years ago, the magic of the motion picture matte painter.

Pete’s Editorial:

|

Jim Danforth's glass shot for IT CAME UPON THE MIDNIGHT CLEAR

|

With regard to my last blog article, CATHEDRALS OF MATTE ART, in my haste I neglected to include a couple of additional great mattes by two of the industry’s biggest talents in the matte painting field, Jim Danforth and Ken Marschall.

It’s always a delight to be awakened

to any matte shot that I’ve never before seen, and in many cases as being from a film I’ve never heard of. Effects veteran Jim Danforth’s work has been covered here in great detail - as an animator and overall special effects designer and provider as covered in my retrospective

for his Oscar nominated 1970 picture WHEN DINOSAURS RULED THE EARTH, as well as an extensive career interview covering Jim’s longtime industry experience as a matte artist. We never quite got to cover all of Jim’s matte assignments unfortunately, so I was delighted to receive the following matte of some heavenly Pearly Gates and a technical description from Jim recently. This lovely shot is from a made for television film titled IT CAME UPON THE MIDNIGHT CLEAR (1984) that I’d never heard of until now.

Jim outlined his glass shot as follows: “It's from the Columbia TV movie It Came Upon The Midnight Clear. It's a cathedral of sorts. I comped it via rear projection. It has double-exposed oscillating 'heavenly rays' generated via rotating slit gags. There was also a traveling matte I used to lighten the faces of the actors lined up at the heavenly gates (necessary because the DP ordered the haze blown out of the stage before I arrived on set. Without the haze, the lighting was too contrasty”. It’s a great shot and I appreciate Jim sending me the frame.

----------------------------------------------------

|

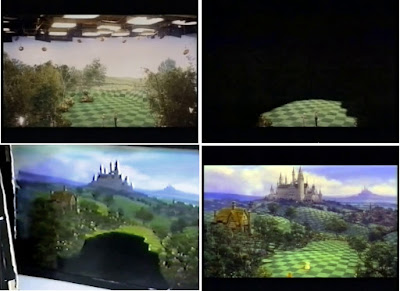

One of Ken Marschall's amazing matte painted shots from MY BOYFRIEND'S BACK (1993).

|

Although I included a few of Ken Marschall’s mattes in the same article I accidentally omitted a couple of superb mattes that Ken did for a film titled MY BOYFRIEND’S BACK (1993) - a film also known in some quarters as JOHNNY ZOMBIE apparently - which depict a heavenly ‘cathedral’ from two vantage points to wonderful effect. Beautifully painted in acrylic atop special high gloss black coated artists card measuring not much more than an A3 sized sheet of paper, as was Ken’s preferred modus operandi, and often painted on Ken's kitchen table at home, which must in itself be unique in the world of matte magic, the original negative composite was shot and put together by Ken’s longtime associate, visual effects cameraman Bruce Block at their small company

Matte Effects, sited ever so discretely in a backroom of Gene Warren jnr's

Fantasy II vfx house.

|

A reverse view of the same heavenly cathedral as painted by Ken Marschall and composited by Bruce Block for MY BOYFRIEND'S BACK (aka JOHNNY ZOMBIE).

|

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A CAREER PORTRAIT OF A MASTER:

THE MATTES AND VISUAL EFFECTS OF ALBERT WHITLOCK - Part One

I love traditional matte art and old school ‘trick photography’. That will surely come as little surprise to my readers. I simply cannot get enough of it, no matter the genre, no matter the vintage, no matter the film, be it a timeless classic or a Poverty Row 'B' movie; no matter the artist or specialist responsible. The matte painter’s artform has no boundaries for me. I admire it for the purity, simplicity and honesty of the ‘trick’ - where the wool can be collectively pulled over our gullible eyes and have us believe that what we are seeing up there on the silver screen is fact, when as was so often the case, so many shots, scenes and set pieces were mere fiction, created by highly skilled artisans just by way of brushes, pigments, a smooth support and a steady camera.

For as long as I can remember, I have admired so many of the individuals responsible for achieving all of these magical shots and memorable moments. The hall of fame of matte shot giants could almost read as: Walter Percy Day, Jack Cosgrove, Norman Dawn, Emil Kosa jr, Chesley Bonestell, Paul Detlefson, Fitch Fulton, Jan Domela, Emilio Ruiz del Rio, Mario Larrinaga, Matthew Yuricich and of course the great Peter Ellenshaw just to name but a few, and these being just some of the ‘names’ that were fortunate enough to get a screen credit in the oddly covert side to the entertainment industry where motion picture ‘trickery’ was kept as far under wraps as an entombed Egyptian Pharaoh and rarely spoken about. Some studios and heads of departments would go to extraordinary lengths in order to keep their special effects secrets buried, with a general understanding that ‘what happens in the matte department, stays in the matte department’.

|

| A most youthful Albert shown here at work, probably at Pinewood 1940's. |

The specialist celebrated in this blog article however, would view things quite differently, and open up those locked doors as we shall discover.

I’ve admired all of the above gentlemen, as well as the countless other, mostly anonymous and long forgotten artists from the matte business for decades, though I must say that there has always been

one name in particular whose work has truly stood out in a class of its own and was largely instrumental for pulling me into this endlessly fascinating aspect of film production, and that name is Albert Whitlock.

Although I have previously covered a great deal of Whitlock’s work in several blogs - an earlier, somewhat lighter career piece as well as a number of ‘stand alone’ examinations on some of his specific films, such as his Hitchcock pictures for example, it is my aim here to present as

full and as comprehensive study of Albert’s matte and effects work as possible.

|

| Three greats of FX, Jim Danforth, Linn Dunn & Albert enjoy their ASC lunch |

I will be documenting not only the familiar shots - though for the most part now in spectacular

high definition for the first time - but also a substantial number of rarely seen, forgotten, lost and completely new matte shots that I have been able to uncover and archive by one means or another. What follows, I hope, will be as complete a retrospective as has been published to date, and as such will occupy at least two blogpost articles

(or maybe three, depending on how it goes, as I don’t ‘prep’ any of this beforehand and just ‘attack’ the blog in one giant almighty swoop and hope for the best). I’m thrilled to be able to present scores of new Whitlock shots, with a great many derived from excellent quality sources that only now revealed the ‘trick’ to me when viewed in a fresh, higher quality format, whereas until now some shots had entirely passed me by undetected, even in shows that I thought I knew quite well! I’ve also acquired excellent quality images of some of Whitlock’s original matte paintings that are still in the care of a few private collectors as well, just to add some icing to the proverbial cake, and they are sensational.

|

| Whitlock surveys a VistaVision matte set up, circa late 1960's. |

In an effort to be as complete as possible, I have also included some examples of likely Whitlock scenic backing art from his early years at Gainsborough Studios in London, as well as a number of ‘educated guess’ matte shots in that I have no real concrete evidence as to their provenance other than various factors - which I will outline in each case - pointing toward a strong possibility of Albert having had involvement such as stylistic attributes and knowledge that the man was in fact employed at certain studio effects departments at particular times or freelancing for specific contractors on a regular basis. As I say, some of those shots are

assumptions on my part, but I believe many of those to quite likely be candidates of Whitlock’s work during that tenure.

|

| Face to face: Two masters of their respective crafts. |

Those familiar with my blogs will know that I, at times, have a tendency to drift off-topic, and this blog post is no exception. Hey, I love movies -

all aspects of movies, so I'll occasionally talk about favourite actors, memorable lines, directors, cameramen, sound effects guys, Oscar injustices, old time movie houses from days gone by and

even trailer voice-over artistes(!) Just humour me guys!

