OPTICAL EFFECTS & MAGICAL MOMENTS

|

| Frank van Der Veer |

I've been away in Japan for the past three weeks or so for a wedding and some first rate tourism, though whilst in foreign lands I've had today's blog post in mind. In a slight departure from my standard matte painting survey, we'll be taking a long overdue and thoroughly deserved look into the world of traditional photo-chemical optical effects, with a somewhat staggering array of great imagery from a century of optical printer wizardry in addition to profiles on a number of the key exponents from the under appreciated and mostly closeted away world of

The Optical Printer. In today's cinema, where relentless, hyper-kinetic and often pointless IMAX scaled visuals are demanded as an absolute prerequisite by both the film maker and the target audience, weaned on mind numbing music videos and X-Box, it's such a pleasure to actually

engage with the trick shots of old, before a time of Apple Mac's, Silicon Graphics workstations and binary data, where the creation of the typical optical effect was often a long and complicated 'hands on' as well as 'eyes on' procedure requiring often multiple rolls of film, special lighting and filtration 'recipes', line ups requiring endless patience and skill, highly sensitive film processing, endless wedge tests and, most importantly, necessitating precision built specialist photographic tools and optics that only a select few could operate and successfully bring all of the elements together in as clean a union as possible with the technology available for any given shot.

I've always had a passion for old school optical effects mainly down to the fact that I just know how hard it was for these guys to make it all come together, where so many things could (and often did) go wrong during the delicate photo-chemical-mechanical procedure, thus requiring an entire retake, or often many retakes in fact, from scratch in order to gain a satisfying marry up of each strip of 35mm or 65mm film. There were no 'undo' buttons nor 'layers' which could be quickly thumbed through in order that corrections be made to a particular element. The optical process as it was prior to the move over to digital, was a slow, methodical and, possibly to some, unbelievably tiresome process. I have great admiration for the folks celebrated here today and the wonders that they achieved. Noted VFX cameraman Bill Taylor told me he doesn't miss the old days one little bit.

|

| Pioneering travelling matte exponent Frank Williams |

Optical tinkering trick work in motion pictures has been going on in some form or another probably as long as the medium has been around, certainly as early as the 1910's. Very early experiments consisted of simple double exposures - a hold over from still photography techniques for several decades from around the mid 1850's or so. Early exponents in motion picture camera wizardry were European pioneers such as Frenchman Georges Melies and the German cinematographer Guido Seeber where audiences in the early 20th Century were treated to scenes involving multiple exposed superimpositions amid fanciful narratives. American pioneers such as Edwin S.Porter produced some of the first known in camera split screen composite shots as far back as 1903 on THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY. Cinematographers such as Paul Eagler, Louis Tolhurst, Frank Booth and Norman Dawn made important inroads into photographic trick shot processes, with key figures such as Frank Williams and Carroll Dunning, individually of each other, making such significant developments in composite optical cinematography that the principle of the technique - in particular the Williams technique - would prove a vital special effect staple for years to follow.

The Williams as well as the Dunning methods were somewhat limited in range but at a time when rear process projection wasn't feasible the competing travelling matting techniques were readily sought after by studios throughout the 1920's and far into the 1930's. Improvements and adaptations of the processes would see cleaner finished composites over time, though not without a number of additional photographic steps being required.

RKO's Lloyd Knechtel, Linwood Dunn and Cecil Love would further refine optical printing processes to a point where renowned film maker and actor Orson Welles once stated that "The optical printer is the best train set a boy could ever play with" (I think that's the quote, or something near to it).

