

of those Poe films from American International such

as PIT AND THE PENDULUM and I think COMEDY OF TERRORS used Al’s talents

to great effect. I’ve often wondered too

about another Butler-Glouner show THE DEVIL AT 4 O’CLOCK which has several

mattes that look very much like Albert’s.

JD: I never asked

about THE DEVIL AT 4 O’CLOCK.

Q: Terrible

blue screen work with Spencer Tracy’s silvery hair becoming totally transparent

at times due to blue spill or problems pulling the mattes. Great Larry Butler miniatures though and some

pretty bold epic composites shots for the time.

JD: The miniature volcano was built in large scale on Butler’s ranch. It’s been

said that Larry wanted a lake on his property, and dredging out the dirt to

build the volcano was a good head start.

Q: I’m very

interested in one particular project you undertook, THAT FUNNY FEELING, which

although a Universal film with photographic effects by Al Whitlock, your own

contribution was through Project Unlimited as I understand it. The opening LA freeway traffic jam effects

shot was a stroke of genius Jim, not just in the wonderful stop motion, but

also in the precisely calculated camera elevation

done back at Project Unlimited on the miniatures as well as the flawless

blending of live action freeway against your impeccably lit and photographed

miniature set. One of your best effects

shots ever. Would you like to

tell us about that?

JD: I was

actually involved with two shots for THAT FUNNY FEELING—the head-on train

crash, for which I painted a large sky backing and the traffic-jam shot you

mentioned. My main contribution to the traffic-jam shot was

to steer Project Unlimited away from their plan of turning the element over to

some optical department to composite (no more giant matte lines, thank

you). I composed the shot, placed the

black matte in front of the live-action camera, and did the minimal painting

and the primary animation. Other

animators handled the background cars. Ralph Rodine did the lighting and camera

work. We

looked through a film clip of the live-action scene that was placed in the

movement of the animation camera, then moved the miniature set and the camera

around until it matched the perspective of the real freeway lanes. When the

shot was finished, Gene Warren took it to Universal, where they spliced it into

a loop and screened it over and over, pondering how it had been done. Not bad for my first professional

latent-image composite.

|

| The miniature head on train collision by Project Unlimited from THAT FUNNY FEELING with Jim supplying the painted sky backing. |

Q: Not bad!……it was technically and

artistically as good as it gets Jim.

Definitely one for the showreel and to be proud of. Unfortunately I don’t know anyone who’s ever

seen the film aside from me?

JD: Well, of course I went to see it. It was exciting to realize that, right in the

opening sequence with the trains and the cars, there was also a great Al

Whitlock painting of a New

York Street. My work was in good company.

Q: As

photographic effects supervisor, was Albert in any way involved in the design

or ‘look’ of that shot, or was it totally sub contracted?

JD: No, Al was

not involved at all, except for the fact that I had recently worked with Al and

felt comfortable about doing original negative work.

Q: You secured a

short term apprenticeship in Whitlock’s matte department around 1965, which I

imagine was an eye opening experience for you?

Can you share with us some of the effects work Al and his team were

working on at the time?

JD: As I recall, it was in 1964. MARNIE was in work at that time. I think SHIP OF FOOLS followed soon

after. THE WARLORD was on the planning boards in the art

department, but no filming had been done and Al hadn’t started on the mattes

yet. I

visited Al during the time he was working on mattes for THE WARLORD.

|

| From THE HIT MAN, a TV movie and pilot for Columbia. Danforth added scintillating light patterns in the glass columns. It's all painted except the trapezoidal room and walkway. |

Q: I’ve heard

that one of Al’s mattes around the time you were there, the one of the ship

docked with city background for MARNIE was really

disliked by the head honcho’s at Universal for some reason and they requested Al pull those shots from his showreel. Can you elaborate?

JD: Yes,

apparently there was a general dislike of that shot (and all the matte shots

from MARNIE). I thought it was a

particularly nice shot except for the improbable ‘God’s viewpoint’, which

Hitchcock seemed to use in several films.

(What is the camera supposed

to be supported by?) I think the real

problem was with a dreadful ship cut-out in a forced perspective set used for

lower angles. Perhaps viewer complaints

about a dreadful ship shot were not interpreted correctly. If I owned that Whitlock painting, I’d

proudly hang it on my wall. The effect of afternoon light was beautiful.