Oh, and, you might wonder at the sheer numbers of frames included in todays blog? Well aside from the fact that Albert did a

lot of matte shots and other work throughout his very long career I've decided that in order to better appreciate certain key VFX shots, especially where animation or special gags of some description have been a vital component, to upload an entire sequence as individual frame grabs which after being clicked on may be toggled through to enjoy the magic in motion, such as moving clouds, animated shadows and complex interactive lighting tricks that enhanced so many of Al's shots. I don't have a clue about making 'gif' files or inserting 'quicktime' clips, so this is as good as it's going to get here folks. But hey, it's straightforward and it achieves what I want it to achieve!

*I’d like to express a special nod of gratitude to several people: Domingo Lizcano, Tom Higginson, Jim Davidson, Pam Carpenter, Chris Shuler, Syd Dutton, Jim Danforth & Thomas Thiemeyer for their various contributions, and in particular, Bill Taylor, who has been incredibly helpful with recollections, clarifications, technical explanations, industry gossip and an amazing memory.

*I’d like to express a special nod of gratitude to several people: Domingo Lizcano, Tom Higginson, Jim Davidson, Pam Carpenter, Chris Shuler, Syd Dutton, Jim Danforth & Thomas Thiemeyer for their various contributions, and in particular, Bill Taylor, who has been incredibly helpful with recollections, clarifications, technical explanations, industry gossip and an amazing memory.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Born in London in 1915, Albert John Whitlock’s early life was very much one of a working class existence within the very strongly defined ‘class system’ that was, and probably still is to a slightly lesser degree, Great Britain. Not uncommon for the time, able bodied young lads often left school after only a few years of basic education in order to help out the family financially. Albert left school at 14 years of age and through a relative was able to gain minimum waged, entry level work in 1929 at London’s Islington film studio as a general ‘dogs-body’ and factotum.

Alberts first foray into the glamour world of movies wasn’t quite so glamourous, was to hand out bags of nails to the carpenters and set builders in the studio. Whitlock eagerly took on the work and did just what he was told as it was the great depression and work was work. From this low level entry into the motion picture business the then 19 year old Cockney would gradually see various avenues open up for him which would definitely broaden young Albert’s horizons without question. If there ever was a case of being in the right place at the right time it was certainly true for him with these formative years at Islington.

|

| The effects stage at Gainsborough, possibly for THE GHOST TRAIN (1941) |

In addition to the mundane day to day storemans chores, Whitlock would find himself drawn into a quite surprising array of other duties. One was to deliver new release prints across London on public transport, which to those of the ‘digital age’ may think unremarkable until you understand that those 35mm reels were nitrate film - with nitrate being an

incredibly combustible film base that was the result of many a projection room inferno and theatre conflagration until the arrival of acetate ‘safety film’ many years later

(the film had a propensity to decompose and become quite unstable when stored in the film vault as I personally witnessed once). Coincidentally, the young Whitlock would later work in a junior behind the scenes capacity on an Alfred Hitchcock picture, SABOTAGE (1936) in which, in one unforgettable sequence, a child carries a similarly disguised package on a London double-decker bus which to our shock and horror is in fact a bomb and blows the bus

and the kid to pieces! They don’t make ‘em like that any more.

During those early days, Albert would also gain experience as a young bit part actor, appearing in numerous British films as page-boys, newspaper boys and other blink and you’d miss it bits. When not acting, the young fellow was enlisted as a helper to on-set electricians, cameramen, scenic painters and just about anybody on the lot with all of this back and forth activity obviously before the industry became so heavily unionised and militant that the mere thought of lending an unauthorised hand to another discipline on the soundstage could result in an instant ‘walk out’ and strike!

The young Whitlock would run into the actors such as Charles Laughton on DOWN RIVER and Conrad Veidt on JEW SUSS as well as Boris Karloff on THE GHOUL, who according to Rolf Giesen, didn’t even give him a tip, unlike the others!

|

| The Schufftan Shot explained, circa 1931. |

Whitlock would also find much to do at Gaumonts Lime Grove Studios in London where to begin with he was the ‘fetch and carry boy’ who was expected to come running whenever somebody yelled out “Boy”. According to historian and close friend Rolf Giesen:

“One single name that Al mentioned repeatedly was that of German born art director Alfred Junge.” By good fortune Albert would go on to be assistant to the same respected art director Alfred Junge as well as working in the miniatures department for the Hitchcock film THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934) in addition to showing some flare for signwriting, which he had learned at night school, that would see him on many a film set painting a wide variety of signage as required. Albert apparently worked with Junge on the 1937 version of KING SOLOMON’S MINES and it’s thought that this film may have been the one which made Albert aware of ‘glass shots’ and their usefulness. Italian born effects expert Fillipo Guidobaldi was in charge of the special effects department and he and Albert’s paths would cross again later on at Pinewood. Whitlock spoke on several occasions of his experiences during that time as he found himself exposed to so many incredibly talented technicians, cameramen, artists and other creative folk who had gotten out of Europe as World War II loomed close on the horizon.

Probably the earliest exposure to ‘trick work’ would have been when Whitlock was asked to assist the set up of the Schufftan Process shot

(**named after its inventor, German cinematographer Eugene Schufftan - sometimes billed as ‘Shuftan’ - the process was a superb, highly effective in camera method of combining multiple elements onto the original negative by clever use of a partially scraped away mirror and deep focus photography, all done right there on the set, the method was frequently applied throughout the 1920’s onward, especially in Europe and the UK, and even made it’s invisible mark in Disney’s wonderful DARBY O’GILL AND THE LITTLE PEOPLE (1959) and was ingeniously applied by Les Bowie to the famous closing shot of Hammer’s 1970 film WHEN DINOSAURS RULED THE EARTH ).

|

| German fx man Willi Horn with a typical Schufftan set up in the 1930's. |

Eugene Schufftan, as a sought after D.O.P would receive an Oscar for his outstanding black & white cinematography on the terrific 1962 Paul Newman picture THE HUSTLER.

Al’s friend Rolf Giesen told me about the Schufftan experience as Al had recounted it:

“Albert watched two experts from Germany handle the Schufftan Process and said ‘One was a Nazi, the other was not. They would make a big fuss and hide behind black velvet’. But Albert found out that the process basically was really quite simple. He remembered the technique and later suggested it to do the effects for Disney’s DARBY O’GILL in a similar way. This however was his only creative input on that picture and he was reduced to help with a few mattes.”

|

| Some Whitlock scenic backings from Gainsborough. Top row: THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934) and WE DIVE AT DAWN (1943). Bottom row: THE 39 STEPS (1935) and CARAVAN (1946). |

|

| Scenic backing artists at work. |

Meanwhile, Albert’s artistic horizons were opening up. He found his calling as a scenic backing artist and mastered the use of the ‘big brush’. If you don’t use a big brush, it’ll never get done.