Effects industry luminaries such as Irving Ries, Paul Lerpae, Roswell Hoffman, Hans Koenekamp, Donald Glouner, Robert Hoag, Bill Taylor and Clarence Slifer are discussed and their work illustrated.

|

| British optical expert Roy Field |

Across the Atlantic in England optical printing and travelling matte technology was developing and being refined by leading industry figures such as Vic Margutti at Rank Studios, especially with the yellow backing sodium vapour system where much refinement in pulling mattes from previously problematic artifacts such as water, fine hair and reflective surfaces could be put into practice with excellent results. Other important names in the application of optical printing and composite photography in the UK were George Gunn and Doug Hague who did miraculous work on some of the Powell & Pressburger ballet pictures . Bryan Langley and his assistant Reg Johnson were also in demand when it cane to shooting and assembling optical composites, with Langley having a very long career, largely at Pinewood. One of the newer breed of British optical men was Roy Field who started off in the 1950's with Les Bowie and Vic Margutti before branching out.

In todays article I've assembled a mountain of, hopefully, illuminating material from a wide range of films that cover the whole gamut, from silent era trick shots, various travelling mattes and the variations therein, split screens, optical manipulations, twin effects and of course lots of great effects animation, all from a wide variety of films, some classics and some way at the other end of the spectrum. A number of frames have been collected from high resolution BluRay sourses so they look better than ever. So with that I hope you enjoy this selection.

Pete

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

|

| Two key identities in early optical cinematography were Hans Koenekamp who came to Hollywood in 1911 as a projectionist, becoming a camera operator in 1913 on Mack Sennett comedies. Koenekamp embarked on a massive visual effects career, primarily with Warner Bros and it's foreunner First National from around 1924. Effects director Byron Haskin once called Hans "the greatest effects man of them all". Hans worked non stop on photographic effects through to the late 1950's, with his personal best showcased in the 1947 Peter Lorre picture THE BEAST WITH FIVE FINGERS. Hans passed away in 1992 at the ripe old age of 101. Also shown here is veteran optical cameraman Vernon Walker who, in addition to a few years at First National-Warners and Columbia, would lead the special photographic effects department for RKO up until his untimely death in 1948, with KING KONG and CITIZEN KANE being but two of Vernon's biggest effects projects. |

|

| The optical and matte department at Hal Roach Productions, 1937, as headed by veteran Roy Seawright. Shown here amid the optical printers and bipack camera gear are optical man William Draper, process cameraman Frank Young and matte painter Jack Shaw. |

|

| One of the true legends of optical composite effects work was Irving G. Ries, another of Hollywood's true old timers whose very long career for Metro Goldwyn Mayer spanned some thirty years. Among the many standout pictures Irving added his special magic to were Fred Astaire's amazing dancing shoe set piece from THE BARKLEYS OF BROADWAY (1949), the remarkably intense oil well inferno from BOOM TOWN (1940) and the unforgettable ANCHORS AWEIGH (1945) with Gene Kelly going one on one in a wonderful dance routine with an animated Jerry the Mouse. |

|

| Another old time optical cameraman was Paul Lerpae who headed Paramount's optical unit for near on 40 years. Lerpae provided Oscar winning composite photography for WAR OF THE WORLDS (1953), THE TEN COMMANDMENTS (1956) and SPAWN OF THE NORTH (1938) among many other films. |

|

| Perhaps no other name can be as closely associated with the technical development and refinement of optical printing technology than Linwood Dunn (shown here at left, with RKO's head of special effects, Vernon Walker on the right). In 1929 Dunn trained in optical cinematography under then RKO photographic effects chief Lloyd Knechtel and made important contributions to a great many motion pictures made by the studio, especially Orson Welles' CITIZEN KANE (1941) before branching out in 1957 as an independent effects operator with the company Film Effects of Hollywood along with longtime vfx associate Cecil Love and business partner Don Weed. It is generally accepted that Dunn was responsible for the refinement, sophistication and manufacture of what became known within the industry as The Optical Printer, elevating the potential significantly from what were largely 'Rube-Goldberg' home made units contained in a few Hollywood studios, capable only of fairly rudimentary film effects. |