Also for MARNIE Al painted the interior of a tithe-barn stable with a bright glare of light

coming in the window. The glare was very impressive. It was just a thick streak of pure white

paint). The specific shot Al was primarily

working on when I arrived showed Sean Connery and Tippi Hedron walking to the

barn. Al pointed out that the shake roof

of the barn was created by alternating lines

of reddish and greenish shades of gray.

Q: That

barn interior tends to slip by totally unnoticed. The thing looks like almost all of it’s Al’s

paint excepting the actors and horse?

Can you recall it?

JD: My memory is that the painting showed the entire interior of

the vaulted, beamed ceiling, plus the top third or so of the support columns. My guess is that there was action filmed in

the foreground of the set—later edited out—and which required more of the

interior to have been constructed than would have been necessary for the shot

as it was finally edited.

Q: According to

Bill Taylor quite the opposite occurred with COLOSSUS-THE FORBIN PROJECT where

the studio brass were over the moon with that amazing ‘super computer boot up’

matte set piece and were keen to show it off.

Apparently that was Al’s most difficult shot from what Rolf Giesen told

me. I think it’s one of his best – and

all on original negative too!

JD: Yes, very impressive. Al said that he

missed the precise timing from his stop watch by about eight frames. That’s so close that no one would notice the

‘error’.

|

| Whitlock's 95% oils / 5% real COLOSSUS matte shot |

Q: I

have a before and after on that matte shot.

The amount of paint is remarkable.

It must have been something like 95% Whitlock and 5% genuine set! I think that must have been something Al

possibly picked up from Peter at Disney – not to get fiddly with demarcations

and preserving most of the ‘real’ set – just paint the whole damned

thing, which Ellenshaw was a genius at.

So many of his Disney shots were ALL paint –right around into the

immediate foreground with incredibly courageous brushmanship. Peter would just ‘slot’ in the actors somewhere

amid all that oil paint, and to beautiful effect. Things like DAVY CROCKETT and JOHNNY TREMAIN

are wonderful examples of this “ballsy” approach which most wouldn’t have the

guts to tackle.

JD: That’s

certainly true. Of course, the

projection system used at Disney made it easy to place the actors and a small

envelope of background into the paintings. (I once had to totally alter the set

an actor was standing on, when the director decided to change the shot design after the live-action was filmed. You can’t do that with a latent-image matte.)

Al didn’t like the rear projection system, and he managed to do shots of type

you’ve described with latent images. But

then he usually had great control of the photography and shot design.

|

| The 'Bank heat pump'... |

Q: Didn’t Albert

even ‘pirate’ some classical gallery

masterpieces in his spare time so that his old pal Alfred Hitchcock could have

duplicate paintings?

JD: Hitchcock maintained two homes, but the

original masterpieces in Hitchcock’s collection could be at only one location

at a time, so ‘Hitch’ asked Al to duplicate the classic paintings.

Q: A

friend of mine in Germany (who’s also a big matte fan) actually owns an original Whitlock gallery

piece, and it’s exquisite Jim. Lucky

guy!

JD: One of my regrets is that I never asked Al if I could acquire

one of his paintings. He had two hanging

in his home that I particularly liked—a view of the ship Cutty Sark under full sail, and a scene of a stately English home

in late afternoon light.

Q: Virtually

nothing has ever been written on Al’s long time cameraman, Ross Hoffman, who

had been with the studio since the early thirties non stop through to

EARTHQUAKE in 1974 – by all accounts, an amazingly versatile and skilled

cinematographer who occasionally got an on screen credit. If you can, please tell us more about Ross?

JD: I don’t know

too much more about Ross, I talked to

him a lot when I was working with Al or visiting him at Universal, but mostly I

asked Ross technical questions, not about his career, per se. Ross showed me the

set-ups used for printing the rotoscoped mattes that were the norm at Universal

for years. The mattes were painted on

cells, using opaque white paint. The

cels were placed on a frame with registration pins that was positioned between

an optical printer and a large studio

lighting unit. With the lighting unit on, the silhouetted cel formed an

aerial-image matte, printing the background scene threaded in the printer but leaving an unexposed area for the element to be added. When

the lighting unit was turned off and the cel was illuminated from the front,

the cell printed the portion of the live-action scene that was being matted

into the duped background.