In later years Whitlock often spoke of his mentor in England, though he never named him directly. It’s most likely that this mentor was fellow scenic painter

Albert Julion who himself would go on to various art director assignments and also have a successful matte painting career with Wally Veevers’ department at Shepperton for a number of years and was highly respected in the craft as Vincent Korda’s favourite matte artist. Many well known English matte artists such as Bob Cuff, Gerald Larn, Peter Melrose and Doug Ferris all spoke highly of Julion who, unfortunately died relatively young in his fifties and left quite a gap in the talent pool of the Shepperton matte department.

Among the films Whitlock worked as a scenic backing painter in England during his early years were several Alfred Hitchcock shows, THE 39 STEPS (1935), SABOTAGE (1936), YOUNG AND INNOCENT (1937), THE LADY VANISHES (1938) and JAMAICA INN (1939) as well as other productions of the period such as CARAVAN (1946) and MADONNA OF THE SEVEN MOONS (1947).

Even once he had graduated into full-on matte work it was not unusual in the British studios at the time for the matte artist to be assigned to scenic backings in addition to glass shots and miscellaneous other special effects jobs. The typical British effects man tended, out of necessity, to be more broad ranging in experience as opposed to their US counterparts who tended to specialise in particular defined fields.

|

Scenic backings that Whitlock would likely have had a hand in. Top row: THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934) and THE LADY VANISHES (1938). Bottom row: CARAVAN (1946) and THE WICKED LADY (1945).

|

|

| Al's first matte assignment came with an actual on-screen credit! |

Whitlock’s career would bounce between scenic backings, signwriting, miniature construction and meticulous lettering on sheets of glass for movie main titles and credits. He even hand painted the famous Gainsborough lady logo that would grace the start of many a British picture through the 1930’s and 40’s. His first venture into matte painting work came about when the original matte painter assigned the task (possibly Albert Julion) left to take up an art director’s post at the studio. Whitlock was a well established scenic artist by that time and so was deemed the obvious choice to take on the mantle of matte painter. The film was the Dennis Price headlined period drama BAD LORD BYRON (1949) where Al was to paint an ornate ballroom and a few ceilings. In these early films, Whitlock himself admitted that his

"style was so tight that he was tied up in knots the whole time when painting matte shots", though his subsequent exposure to the style and technique of fellow Brit Peter Ellenshaw a few years later would prove to be a revelation, and, by Albert’s very own admission, his own matte painting ability would advance in great leaps and bounds as a result of observing Ellenshaws' approach and technique that was nothing like he'd ever seen before in terms of spontenaety, looseness and an incredible speed with the brush.

Some texts have stated that Albert trained under the esteemed British trick shot pioneer Walter Percy ‘Poppa’ Day though this is incorrect. Peter Ellenshaw certainly trained under Day, as did several others such as Les Bowie, Judy Jordan and Joseph Natanson to name but a few. What I can confirm is that Whitlock and Day

did in fact meet though not in any special effects capacity. Albert’s friend Rolf Giesen wrote me many stories about Whitlock and mentioned:

“I can tell you for sure that he met Day although he may not have actually worked for him. They both worked on MINE OWN EXECUTIONER (1947), though in different capacities. Perhaps Albert was sent by the art department to visit Day’s studio, but I saw no photographic record of him working in Day’s department, only from his days at Rank. By the way, he called Les Bowie his boss [at Pinewood] and not his mentor. The matte artists Albert mentioned most often were Norman Dawn, Conrad Tritschler, Peter Ellenshaw and Russ Lawson.” In one published interview, Albert described Pop Day as

“a better painter than any of us, though he tended to make his paintings too detailed, which would draw too much attention to them.”

|

| One of Percy Day's matte shots from MINE OWN EXECUTIONER (1947) |

I’ve discussed the work and importance of Dawn, Ellenshaw and even Lawson to a somewhat lesser degree here in previous blogs, some quite extensively, though little mention was made of Conrad Tritschler, whom Whitlock was apparently so fond of. Tritschler was a well known British scenic artist in the London theatre world of the 1920’s and then progressed into motion picture work as a scenic artist, glass shot exponent and miniature effects man for such directors as Cecil B. DeMille, Ed Carewe, Frank Lloyd and Douglas Fairbanks. He painted mattes for WHITE ZOMBIE (1932) and quite possibly for the 1930 Bela Lugosi DRACULA classic among other titles.

|

| A wonderful 'family' portrait of the Pinewood Special Effects Department taken during the making of the Peter Ustinov film HOTEL SAHARA (1952). Not all identified but some are as follows: Back row standing at left is matte painter Cliff Culley. Back row far right wearing hat is electrician Ronnie Wells and standing next to him is physical effects man Frank George. Front row far right is head of department Bill Warrington. Next to Bill smoking a pipe is VFX cameraman Bert Marshall. Albert Whitlock is standing in the middle next to Bert, and lastly, at far left wearing glasses is long time mechanical effects man Jimmy Ackland-Snow. Also present may possibly be fx man Bert Luxford. *Many thanks to Jimmy Snow's grand daughter Brigette for sharing this and other great photos with me.... very much appreciated. |

|

| Miniatures maestro Fillipo Guidobaldi on CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS |

It was around 1946 that Albert began work at J. Arthur Rank’s Pinewood Studios where he continued painting both scenic backings as well as glass shots. The special effects department at the time was under the control of Bill Warrington. Joan Suttie I believe was head of matte painting for some time until former scenic backing painter, Canadian born Les Bowie came along and eventually became chief matte artist for the studio. Albert worked under Les along with other scenic artists turned matte painters Peter Melrose and Cliff Culley. Albert must have been quite high in seniority as he alone among the artists actually received screen credit on a number of productions - usually with department head Warrington or Italian born miniatures expert Fillipo Guidobaldi with whom Whitlock had previously worked at Gaumont several years earlier.

|

| Matte painter and all round effects expert Les Bowie. |

Peter Melrose would go on to a long career in both scenic and matte art

(and he’s still with us) spoke about the Pinewood era where he and Albert would work together on glass shots and often devised multi-plane glass shots with numerous details painted as separate layers to allow depth to a trick shot, sometimes combining these with miniatures.