|

| Clarence Slifer, shown here at left in the MGM optical unit with his assistant Dick Worsfold, was another of those optical 'magicians' recognised by many of his peers to be ahead of his time in not only understanding the technology and it's potential, but also capable of constantly evolving the science of optical effects cinematography. Slifer started in visual effects back in 1932 at RKO Radio Pictures and worked on films such as KING KONG (1933) and THE LAST DAYS OF POMPEII (1935). Clarence's big chance to prove himself and take visual effects several steps further would come about when he joined Jack Cosgrove at Selznick International Pictures in 1936, where entirely new demands were put before him as the fledgling, small studio embarked on elaborate Technicolor pictures such as THE GARDEN OF ALLAH ((1936) and the massive GONE WITH THE WIND (1939). Slifer would continue on as director of all special effects photography at Selznick right on through to the closure of the studio in the late 1940's, from where he would take on similar positions at Samuel Goldwyn, Fox and Warner Bros (reuniting with old friend Jack Cosgrove)before settling into an enviable role at MGM for the remainder of his long career. |

|

| Universal Studios' resident photographic effects man, David Stanley Horsley shown here with special camera rig filming the famous Universal 'earth' globe for an effects sequence in THIS ISLAND EARTH (1955) |

|

| Disney Studios chief of photographic effects, Ub Iwerks (left) with longtime optical cameraman Bob Broughton. |

|

| A much simplified diagram of the Disney Studios preferred travelling matte technique, the sodium vapour beam splitter. |

|

| A good example of flatbed effects animation, presumably on an Oxberry animation stand, at the highly regarded specialist production house, Graphic Films with, in this case, a Venus probe in orbit effects shot in progress. |

|

| Graphic Films' Ray Bloss is shown here operating the animation camera. |

|

| Technician Jon Alexander lines up ILM's aerial image optical printer. |

|

| Industrial Light & Magic made major inroads into optical composite photography at a time when most studios had mothballed their in house optical process departments. It was 1976 when George Lucas' STAR WARS project clearly required more in the way of composite shots than had previously been possible with conventional camera and optical printing systems. The highly specialised printer shown here, built by ILM, the Quad Printer - a unit equipped with four projectors and a complex beam splitter, instead of the usual one or two projectors - didn't come into being until some years after STAR WARS, the effects house constantly upped the ante in the field of special opticals, effects animation and ingenious twists on existing visual capabilities, often to astonishing effect. Shown at top left is ILM's John Ellis, a key technician involved in improvements and technical advances in optical composite work. |

|

| ILM optical line up technician Ken Smith on the Quad Printer, set up in what appears to be 8 perf VistaVision format. |

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

A JOURNEY THROUGH THE MAGICAL WORLD OF THE OPTICAL EFFECT...

|

| Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (1968) set the benchmark for decades to come in superlative special photographic effects. The now famous time gate sequence shown here was largely created through inventive (and time consuming) slit scan streak photography of flat, backlit artwork by combining movement and long exposures on a special camera rig. Co-Effects supervisor Douglas Trumbull devised the then state of the art effects showcase |

|

| The generally unsatisfactory sequel, 2010 (1984) featured impressive miniature and optical composite work supervised by Richard Edlund and his Boss Films. |

|

| Disney's 20'000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA (1954) was a delight, both as an effects vehicle, and as sheer entertainment. Many effects shots abound, with some wonderful animated elements added in such as the schools of fish shown passing the Nautilus in several shots. |

|

| The sinking of the ship from 20'000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA is one of the best effects sequences in the film, with excellent miniature work supplemented by beautifully convincing cel animated streams of rising bubbles as well as a thunderous explosion, also added optically. Joshua Meador and John Hench supervised the animated effects. |