Q: I just think

back to the huge numbers of mattes and opticals that Ross put together over 40

years and my mind boggles. Aside from

his many ingenious black velvet density matte opticals for all the INVISIBLE

MAN sequels for John Fulton, his truly phenomenal SON OF DRACULA mist morphing transformation

optical effect has to be one of the all time great trick shots.

JD: I’m not a big fan of horror films so I

can’t contribute anything to that topic.

Q: Maybe

so, but Ross was definitely one of

Universal’s unsung heroes who more than earned his keep. Gee Jim, how can you not love TARANTULA or THE

INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN?

JD: like THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN, but I don’t

care much for TARANTULA as a piece of drama, and then some of the mattes are

‘keyed’ incorrectly, with the result that the spider doesn’t always fit behind

the rocks correctly.

|

| A full painting which functioned as the background for a THEY LIVE travelling matte shot (a shot I could never locate in the DVD myself??) |

Q: It’s such a

shame that the authors of the excellent book The Invisible Art – the Legends of Matte Painting didn’t interview

Hoffman who lived on into the mid 90’s.

Can you tell us anything at all about the longtime rotoscope artist,

Millie Winebrenner who was also a

mainstay at Universal for decades from those 50’s sci fi pictures through to

EARTHQUAKE or THE HINDENBURG I think?

JD: I met Millie

but didn’t really know her. I had worked

closely with her former assistant, Nancy van Rensellaer during JACK THE GIANT

KILLER. The hand-drawn mattes at

Universal were created on special drawing tables that had camera/projectors

under them, projecting from the bottom the

image to be traced. This eliminated the

shadows of the artist’s hand that occurs when the scene is projected downward

onto a drawing table from above. At

Universal, when the cells had been painted and were ready to be photographed,

the camera/projector was rotated from below the drawing table to a position

above the table, permitting the artwork to be photographed. Sounds like a major engineering challenge to

me, but it obviously worked.

Q: Al

once wrote for American Cinematographer that Millie used to paint full size

sheets of glass for some roto shots against his paintings, requiring sometimes

70 or so individual full sized matte glasses for a single pass in the days

before cels. That must have been some

major undertaking?

JD: The

use of glass seems odd, since ‘cels’ have been around since before Al Whitlock

started painting mattes. Perhaps it was

due to the heat of the lights. I remember

that when Al first told me he was going to try rotoscoping live action and

matting it in front of his paintings using out-of-focus cels, I was dubious,

because when I had asked Nancy van Rensselaer to make cels for an animated spilt screen during JACK THE GIANT KILLER we

had gotten a very noticeable dark matte line because Nancy didn’t make

complimentary cels with a gap between them as I requested (usually necessary

when doing out-of-focus splits against light backgrounds). I know that, initially Al planned to use only

one set of cels. I don’t know how he

solved the non-linear reproduction of out-of-focus images. One of Al’s tricks was to film the actors in

front of a crudely-painted backing that had colors and tones similar to the

matte painting in the area behind where the matted actors would appear. That way, the slight intentional oversizing

of the out-of-focus matte would not clip into the actors but would blend with

the background. It certainly worked

well.

Q: I found out

recently that both incoming and

outgoing Universal matte painters, Al Whitlock and Russ Lawsen respectively,

painted on the same 1962 feature – TARAS BULBA, which was Lawsen’s only on

screen credit that I’ve ever been able to find.

The photographic effects were split between 3 providers: Universal,

Butler-Glouner and Howard Anderson, so I’m not sure just where Whitlock fitted

into this jigsaw puzzle as he worked for all three. Al painted those chasm shots while Russ

handled the city paintings I’m told by Al’s friend Rolf Giesen.

JD: All I can add

is that I saw one of Russ’s TARAS BULBA city paintings at Universal around

1964. But I

recall that Howard Anderson was involved with some of the chasm scenes, so it’s

possible that Al painted for The Anderson Company on TARAS BULBA.