Among the films Albert worked on at Pinewood were the Technicolor adventure CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS (1949), SO LONG AT THE FAIR (1949), ROMEO AND JULIET (1953) as well as the three critically acclaimed Somerset Maugham pictures QUARTET, TRIO and ENCORE from the late 40's and early 50's.

|

| A typically large scenic backing being painted at Pinewood Studios by Al's former colleague, Cliff Culley. |

|

| Peter Ellenshaw on SWORD AND THE ROSE. Note Al's title glasses ready |

From the early 1950’s Walt Disney had begun to experiment with full live action features in addition to the well loved cartoon shorts and full length animated classics. Several of these, such as the highly successful ROBIN HOOD AND HIS MERRIE MEN (1952) would be based, filmed and completed entirely in England. The highly talented matte artist Peter Ellenshaw had already had his work cut out for him with Disney’s previous, and in fact the first live action adventure, TREASURE ISLAND (1949) and had scores more mattes to paint for the succeeding films that would number near 100 shots all told for the four feature films in total.

It was on two of these pictures that Albert Whitlock joined Ellenshaw's department as an assistant. THE SWORD AND THE ROSE (1953) and ROB ROY THE HIGHLAND ROGUE (1954) were Albert’s first introductions to the Disney empire. I know that Al designed and hand lettered the main title 'cast and credits' glasses for both and may have participated in helping Peter with some of the mattes too, though I have no firm evidence.

In an interview in 1979, Peter remarked that he very well remembered meeting Albert for the first time as he had just finished a glass painting for SWORD when the two men were introduced, though what made it unforgettable was that right at that moment a large painted glass matte snapped as Peter was moving it and a shard of glass hit him just below the eye. An inch higher and Peter may well have lost an eye! I believe that another of Albert’s Pinewood colleagues, Cliff Culley, also contributed to THE SWORD AND THE ROSE, though in what capacity I do not know. Later on Cliff was one of the uncredited matte painters under Ellenshaw on one of Disney’s most impressive special effects extravaganzas, IN SEARCH OF THE CASTAWAYS (1962) alongside another important name in the field, Alan Maley, in what was a massive matte shot show if ever there was one.

|

| Walt with Albert in the late fifties. |

In later interviews with historian and co-author of the utterly indispensible

The Invisible Art-The Legends of Movie Matte Painting, Craig Barron, Whitlock admitted that he learned so much just by observing Peter and watching over his shoulder. Albert remarked:

“Peter didn’t teach me, he just let me observe him.” Albert would often refer to Peter's influence and just how it shaped his own abilities. Disney reverted to stateside in-house production for most of its subsequent films, with a few exceptions such as the remake of THE PRINCE AND THE PAUPER and the aforementioned IN SEARCH OF THE CASTAWAYS both made in 1962. Walt apparently liked Albert and struck up quite a friendship, the result of which saw Whitlock invited in 1954 to make the journey across the Atlantic with his wife June and sons John and Mark to the Disney Studios in Burbank, California for work, which sounded great in theory but hadn’t been properly thought through. There was no specific ‘work’ for Whitlock! Realising the dilemma, Walt saw to it that Albert had something to do in the meantime, with one of these jobs being to paint - as in house painting - the actual Main Street Theatre in the then new Disneyland theme park. Apparently Albert was also involved in some of the basic concepts for the park as well, though as to what extent I do not know.

|

| One of Alberts hand lettered title glasses for a Disney classic. |

Walt had long planned a big, epic scaled adventure picture - in CinemaScope and Technicolor - that he gambled would be a hit, and it was. The Jules Verne saga 20’000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA (1954) was that epic. Peter Ellenshaw was aware of Albert’s talent for hand lettered main titles and movie credits which lead to Whitlock being responsible for designing and painting the title glasses for the film. The film incidentally won the Academy Award for special effects, with Peter Ellenshaw, Ralph Hammeras, Joshua Meador and Robert Mattey cited, though none of these gentlemen actually received a statuette, as a solitary winning statuette went to The Walt Disney Studio and remained in Walt’s office, though I digress.

|

| Al poses with his Lady Liberty matte for the film MAME. |

Following the well deserved success of 20’000 LEAGUES, Disney went all out producing dozens of live action pictures, with nearly all of these requiring visuals and matte effects of some degree. Ellenshaw's tiny matte department, which was initially sited in a corridor in the animation building, expanded and moved into a fully fledged workshop complete with cameramen and additional artists. Albert was the first to join Peter in this newly formed department, followed closely by former 20th Century Fox artist Jim Fetherolf. Together the three skilled painters shared matte duties on a number of films, always under Peter’s supervision and watchful eye, with the Disney leadership being extremely ‘gung-ho’ on mattes, process shots and all manner of trick work often used extensively.

|

| Al's matte from Disney's DANIEL BOONE,WARRIORS PATH |

Some of the films that Albert painted mattes for included JOHNNY TREMAIN (1957), THIRD MAN ON THE MOUNTAIN (1959), WESTWARD HO THE WAGONS (1956), THE GREAT LOCOMOTIVE CHASE (1956), KIDNAPPED (1960), ZORRO (1960), POLLYANNA (1960), DARBY O’GILL AND THE LITTLE PEOPLE (1959) and Whitlock’s own personal favourite from his time at Disney, GREYFRIARS BOBBY (1961) which was one of the few films in which he was able to receive a screen credit for while at that studio.

Albert would tell interviewer Tom Greene in 1974 that Disney was where he learned a great deal.

"The studio housed tremendous talent and I have to give Peter Ellenshaw credit for being the one who convinced Walt Disney that the artist should be the one looking through the camera and blocking out certain areas, and was the obvious person to do the job."

|

| Detail from an unidentified Whitlock matte painting. |

Albert spent just over five years at Disney and eventually left, rather suddenly, at the invitation of Production Manager George Golitzen, who had worked with Al on Disney's THE PARENT TRAP, and was the brother of Universals art department head, Alexander Golitzen, to join Universal Studios. During this initial period, Al engaged in freelance matte painting requests as well, providing a number of mattes to independent effects houses such as Howard A. Anderson, Butler-Glouner, Film Effects of Hollywood and perhaps some others. Albert accepted the job as head of the matte department at Universal Studios, replacing the then retiring Russ Lawson who had been with the studio since the 1930's and had painted a huge number of mattes for hundreds of Universal films under the visual effects direction of the great John P. Fulton as well as later heads David Stanley Horsley and Clifford Stine. According to Whitlock, Russ who had just inherited a fortune, shook Albert's hand and remarked

"You can have it all!" (meaning the department I presume, and

not the 'fortune').