|

| Mention must be made of the contribution of the iconic Maurice Binder and his many memorable motion picture main title sequences, especially a dozen great James Bond pictures. Binder relied heavily upon multi-layered optical composites that cleverly integrated the overall flavour of the particular film. Interestingly, while shooting the titles for the 007 film YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE, the excessive lacquer in the nude model's hair apparently ignited under the heat of the studio lamps, to the horror of the many 'suits' in attendance, who oddly, always seemed to be on the stage whenever Maurice had his harem of nude title girls going through their routines. |

|

| Universal made it's mark with a whole catalogue of technically amazing 'Invisibility' pictures, dating right back to the early 1930's (more on those later in this blog). Most of the invisible gags for these shows were devised by the great John P.Fulton, with his long time assistant David Stanley Horsley assuming the reins once Fulton quit the studio. For ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET THE INVISIBLE MAN (1951) Horsley and career Universal optical man Ross Hoffman creating a number of great shots which work a treat for the comic duo. |

|

| From the same film, one of the many amazing transformation opticals typical of the style that Universal has cornered the market with in many films over two decades - and fifty years before Kevin Bacon's HOLLOW MAN. |

|

| An individual frame from the above transformation. My former, long career in the field of Human Anatomy & Pathology gives this sort of shot a definite 'nod' of approval. |

|

| At the conclusion of A&C MEET THE INVISIBLE MAN our hapless Lou re-integrates, though the lower half of his body is on backwards. |

|

| Paramount's 1933 ALICE IN WONDERLAND employed a nifty optical where young Alice is stopped in her tracks by rapidly changing scenery that reveals the way to The Mad Hatter. Gordon Jennings was effects supervisor. |

|

| People either love or hate director Ken Russell. I like his work and think his film of Paddy Chayefsky's ALTERED STATES (1980) was, after the monumentally brilliant THE DEVILS, probably his best work. Tons of jaw dropping optical work overseen by New York based Bran Ferren, with West Coast suppliers such as Peter Donen's Cinema Research Corporation assembling a great many of the 200 odd blue screen composites. Robbie Blalack and Oxford Scientific Films were also involved. John Dykstra was initially assigned as effects provider but, along with others connected with the much troubled production, found himself out of a job before long. Amazing film. |

|

| More superb effects animation from ALTERED STATES. |

|

| Part of the dazzling effects laden finale from Ken Russell's ALTERED STATES where special make up suit fx by the legendary Dick Smith are integrated with Bran Ferren's special photographic effects work to maximum effect. |

|

| Actress Blair Brown, entirely concealed within a Dick Smith built head to toe 'cracked' foam latex suit, onto which highly reflective 3M front projection material was applied. Optically colourised footage of plain boiling water was then projected onto the surface of the suit to give an incendiary appearance. Bran Ferren manipulated the shots with additional graduated mattes for glow and to create a heat ripple effect. |

|

| Although I try to avoid non-traditional effects work here, this sequence is in part computer generated by Bran Ferren, that is, the swirling, ever changing texture of William Hurt. I believe the shot was matted and composited optically as best I recall. |