Q: I’ve

never met nor read accounts from anyone who has actually seen one of Lawsens’ paintings, at least someone who’s still

around. I don’t think even the authors

of that terrific matte painting coffee table book came across any of them. I asked Bill Taylor whether any of Lawsen’s

mattes still existed at Universal and he told me that by the time he had joined

in late 1974 there were no mattes that pre-dated Whitlock’s work. My readers would be most interested in your

memories of Russell’s matte if you can stretch your memory back that far Jim?

JD: Regarding the Russ Lawson painting: It didn’t make much of an impression on

me. I remember it as being smaller than

Al’s paintings. It wasn’t stashed in the

back somewhere. Al just reached down and

lifted it up from somewhere near by. It

seemed to be ‘flat’ in terms of

reflectivity, but that may be a trick of my memory. Al’s paintings always seemed glossy (because

they were). I’m sorry I don’t remember

more, Peter. Like many things I’ve

encountered through the years, if I’d known it was going to be of interest

later, I would have paid more attention.

It was a wide view of a city.

|

| An excellent example of Jim's rear screen process as applied to composite matte photography - with this scene from PLANET OF THE DINOSAURS. |

Q: I remember a

fascinating story you told at the Visual Effects Society a few years ago for

their tribute to Albert about his need to “fix” a certain SHENANDOAH matte painting – even though it was some time

after the film had been released. Would

you like to expand on that Jim?

JD: Apparently there had been something about

that SHENANDOAH shot that Al felt was not right, even though he had approved it

for use in the film. Later he realized

what the problem was and pulled the glass out of the storage rack and quickly

made a correction. As I recall it was a

matter of the brightness of a house in the distance. Al lightened it with a few deft strokes, stood

back, looked at the painting and was satisfied, at last.

Q: Can you

remember the shot? There were around six

mattes in that film – one of the many shows he painted on for director Andrew

V.McLaglen.

JD: It’s the last

one in the film.

Q: Oh yes, I know the shot very well – with the horsemen

crossing the stream to the farmhouse, right? Would you tell us the most valuable lesson(s)

you learned from your time with Albert?

JD: That’s

complicated. I cover that at some length

in my memoir. But in essence Al taught

me to “be fearless and to paint the truth”.

|

| The Effects Associates crew with miniature set for THE STUFF |

Q: Bill Taylor

said that Al always painted very “flat” – avoiding any build up of excess paint

which might cause shadows or pin points of light.

JD: Yes, the glints from the micro bumps in the

paint were sometimes a problem for Al.

One of my first assignments for Al was to scrape down the surface of one

of his paintings, using the flat edge of a razor blade, so Al could repaint

that area. That was fairly daunting, but

it didn’t do as much damage to the painting as I thought it might.

Q: I

shudder at the thought Jim….new ‘green’ matte assistant armed with razor blade

and doing his utmost not to do the unthinkable?? Must have been a palm sweating occasion?

JD: first time I did it I was very worried.

Q: Come

to think of it, I can recall several old time mattes, always colour shows,

where ‘glints’ and ‘pops’ seemed incongruous with the painted part of the scene

– especially in night skies.

JD: Yes,

it’s always difficult to get the lights at an angle where that doesn’t

happen—probably impossible. Of course

polarizing the light helps (as is done in cartoon cel photography) but a lot of

light gets absorbed by the polaroid filters.

During EARTH II at Fox, we oiled Matt Yuricich’s star-field paintings

immediately before photography. This

helped eliminate any specks of dust that would show against the black of outer

space.

Q: To the best

of your knowledge, was the original negative matte process utilized elsewhere at that time or was Al the

only real advocate of the method?

JD: Disney did some

original negative mattes on occasion (as in the shot in which Sean Connery and

Janet Munro run down the hill in DARBY O’ GILL). I had done a 16mm latent matte composite test

earlier, and I started doing it again after working with Al.

Q: Some effects

departments such as MGM were staunch advocates of that complicated duplicating stock process weren’t they –

the method later adopted by Doug Trumbull and co for Matthew Yuricich to use on

all of those projects?

JD: I think you are referring

to color interpositive dupes a.k.a. color intermediate stock dupes.

There may be some confusion here as to the complexity. Running a single interpositive is less

complex than running three black and white separations in three separate

passes—less complicated for the cameraperson.

However, for the artist, color interpositive dupes could be difficult,

because that stock ‘skewed’ the colors and contrast of the painting.