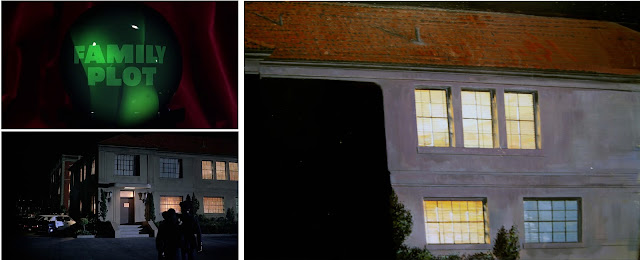

Albert was highly productive at Universal and it wasn't long before the front office knew they were onto a good thing. It is estimated that he worked on around 150 films and television shows, with a great many not being screen credited. Al had already painted on several movies at the studio before any sort of credit, and the first actual credit was an odd one as

'Pictorial Designs by Albert Whitlock' for Alfred Hitchcock's THE BIRDS (1963) for which he painted some 13 mattes. THE BIRDS sealed Al's creative cache with Hitchcock, who would use Albert's services on all of his subsequent pictures. The pair hit it off without question, both being Londoners and of a similar background, not to mention a very junior Whitlock having worked on 3 or 4 of Hitch's very early British films.

|

| Syd observes while Al explains to doco maker Walter Dornish. |

Whitlock's department at Universal consisted of a pretty small group; Matte Cinematographer Roswell Hoffman - who like Lawson had been in the department forever, going back to the James Whale horror pictures of the thirties with the legendary John P. Fulton. Ross, as he was known, was an extremely talented visual effects cameraman and optical man who worked right up to the Academy Award winning EARTHQUAKE (1974). Other staff in the department included Assistant Cameraman Mike Moramarco, who would work alongside Albert for many years to come. Millie Winebrenner and Nancy van Rensellaer were Rotoscope Artists - again long serving effects staffers whose careers went way back. Millie worked through to THE HINDENBURG (1975). Larry Shuler was Albert's Key Grip and would be responsible for building platforms and special rigs for the camera and was among other things a studio fireman and a fine practical joker. Larry passed away just a few months ago and his daughter was kind enough to send me some photos of some of the matte paintings he had up on his living room wall, with these marvellous images featuring at various points in this blog.

Some time ago Larry dropped NZPete a line:

"It was a pleasure to go back in the history of the matte shots. I worked with all of these folks starting in the sixties. Albert was an incredible person to work for . Thanks for the great site. Best regards, Larry Shuler: Key Grip." Following Larry's passing, I had the pleasure of communicating with his daughter Pam, who recalled a great deal: "He was working at Universal before Whitlock arrived. When Al starting setting up an effects department, my dad, Larry Shuler, was transferred to that department at Al's request after working there a few days, this was when Ross Hoffman was there long before Bill Taylor. Ross had been in the Special Photographic Effects Dept for many years since the 30's doing a lot of the westerns and horror pictures, working with Cliff Stein and Russ Harland [Lawson?]. Ross retired at age 75. That's when Bill arrived. Bill actually set up the the effects for the dogs in HOUNDS OF THE BASKERVILLE (1971), from his prior work with Ray Mercer doing a shampoo ad."

|

| Bill Taylor shoots and original negative matte plate. |

Following Ross Hoffman's retirement in 1974 a new specialist entered the department, Bill Taylor. Bill had been working in the field of optical cinematography for many years at fx houses Ray Mercer and Film Effects of Hollywood with Linwood Dunn and had known Albert as a friend for many years after being invited to visit Al at his Universal workshop. Bill recently discussed his initial visit to Albert's studio and subsequent employment with author Tom Higginson:

"His paintings were a revelation to me. Al understood what the camera sees, and he developed all sorts of tricks to animate the paintings". It would be several years later that Bill would actually join Whitlock's department, just as they were getting ready for THE HINDENBURG in 1975.

"Al hired me as cameraman. In those days we had to do lots of shots in a hurry and they had to be very high quality, so we relied heavily on the original negative process. We put up a matte in front of the camera (see example at left) when the live action was photographed. Then we took the undeveloped negative, or the 'held take' and refrigerated it along with a back-up take until the painting was finished. Tests were made on clips that were shot on other rolls. In the final stage, after the last test had been seen and approved, the 'held take' was defrosted and the painting was exposed onto the original negative. So, the result was just absolutely pristine quality".

When compared with

dupe matte shots, that were the most commonly utilised method for many years at all of the other major studios, the fidelity of the Whitlock latent image composite just stood out in a class of its own.

|

| Al's son Mark, himself a matte painter, on location. |

It would be some years later that the O/Neg technique would find a resurgence among a mainly 'new breed' of younger matte exponents such as Rocco Gioffre, Mark Sullivan, Ken Marschall, Robert Stromberg and of course, Al's former apprentice, Syd Dutton. Even powerhouse effects suppliers like Industrial Light & Magic were tentative about embarking on such a seemingly 'risky' approach, and it was only around 1982 that ILM even experimented with Whitlock's

modus-operandi on one shot for the film ET, and they were nervous about that simple moonlit sky split screen. ILM's masters of the artform, Michael Pangrazio and Christopher Evans quickly adapted to the Whitlock approach and would emulate not only the pristine latent image technique but also the effects gags such as rolling clouds.

|

| Al with documentarian Mark Horowitz, 1982 *photo by Walter Dornish |

Whitlock's department stood by quality, and no lesser substitute would ever do. No shot ever passed out of the department without Al's okay. Whitlock was always happy to share his methodology with anyone who asked, and often gave seminars for budding film studies students and visual effects practitioners. Veteran stop motion animator and vfx cameraman Jim Aupperle told me about one of these lectures:

"I'd have to agree that Albert was the master of the art of matte painting. I was lucky enough to see several demo's over the years that Al gave on his work in various films, and I was consistently amazed. He'd always show the shot first as it appeared in the finished film, and I'd look at it and think to myself, 'Okay...I can figure this out'. Then, he'd show the shot broken down into various elements, and how they all combined. My jaw hit the floor every single time."

|

| Albert as photographed by friend Bill Taylor. |

Fellow matte painter Ken Marschall also told me similar stories of when he first went to such a series of lectures in 1976 where notable giants such as Peter and Harrison Ellenshaw, Matthew Yuricich, L.B Abbott and Al were all giving lectures and all of whom showed amazing demo reels that left Ken stunned. Seeing Whitlock's before and after reels was a revelation for Marschall who decided then and there that he just

had to get into visual effects:

"Albert was always my favourite. His work was always so real. I got to meet and talk with Al and Bill there. The whole experience was unforgettable."

Al's

department was constantly busy through the sixties and on into the eighties with not only the myriad of Universal productions on the go, but many outside matte and effects jobs for other studios too, with some being quite unusual. The acclaimed director Robert Altman even used Al to supply a lot of falling snow for his revisionist wintery western McCABE AND MRS MILLER (1971), made by Warner Bros, and even mentioned the fact on the DVD commentary track. Mike Nichols hired Al for a matte and a unique one-of-a-kind visual effect gag on his classic CATCH 22 (1970) which was a Paramount picture. One of the moguls at another Hollywood studio even referred to Al as

"Universal's secret weapon", as he had the ability to bring gravitas to a scene or film, and all on an affordable budget. The workload was considerable, no two ways about it. When, upon the master's retirement in 1985, the studio decided it was high time to cut costs and close down the matte department, and others as well.