|

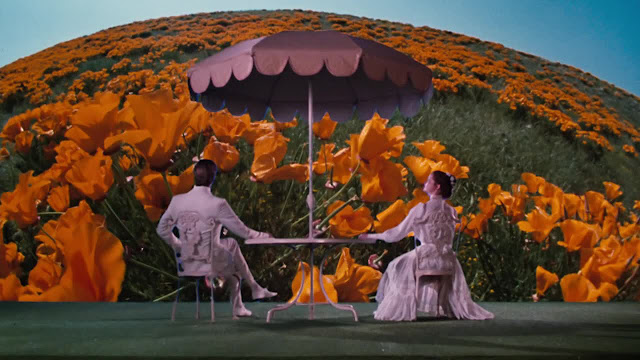

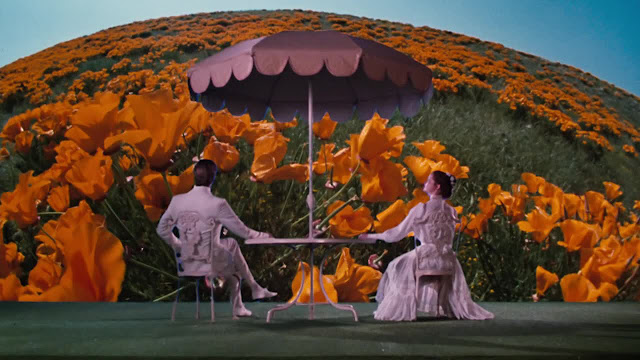

| Surely one of the most fondly remembered visual effects sequences of all time is this utterly delightful 'Dancing Shoes' show stopper from the Fred Astaire musical THE BARKLEYS OF BROADWAY (1949), with resident MGM optical wizard Irving G. Ries pulling out all the stops in assembling this set piece. |

|

| Fred is pure magic even on his own, with Ries' added footwork being the proverbial cherry atop the cake! |

|

| Optical trickery par excellence whereby a

number of dancers clad in black leotards performed on a black draped set

minus Astaire with Ries pulling mattes and compositing against Astaire

dancing on the same set with black drape removed. Additional hand

animated cels were employed to patch up portions of the shoe performance

where the black clad performers accidentally passed in front of one

another, thus obscuring the shoes momentarily, and these are visible in

the circle dance portion shown above. |

|

| Creepy dose of Poe-esque wierdness, THE BEAST WITH FIVE FINGERS (1946) sees Peter Lorre confronted with a piano concerto from a pair of disembodied hands. Superlative photo effects work here, supervised by William McGann and shot and composited by Warner Bros legend, Hans F. Koenekamp. |

|

| I've a soft spot for the films of low budget auteur Bert I. Gordon, with BEGINNING OF THE END (1957) being a bit of a hoot as far as big arsed grasshopper apocalypse sagas go. I admire Bert for what he tries to achieve given the limited means at his disposal. Although many of the effects shots fail, there were a number that worked pretty well, all things considered. Lots of travelling mattes and photo cutouts with crawling insects. Lead man Peter Graves almost makes us believe it all! |

|

| Back to Fred Astaire again, and this time for THE BELLE OF NEW YORK (1952) there's a great, lengthy sequence where our Fred dances up off the ground and along the edges of rooftops, teetering flagpoles and suchlike, with as much grace as he does on the dance floor. Complex multi element sequence comprising much matte art and extensive blue screen travelling matte work, with Fred even bouncing off a bunch of matted out mini tramps as he bounds from flagpole to flagpole. Irving G. Ries figured the tech sequence out and assembled it on his optical printer beautifully. |

|

| THE BELLE OF NEW YORK - Warren Newcombe matte of city and park, a small live action street set, separate element of Astaire dancing on a partial set, all matted together. |

|

| Final scene from THE BELLE OF NEW YORK has our two lovers magically transform into their wedding day best finery, courtesy of Irving Ries optical printer. |

|

| The popular British comedy, THE BELLES OF SAINT TRINIANS (1954) has star Alistair Sim play a dual role, which Wally Veevers combined smoothly to good effect. |

|

| One of Robert Hoag's numerous blue screen travelling matte shots from MGM's BEN HUR (1959) with the background ocean battle being an elaborate miniature set up by Arnold Gillespie in the backlot tank, and photographed by visual effects cameraman Harold Wellman. |

|

| For BENEATH THE PLANET OF THE APES (1970), Art Cruickshank manufactured several hellish visions for effects supervisor L.B Abbott using much optical printing trickery. |

|

| John Wayne's overlooked BIG JAKE (1971) has some great, though subtle effects work in it courtesy of Albert Whitlock. This electrical storm looks great on screen, combining matte painting, cel animated overlays with a location plate. |