Clarence Slifer at

MGM had an interesting variation on the use of this stock. That variation originated before IP stock existed, when

Slifer used positive Technicolor prints to dupe certain elements during GONE

WITH THE WIND by photographing the aerial image formed by what amounted to a projector

without a lamp house. Later the

interpositive stock yielded a better color reproduction than duplicating a

viewing print. It was also easier to

repeat moves twice instead of four times, as would have been necessary if color

separations had been used. Clarence’s

big ‘gimmick‘ was using the precision lens-move capabilities of an optical

printer without a lamphouse to scan across the film being duplicated, and to

then repeat the same moves with the interpositive and the printer movement

removed from the printer, this time photographing only the painting. The duping and hold-out mattes could be on a

foreground glass (for soft blends) or incorporated into the painting as a clear

area, through which a white duping board was

photographed with the painting in silhouette. Or through which a black

background was visible while the painting was illuminated and being

photographed.

Not many studios used aerial-image dupes (although those

were popular for cartoon work). More

often, inter-positive stock was bi-packed in a

standard matte camera, but moves on paintings could not be made that way.

|

| One of Jim's mattes from the film BUGSY. |

Q: Poor

Matthew had to be!

JD: Yes. He occasionally complained about the fact

that he was obligated to use that system in many of his employment

situations. I remember him saying that,

to get the right shade of green trees he had to paint in “baby-shit brindle brown” tones

Q: Yes,

I’ve heard that delightful turn of phrase from Matthew. I don’t think Windsor & Newton have that particular hue on the market any longer! I sure don’t have any in my box of oil

paints.

|

| Jim's painted prison complex as seen in the excellent under rated Jon Voight film RUNAWAY TRAIN |

Q: Film Effects of Hollywood has been a major

contributor on the LA effects scene for many years and I know you worked there

for a time on IT’S A MAD, MAD, MAD WORLD.

Linwood Dunn had a long history at RKO with Albert Maxwell Simpson – did

you happen to know Simpson by any chance?

I ask because there is so little known about the man and he was one of

the veteran artists who, like Jan Domela who had an epic length matte career

spanning way back to the twenties. I

learned recently that Simpson painted some of the many glasses on KING KONG,

along with Henry Hillinick, who was Matt Yuricich’s mentor.

JD: No, I didn’t know Simpson,

unfortunately.

Q: Bill Taylor

told me of a wonderful Al Simpson oil painting which used to grace the wall of

Linwood Dunn’s office at Film Effects of Hollywood. Do you recall that?

JD: There was a

painting from THE GREAT RACE that Lin said had been painted by Simpson. That was on the stage and showed an Alaskan

dock and trading post. . In the front

hall of Film Effects was a large painting from WEST SIDE STORY. I don’t know who painted it.

By the way, the most impressive painting I ever saw hanging

in a Hollywood office was a western landscape done by

matte artist Jack Shaw (but this was a fine-art painting). It was in the office of Producers Service

Company—suppliers of optical and effects equipment.

Q: Yes,

Jim Aupperle has that GREAT RACE painting now, though the previous owner sawed

off the black matte across the lower area.

A nice painting though. Jim sent me some great close ups of Simpson’s

brush work from that one. That show was

jammed with good matte art. On Jack

Shaw, I wonder if that painting you referred to was one of the ‘War Eagles’

conceptual oil paintings which Harryhausen spoke of as being “still around somewhere”? Apparently Jack painted a couple which

totally impressed Ray and Willis O’Brien!

JD: The painting at Producers Service Company was a view of a

western plain, so don’t think it was for WAR EAGLES. Perhaps it was something done for GWANGI, but

I tend to think it was art for its own sake.

Q: Would I be

correct in suggesting that WHEN DINOSAURS RULED THE EARTH was your first full on visual effects project? Could you tell us, briefly

about the origins of that assignment and how it evolved?

JD: That very complicated story is covered in

detail in my memoir, where it consumes many pages. It started with Lin Dunn recommending me to

Warners

Q: To what

extent did you have control over the design and direction of the sequences

involving stop motion and other types of effects?

JD: The

screenplay had been almost completely written by the time I joined the film, so

my control over basic content was limited.