One of the last films that Al worked on as a Universal employee was GREYSTOKE. Bill and Syd would wrangle a deal with the studio to maintain the facility and it's equipment which they would pay a rental on under the banner of

Illusion Arts - a company name already trademarked by Bill as part of his side interest in stage magic

(more than just an interest... a true passion, according to Syd, along with watches and old clocks), This arrangement only lasted about a year with the decision to find some real estate to call their own, Illusion Arts moved to a new suburban home, near to John Dykstra's effects house Apogee, and another specialty house Grant McCune Miniatures. Universal did a sweetheart deal on all of the old Whitlock equipment, cameras, optical printers and so forth whereby Dutton and Taylor got what they wanted at a bargain price.

|

| Bill Taylor & Syd Dutton; Al at home; lecture on VFX; Mike Moramarco |

Illusion Arts, as a stand alone matte shot and general visual effects company, proved extremely successful and highly respected effects house and lasted well over two decades. Al would frequently come by and put his head in the door and

"see what the boys were up to". Bill remarked:

"After Al's official retirement he would come in and offer over-the-shoulder advice and some unofficial painting here and there - he couldn't help himself - but didn't take on shots per-se, with very few exceptions like FUNNY FARM." A variety of projects, both large and small, were handed to Illusion Arts, with some quite substantial matte shot shows such as NEVER ENDING STORY 2 (1990) that would see Albert credited as Matte Painting Supervisor, though I don't think he actually painted any of the shots himself, with Syd painting most of them, plus one or two recycled from the first film and a few others done by another British artist temporarily based in Germany.

Albert would continue to paint, purely for his own pleasure at home, though by his own account

"had nothing to say" as far as his private painting went, and would see it pretty much as an enjoyable past time. Sometime in the 1990's Al developed the serious and incurable ailment that affects the neurological system, Parkinson's Disease, which would soon bring to an end the joy he experienced in applying brush and pigments to canvas. That insidious, creeping disease would ultimately lead to Al's death in 1999 at the age of 84. In a very long and diverse career that spanned more than fifty years, hundreds of films and television shows, a pair of Oscars, an Emmy Award and various other nominations and accolades, Albert Whitlock was one of the most respected specialists in the motion picture industry, who not only had achieved a cast iron reputation among producers, directors and studio heads for consistently high quality, yet pragmatic solutions to even the most seemingly insurmountable visual effect problems, he would influence an entire new generation of photographic effects and matte shot practitioners whose subsequent success and mastery of their craft owed so much to Whitlock's guidence, advice and his time tested no-nonsense methodology.

I love traditional matte art and old school ‘trick photography’. That will surely come as little surprise to my readers. I simply cannot get enough of it, no matter the genre, no matter the vintage, no matter the film, be it a timeless classic or a Poverty Row 'B' movie; no matter the artist or specialist responsible. The matte painter’s artform has no boundaries for me. I admire it for the purity, simplicity and honesty of the ‘trick’ - where the wool can be collectively pulled over our gullible eyes and have us believe that what we are seeing up there on the silver screen is fact, when as was so often the case, so many shots, scenes and set pieces were mere fiction, created by highly skilled artisans just by way of brushes, pigments, a smooth support and a steady camera.

I love traditional matte art and old school ‘trick photography’. That will surely come as little surprise to my readers. I simply cannot get enough of it, no matter the genre, no matter the vintage, no matter the film, be it a timeless classic or a Poverty Row 'B' movie; no matter the artist or specialist responsible. The matte painter’s artform has no boundaries for me. I admire it for the purity, simplicity and honesty of the ‘trick’ - where the wool can be collectively pulled over our gullible eyes and have us believe that what we are seeing up there on the silver screen is fact, when as was so often the case, so many shots, scenes and set pieces were mere fiction, created by highly skilled artisans just by way of brushes, pigments, a smooth support and a steady camera. For as long as I can remember, I have admired so many of the individuals responsible for achieving all of these magical shots and memorable moments. The hall of fame of matte shot giants could almost read as: Walter Percy Day, Jack Cosgrove, Norman Dawn, Emil Kosa jr, Chesley Bonestell, Paul Detlefson, Fitch Fulton, Jan Domela, Emilio Ruiz del Rio, Mario Larrinaga, Matthew Yuricich and of course the great Peter Ellenshaw just to name but a few, and these being just some of the ‘names’ that were fortunate enough to get a screen credit in the oddly covert side to the entertainment industry where motion picture ‘trickery’ was kept as far under wraps as an entombed Egyptian Pharaoh and rarely spoken about. Some studios and heads of departments would go to extraordinary lengths in order to keep their special effects secrets buried, with a general understanding that ‘what happens in the matte department, stays in the matte department’.

For as long as I can remember, I have admired so many of the individuals responsible for achieving all of these magical shots and memorable moments. The hall of fame of matte shot giants could almost read as: Walter Percy Day, Jack Cosgrove, Norman Dawn, Emil Kosa jr, Chesley Bonestell, Paul Detlefson, Fitch Fulton, Jan Domela, Emilio Ruiz del Rio, Mario Larrinaga, Matthew Yuricich and of course the great Peter Ellenshaw just to name but a few, and these being just some of the ‘names’ that were fortunate enough to get a screen credit in the oddly covert side to the entertainment industry where motion picture ‘trickery’ was kept as far under wraps as an entombed Egyptian Pharaoh and rarely spoken about. Some studios and heads of departments would go to extraordinary lengths in order to keep their special effects secrets buried, with a general understanding that ‘what happens in the matte department, stays in the matte department’. *I’d like to express a special nod of gratitude to several people: Domingo Lizcano, Tom Higginson, Jim Davidson, Pam Carpenter, Chris Shuler, Syd Dutton, Jim Danforth & Thomas Thiemeyer for their various contributions, and in particular, Bill Taylor, who has been incredibly helpful with recollections, clarifications, technical explanations, industry gossip and an amazing memory.

*I’d like to express a special nod of gratitude to several people: Domingo Lizcano, Tom Higginson, Jim Davidson, Pam Carpenter, Chris Shuler, Syd Dutton, Jim Danforth & Thomas Thiemeyer for their various contributions, and in particular, Bill Taylor, who has been incredibly helpful with recollections, clarifications, technical explanations, industry gossip and an amazing memory. Born in London in 1915, Albert John Whitlock’s early life was very much one of a working class existence within the very strongly defined ‘class system’ that was, and probably still is to a slightly lesser degree, Great Britain. Not uncommon for the time, able bodied young lads often left school after only a few years of basic education in order to help out the family financially. Albert left school at 14 years of age and through a relative was able to gain minimum waged, entry level work in 1929 at London’s Islington film studio as a general ‘dogs-body’ and factotum.

Born in London in 1915, Albert John Whitlock’s early life was very much one of a working class existence within the very strongly defined ‘class system’ that was, and probably still is to a slightly lesser degree, Great Britain. Not uncommon for the time, able bodied young lads often left school after only a few years of basic education in order to help out the family financially. Albert left school at 14 years of age and through a relative was able to gain minimum waged, entry level work in 1929 at London’s Islington film studio as a general ‘dogs-body’ and factotum.