|

| Alfred Hitchcock loved to utilise camera trickery, and what's more, he completely grasped and understood each of the processes available to the film maker and knew how best to use same. For THE BIRDS (1963). Although a Universal picture, Hitchcock obtained the services of Disney's Ub Iwerks to oversee the hundreds of process shots. To handle the very large number of effects shots, Iwerks farmed out several sequences to the photographic effects departments of other studios. While most of the composite photography was executed at Universal by visual effects cinematographer Ross Hoffman, the school attack sequence (shown at top) was handed over to L.B Abbott to assemble at 20th Century Fox. Some other opticals were assigned to Robert R. Hoag at MGM. |

|

| An especially frightening effects sequence from THE BIRDS where multi element mattes have been assembled on the optical printer to accommodate the sheer depth of the action. On the freeze frame I've selected here bleed through of the printed in bird elements is evident, though never so in the actual motion sequence. |

|

| Another extremely effective multiple element matte composite. |

|

| With Ub Iwerks' background being largely associated with the yellow backing sodium vapour matting system employed exclusively at Disney, certain shots in THE BIRDS utilised that process. |

|

| The centerpiece moment from THE BIRDS is this eerie aerial shot. Actual gulls were photographed off Catalina Island, isolated as hundreds of hand drawn mattes by Universal rotoscope artists Millie Winebrenner and Nancy van Rensaellar, with effects cameraman Ross Hoffman doubling the high contrast 'bird' mattes over Albert Whitlock's painted town. |

|

| Throughout the 1970's and into the 80's, American television viewers were treated to the spectacular visions of Robert Abel and Associates in the form of various out of this world tv commercials and logos. Abel's were in a class of their own in as much as technical ability and, presumably, heavy budgets courtesy of their clients that would afford such spectacle on the small screen. |

|

| Another example of the visionary commercial magic of Robert Abel and Associates probably from the late 1970's which nowadays we all take for granted, and even find quite tiresome as we find ourselves bombarded with endless computer graphics and eardrum shattering noise. |

|

| Fred Sersen was one of 20th Century Fox's biggest assets. His photo effects department saw no boundaries when it came to creativity and delivering wonderful special effects shots. For Tyrone Powers' 1940 pirate adventure THE BLACK SWAN Sersen meticulously matted in live action extras and stunt players onto the deck of Anthony Quinn's ship (a miniature) while the moving ship plowed bow first onto the rocks, with the masts crashing down on the fleeing stunt guys. Very well accomplished, with some stunt guys even matted jumping over the side, some crushed by the miniature mast with some guys visible behind the mast as it falls onto some pirates. Sersen would use this 'real people in miniature settings' gag on several films over the years, gaining Oscar nominations for that work on several occasions. |

|

| For THE BATTLE OF BRITAIN (1969) Wally Veevers would create a vast squadron of German dive bombers over London by way of his home made (built in his garage) If I recall correctly, Wally made

this shot on his so called 'sausage machine' - a home built contraption

comprising gears, servos and glass plates - a device he made for

Kubrick's 2001 the year before. FX cameraman Martin Body said that all

of the German dive bombers were (if I'm not mistaken) photo cutouts,

mounted in several layers on successive sheets of glass, with each layer

or sheet of planes gently controlled in a realistic x or y axis so that

there was a natural independent sway to each of the aircraft in flight

and the whole thing composited against an aerial 2nd unit plate of

London, to great effect. |

|

| Nominated for best special effects in 1940 was the Shirley Temple vehicle THE BLUE BIRD which, among other things, has a ripper of a forest fire where our cast are expertly combined optically with an outstanding large scale miniature fire to often terrifying effect. Fred Sersen was in charge. |