However, I had a lot to do with the fine tuning of the sequences,

including the shot design. I was the

second unit director. I directed or

co-directed all the scenes that would have stop motion added to them, and I

also directed some scenes that did not involve animation (usually with doubles

for the principle actors).

Q: I’m aware of some misinformation surrounding the matte work on

WDRtE, with even this very blogger getting the story wrong in a recent Hammer

Films matte article. based upon incorrect information published elsewhere.

Could you clarify the situation for us Jim?

|

| One of the many spectacular glass paintings Jim executed for WDRtE. |

JD: I learned of

the misinformation only through your blog on Hammer Films. Prior to that, I hadn’t realized there was

any misinformation. My short answer is

that I did most of the glass paintings used in the film. Les Bowie or his company did the final shot

in the film. No other paintings by Les

appear in the film, unless he helped

Brian Johnson, who did the insert shots of the rising sun and the

forming moon at the Bowie facility. Ray Caple collaborated with me on one glass

painting and did another entirely himself.

I did the composite photography.

The very wide establishing shot of the sand tribe village was done for

me by the Shepperton matte department. I

don’t remember the name of the artist who did the painting. That painting and the composite were very

good.

Q: That other artist was probably Doug Ferris as I think he’s

included it in his filmography. I

was always under the impression that WDRtE was a stressful experience for you –

having to wear so many hats. How much

scheduling pressure was there to pull off so many stop motion, matte and

process shots?

JD: The problem

wasn’t having to wear so many

hats. Not being allowed to wear many

hats is what creates stress. The

problem was not having enough time to plan and budget the production. Six weeks is not enough time to plan a film

with over 125 effects shots—particularly when, at the

time I joined the film, the

script still needed much alteration to make things feasible. There was enormous pressure, due to the

addition of over twenty unplanned glass paintings. The original plan was to have two or three. Then, a high-speed water miniature sequence

that I was told was scheduled to be filmed in a tank at Shepperton ended up

being filmed by me in stop-motion because the cost of the tank lighting crew

proved to be too expensive for the producer’s budget. The delay that followed was not due to the

stop motion but to the numerous

location-scouting trips I was required to go on in an attempt to find a body of

water where we could film in sunlight.

Eventually I refused to keep looking and did the shots with stop motion

and rear projection. And so on, and so

on.

|

| Foreground glass painting and stop motion set up for a scene ultimately deleted. |

Q: Ray Caple is

a bit of an enigma for me. I tried to do

a profile on his career in one of my blogs, though information is hard to come

by. He apparently started as Les Bowie’s

apprentice at age 15 and did much of Bowie’s

painting on the Hammer films, always without credit. Ray was reportedly a very private and

insecure fellow who preferred to do all of his own camerawork and compositing

at his home studio. Can you tell us more

about your interactions with Ray?

JD: Well, I liked Ray a lot. I wish Al Whitlock had recommended him

sooner. I think we would have had fun

working on the film. Ray didn’t seem

insecure to me. However, at the time of

WDRtE, Ray was involved in some serious life problems, and I don’t think he was

able to give his full attention to the work he did for me.

Q: Ray was one

of those all too familiar uncredited matte artists for much of his career, with

I think THE BATTLE OF BRITAIN

being his first on screen credit billing.

Brian Johnson told me that Ray was an amazing painter and someone with a distinctly ‘Welsh’ sense of humour. His ‘Fortress of Solitude’ painting for

SUPERMAN is one of my favourites.

JD: Yes, and

other paintings of Ray’s I saw later were VERY impressive.

Q: The workload

on WDRtE was great and you were forced more or less to seek assistance with

some of the mattes and other effects shots.

Among the people you sought the services of was Peter Melrose who had

learned the artform alongside Al Whitlock and Cliff Culley back at Rank Studios

in the very early fifties. Could you

comment on Peter and his brief tenure on your film?

JD: The short

answer is: Peter was a good artist—very professional. He started a painting for me using the same stage at Bray Studios that I was using. The producer laid him off during the

Christmas holiday to save money—thinking she could rehire him later. Peter was offered NICHOLAS AND

ALEXANDRA. He accepted that assignment

and we lost his services. This started

my ‘never ending’ quest for other matte artists.

Q: Peter was an

occasional matte artist at Shepperton, alongside Gerald Larn and Doug