In an interview in 1979, Peter remarked that he very well remembered meeting Albert for the first time as he had just finished a glass painting for SWORD when the two men were introduced, though what made it unforgettable was that right at that moment a large painted glass matte snapped as Peter was moving it and a shard of glass hit him just below the eye. An inch higher and Peter may well have lost an eye! I believe that another of Albert’s Pinewood colleagues, Cliff Culley, also contributed to THE SWORD AND THE ROSE, though in what capacity I do not know. Later on Cliff was one of the uncredited matte painters under Ellenshaw on one of Disney’s most impressive special effects extravaganzas, IN SEARCH OF THE CASTAWAYS (1962) alongside another important name in the field, Alan Maley, in what was a massive matte shot show if ever there was one.

In an interview in 1979, Peter remarked that he very well remembered meeting Albert for the first time as he had just finished a glass painting for SWORD when the two men were introduced, though what made it unforgettable was that right at that moment a large painted glass matte snapped as Peter was moving it and a shard of glass hit him just below the eye. An inch higher and Peter may well have lost an eye! I believe that another of Albert’s Pinewood colleagues, Cliff Culley, also contributed to THE SWORD AND THE ROSE, though in what capacity I do not know. Later on Cliff was one of the uncredited matte painters under Ellenshaw on one of Disney’s most impressive special effects extravaganzas, IN SEARCH OF THE CASTAWAYS (1962) alongside another important name in the field, Alan Maley, in what was a massive matte shot show if ever there was one. Albert was highly productive at Universal and it wasn't long before the front office knew they were onto a good thing. It is estimated that he worked on around 150 films and television shows, with a great many not being screen credited. Al had already painted on several movies at the studio before any sort of credit, and the first actual credit was an odd one as 'Pictorial Designs by Albert Whitlock' for Alfred Hitchcock's THE BIRDS (1963) for which he painted some 13 mattes. THE BIRDS sealed Al's creative cache with Hitchcock, who would use Albert's services on all of his subsequent pictures. The pair hit it off without question, both being Londoners and of a similar background, not to mention a very junior Whitlock having worked on 3 or 4 of Hitch's very early British films.

Albert was highly productive at Universal and it wasn't long before the front office knew they were onto a good thing. It is estimated that he worked on around 150 films and television shows, with a great many not being screen credited. Al had already painted on several movies at the studio before any sort of credit, and the first actual credit was an odd one as 'Pictorial Designs by Albert Whitlock' for Alfred Hitchcock's THE BIRDS (1963) for which he painted some 13 mattes. THE BIRDS sealed Al's creative cache with Hitchcock, who would use Albert's services on all of his subsequent pictures. The pair hit it off without question, both being Londoners and of a similar background, not to mention a very junior Whitlock having worked on 3 or 4 of Hitch's very early British films. When compared with dupe matte shots, that were the most commonly utilised method for many years at all of the other major studios, the fidelity of the Whitlock latent image composite just stood out in a class of its own.

When compared with dupe matte shots, that were the most commonly utilised method for many years at all of the other major studios, the fidelity of the Whitlock latent image composite just stood out in a class of its own. One of the last films that Al worked on as a Universal employee was GREYSTOKE. Bill and Syd would wrangle a deal with the studio to maintain the facility and it's equipment which they would pay a rental on under the banner of Illusion Arts - a company name already trademarked by Bill as part of his side interest in stage magic (more than just an interest... a true passion, according to Syd, along with watches and old clocks), This arrangement only lasted about a year with the decision to find some real estate to call their own, Illusion Arts moved to a new suburban home, near to John Dykstra's effects house Apogee, and another specialty house Grant McCune Miniatures. Universal did a sweetheart deal on all of the old Whitlock equipment, cameras, optical printers and so forth whereby Dutton and Taylor got what they wanted at a bargain price.

One of the last films that Al worked on as a Universal employee was GREYSTOKE. Bill and Syd would wrangle a deal with the studio to maintain the facility and it's equipment which they would pay a rental on under the banner of Illusion Arts - a company name already trademarked by Bill as part of his side interest in stage magic (more than just an interest... a true passion, according to Syd, along with watches and old clocks), This arrangement only lasted about a year with the decision to find some real estate to call their own, Illusion Arts moved to a new suburban home, near to John Dykstra's effects house Apogee, and another specialty house Grant McCune Miniatures. Universal did a sweetheart deal on all of the old Whitlock equipment, cameras, optical printers and so forth whereby Dutton and Taylor got what they wanted at a bargain price.

I love traditional matte art and old school ‘trick photography’. That will surely come as little surprise to my readers. I simply cannot get enough of it, no matter the genre, no matter the vintage, no matter the film, be it a timeless classic or a Poverty Row 'B' movie; no matter the artist or specialist responsible. The matte painter’s artform has no boundaries for me. I admire it for the purity, simplicity and honesty of the ‘trick’ - where the wool can be collectively pulled over our gullible eyes and have us believe that what we are seeing up there on the silver screen is fact, when as was so often the case, so many shots, scenes and set pieces were mere fiction, created by highly skilled artisans just by way of brushes, pigments, a smooth support and a steady camera.

I love traditional matte art and old school ‘trick photography’. That will surely come as little surprise to my readers. I simply cannot get enough of it, no matter the genre, no matter the vintage, no matter the film, be it a timeless classic or a Poverty Row 'B' movie; no matter the artist or specialist responsible. The matte painter’s artform has no boundaries for me. I admire it for the purity, simplicity and honesty of the ‘trick’ - where the wool can be collectively pulled over our gullible eyes and have us believe that what we are seeing up there on the silver screen is fact, when as was so often the case, so many shots, scenes and set pieces were mere fiction, created by highly skilled artisans just by way of brushes, pigments, a smooth support and a steady camera. For as long as I can remember, I have admired so many of the individuals responsible for achieving all of these magical shots and memorable moments. The hall of fame of matte shot giants could almost read as: Walter Percy Day, Jack Cosgrove, Norman Dawn, Emil Kosa jr, Chesley Bonestell, Paul Detlefson, Fitch Fulton, Jan Domela, Emilio Ruiz del Rio, Mario Larrinaga, Matthew Yuricich and of course the great Peter Ellenshaw just to name but a few, and these being just some of the ‘names’ that were fortunate enough to get a screen credit in the oddly covert side to the entertainment industry where motion picture ‘trickery’ was kept as far under wraps as an entombed Egyptian Pharaoh and rarely spoken about. Some studios and heads of departments would go to extraordinary lengths in order to keep their special effects secrets buried, with a general understanding that ‘what happens in the matte department, stays in the matte department’.

For as long as I can remember, I have admired so many of the individuals responsible for achieving all of these magical shots and memorable moments. The hall of fame of matte shot giants could almost read as: Walter Percy Day, Jack Cosgrove, Norman Dawn, Emil Kosa jr, Chesley Bonestell, Paul Detlefson, Fitch Fulton, Jan Domela, Emilio Ruiz del Rio, Mario Larrinaga, Matthew Yuricich and of course the great Peter Ellenshaw just to name but a few, and these being just some of the ‘names’ that were fortunate enough to get a screen credit in the oddly covert side to the entertainment industry where motion picture ‘trickery’ was kept as far under wraps as an entombed Egyptian Pharaoh and rarely spoken about. Some studios and heads of departments would go to extraordinary lengths in order to keep their special effects secrets buried, with a general understanding that ‘what happens in the matte department, stays in the matte department’.