|

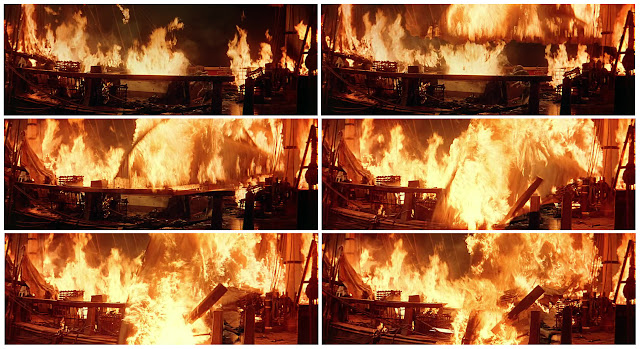

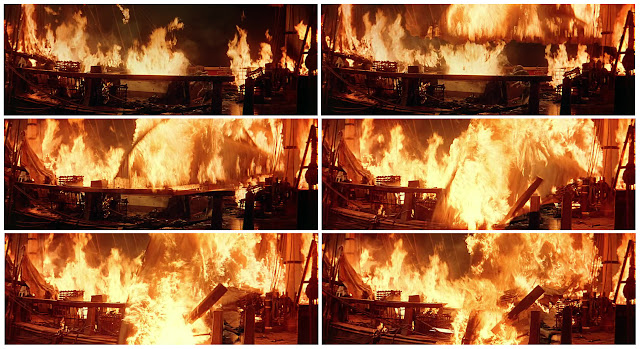

| While we're on gigantic fires, this one is one of the best optical/physical effects sequences ever. It's from the Spencer Tracy-Clark Gable oil drilling picture BOOM TOWN (1940). All round excellent effects, from the Newcombe mattes, Gillespie miniatures and mechanical effects, through to these chilling composites by Irving Ries where hapless firefighters are enveloped in a raging inferno. |

|

| BOOM TOWN - The out of control conflagration sweeps across the main characters fire safety shield. I don't know if the fire was hand rotoscoped or photographed straight and processed into high contrast mattes, but it works very well. I'm pretty sure this film received an Oscar nomination for these scenes. |

|

| In an era where we are drilled to the point of near hari-kari by pointless, over designed, over directed and over extended visual effects, it's always an utmost pleasure to sit back and enjoy the near pedestrian, leisurely pace of a film like BLADERUNNER (1982) where the visuals are no only so perfectly designed and executed, but used so sparingly. Douglas Trumbull initially supervised the effects though when his own film BRAINSTORM got the green light, David Dryer and Richard Yuricich took control and saw the opticals and composites through to their completion. |

|

| One of my favourite effects shots from BLADERUNNER. Mostly miniature with projected overlays and excellent front light/backlight matting of flying vehicles - Trumbull's favoured modus operandi for clean results. Without question one of the finest visual effects films of all time, with each and every visual effects shot suitable for framing, and as I've said here before, one vastly overlooked in the VFX Oscar category that year in favour of the insufferably sweet ET. I've just returned from Japan and I can testify that walking the busy streets of Osaka at night resembled a scene out of BLADERUNNER... Uncanny! |

|

| Still a cool 50's sci-fi flick, THE BLOB (1958), the low budget cult classic has some nifty effects shots such as this. Bart Sloan was the photographic effects man on the show. |

|

| Doug Trumbull's BRAINSTORM (1983) was an ambitious, not entirely successful, though certainly provocative sci fi drama. The special photographic effects by Entertainment Effects Group were, simply put, monumental, both in terms of narrative scale on screen and the massive photographic complexities encountered in producing many of the shots. The requirements for some of the optical composite shots were mind boggling in terms of originally photographed elements and the volume of those elements once multiplied and combined as one overall shot. |

|

| Visual effects supervisor Alison Yerxa went all out in designing BRAINSTORM's heaven sequence. Each of the hundreds of dainty angels were in fact just the one solitary performer, a dancer named Susan Kampe, who was filmed at 96 fps while dancing at night around the Entertainment Effects Group parking lot. Optical fx man Robert Hall then combined the numerous takes on the EEG optical printer to present around 140 'angels' for each of the shots. |