*I’d like to express a special nod of gratitude to several people: Domingo Lizcano, Tom Higginson, Jim Davidson, Pam Carpenter, Chris Shuler, Syd Dutton, Jim Danforth & Thomas Thiemeyer for their various contributions, and in particular, Bill Taylor, who has been incredibly helpful with recollections, clarifications, technical explanations, industry gossip and an amazing memory.

*I’d like to express a special nod of gratitude to several people: Domingo Lizcano, Tom Higginson, Jim Davidson, Pam Carpenter, Chris Shuler, Syd Dutton, Jim Danforth & Thomas Thiemeyer for their various contributions, and in particular, Bill Taylor, who has been incredibly helpful with recollections, clarifications, technical explanations, industry gossip and an amazing memory. Born in London in 1915, Albert John Whitlock’s early life was very much one of a working class existence within the very strongly defined ‘class system’ that was, and probably still is to a slightly lesser degree, Great Britain. Not uncommon for the time, able bodied young lads often left school after only a few years of basic education in order to help out the family financially. Albert left school at 14 years of age and through a relative was able to gain minimum waged, entry level work in 1929 at London’s Islington film studio as a general ‘dogs-body’ and factotum.

Born in London in 1915, Albert John Whitlock’s early life was very much one of a working class existence within the very strongly defined ‘class system’ that was, and probably still is to a slightly lesser degree, Great Britain. Not uncommon for the time, able bodied young lads often left school after only a few years of basic education in order to help out the family financially. Albert left school at 14 years of age and through a relative was able to gain minimum waged, entry level work in 1929 at London’s Islington film studio as a general ‘dogs-body’ and factotum.

In an interview in 1979, Peter remarked that he very well remembered meeting Albert for the first time as he had just finished a glass painting for SWORD when the two men were introduced, though what made it unforgettable was that right at that moment a large painted glass matte snapped as Peter was moving it and a shard of glass hit him just below the eye. An inch higher and Peter may well have lost an eye! I believe that another of Albert’s Pinewood colleagues, Cliff Culley, also contributed to THE SWORD AND THE ROSE, though in what capacity I do not know. Later on Cliff was one of the uncredited matte painters under Ellenshaw on one of Disney’s most impressive special effects extravaganzas, IN SEARCH OF THE CASTAWAYS (1962) alongside another important name in the field, Alan Maley, in what was a massive matte shot show if ever there was one.

In an interview in 1979, Peter remarked that he very well remembered meeting Albert for the first time as he had just finished a glass painting for SWORD when the two men were introduced, though what made it unforgettable was that right at that moment a large painted glass matte snapped as Peter was moving it and a shard of glass hit him just below the eye. An inch higher and Peter may well have lost an eye! I believe that another of Albert’s Pinewood colleagues, Cliff Culley, also contributed to THE SWORD AND THE ROSE, though in what capacity I do not know. Later on Cliff was one of the uncredited matte painters under Ellenshaw on one of Disney’s most impressive special effects extravaganzas, IN SEARCH OF THE CASTAWAYS (1962) alongside another important name in the field, Alan Maley, in what was a massive matte shot show if ever there was one.

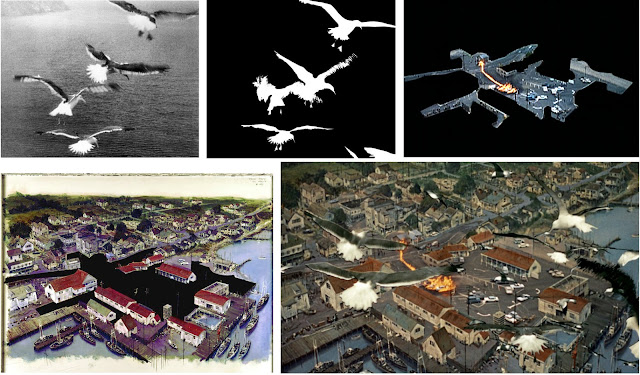

Albert was highly productive at Universal and it wasn't long before the front office knew they were onto a good thing. It is estimated that he worked on around 150 films and television shows, with a great many not being screen credited. Al had already painted on several movies at the studio before any sort of credit, and the first actual credit was an odd one as 'Pictorial Designs by Albert Whitlock' for Alfred Hitchcock's THE BIRDS (1963) for which he painted some 13 mattes. THE BIRDS sealed Al's creative cache with Hitchcock, who would use Albert's services on all of his subsequent pictures. The pair hit it off without question, both being Londoners and of a similar background, not to mention a very junior Whitlock having worked on 3 or 4 of Hitch's very early British films.

Albert was highly productive at Universal and it wasn't long before the front office knew they were onto a good thing. It is estimated that he worked on around 150 films and television shows, with a great many not being screen credited. Al had already painted on several movies at the studio before any sort of credit, and the first actual credit was an odd one as 'Pictorial Designs by Albert Whitlock' for Alfred Hitchcock's THE BIRDS (1963) for which he painted some 13 mattes. THE BIRDS sealed Al's creative cache with Hitchcock, who would use Albert's services on all of his subsequent pictures. The pair hit it off without question, both being Londoners and of a similar background, not to mention a very junior Whitlock having worked on 3 or 4 of Hitch's very early British films.

When compared with dupe matte shots, that were the most commonly utilised method for many years at all of the other major studios, the fidelity of the Whitlock latent image composite just stood out in a class of its own.

When compared with dupe matte shots, that were the most commonly utilised method for many years at all of the other major studios, the fidelity of the Whitlock latent image composite just stood out in a class of its own.

One of the last films that Al worked on as a Universal employee was GREYSTOKE. Bill and Syd would wrangle a deal with the studio to maintain the facility and it's equipment which they would pay a rental on under the banner of Illusion Arts - a company name already trademarked by Bill as part of his side interest in stage magic (more than just an interest... a true passion, according to Syd, along with watches and old clocks), This arrangement only lasted about a year with the decision to find some real estate to call their own, Illusion Arts moved to a new suburban home, near to John Dykstra's effects house Apogee, and another specialty house Grant McCune Miniatures. Universal did a sweetheart deal on all of the old Whitlock equipment, cameras, optical printers and so forth whereby Dutton and Taylor got what they wanted at a bargain price.

One of the last films that Al worked on as a Universal employee was GREYSTOKE. Bill and Syd would wrangle a deal with the studio to maintain the facility and it's equipment which they would pay a rental on under the banner of Illusion Arts - a company name already trademarked by Bill as part of his side interest in stage magic (more than just an interest... a true passion, according to Syd, along with watches and old clocks), This arrangement only lasted about a year with the decision to find some real estate to call their own, Illusion Arts moved to a new suburban home, near to John Dykstra's effects house Apogee, and another specialty house Grant McCune Miniatures. Universal did a sweetheart deal on all of the old Whitlock equipment, cameras, optical printers and so forth whereby Dutton and Taylor got what they wanted at a bargain price.