|

| More frames from the utterly exquisite heaven sequence, with flawless combination of the many, many individual elements to form one of the best visual effects sequences in years. Effects cameraman was Dave Stewart - a veteran of other Trumbull shows such as CE3K. Optical line up, so essential in any printer job, was handled by Michael Backauskas. The film really should have been considered for Oscar contention in the effects arena, though, as we all know, a non successful film will never get any Oscar consideration. |

|

| Universal's 1931 classic FRANKENSTEIN, has this well hidden photographic effects shot at the conclusion of the film where the Karloff hurls Colin Clive form the top of a burning windmill. Only the lower part of the tower is actual, with the rest of it being a mechanised miniature. The figures of Karloff and the falling Clive have been added in by travelling mattes. John P. Fulton was effects man on this and scores of other Universal monster pictures. |

|

| For the sequel, BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1935), Fulton once again came through with some astounding optical effects work where several glass jars containing live tiny people are displayed. In this scene above one of the escaping miniature people is recaptured with tweezers and placed back in his jar. This is a remarkably competent effect, with the tiny character seen struggling, in what is clearly the actual actor matted in, passing across the screen as opposed to a doll or something equally fake that other less confident technicians might have resorted to. |

|

| More stunning optical work from BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN. |

|

| Popular English comic Norman Wisdom was never one known for subtlety. In THE BULLDOG BREED (1960) our unfortunate Norman somehow self inflates (I forget how) and in true Tex Avery style is punctured and takes off at great speed across the water. 'Norman' is a completely cel animated element consisting of sequential drawings, composited over what I suspect must have been a small speedboat, to create the appropriate wash and spray. Roy Field handled the optical work while Cliff Culley painted the long shot shown at lower right. |

|

| Steven Spielberg's CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE 3rd KIND (1977) was a big effects show, with much of the key visual material held for the latter act of the film. For these scenes involving the huge alien Mothership, effects animator Robert Swarthe spent a considerable amount of time meticulously animating rapidly changing arrays of light 'code' as backlit artwork that would be later composited over an interior set, with in some cases, matte art by Matthew Yuricich and miniatures by Greg Jein. Marvellous scene, and so well done by all concerned - especially John Williams. |

|

| A guilty pleasure of mine is the kind of cool little 'death-on-four-wheels' chiller THE CAR (1977). Sadly, this shot is a major spoiler, as the homicidal black car is demonic to say the least, and may in fact have been driven by The Devil himself! Albert Whitlock supervised the visual effects, with optical photography by Bill Taylor and Dennis Glouner. A fantastic, nightmarish vision of the Devil

himself, carefully articulated and chillingly brought to life in an

unforgettable sequence that'll make your skin crawl. Bill

Taylor told me the scene now makes him wince as much time has passed and technology has improved. Bill kindly described to me in detail just how this wonderful optical

was achieved, with, in essence big naptha fires and slow motion flame thrower elements against white Mole smoke

shot against black in our studio, with the facial features (as such) constructed as a black cloth

covered wire armature, articulated so that the 'mouth' could move. It was then

set alight and photographed at 120 fps through a distortion glass with

much optical manipulation. The effect was never finished as they just

ran out of time. Earlier incarnations were more subtle - perhaps too

subtle as preview audiences didn't 'get it'. Bill joked to me that he

felt the next logical step might have been to sound a car horn on the

soundtrack and have a flashing title that would read 'Big Demon Face' appear on the screen. Personally I think it's a fantastic effect, and like it even more now that Bill has elaborated upon it. |

|

| A great single frame of the very pissed off Devil from THE CAR. The facial features were interesting, with a black cloth wrapped on an articulated wire armature with the cloth soaked in napthalene, similar to lighter fluid, which gave off a nice yellow flame which when set alight was blown with a fan. Bill recalled to me that it all dripped little drops of flaming naptha, though even though the face was of a pretty good size, the flames still looked to 'big', so they hit upon the notion of shooting them through a moving distortion glass in order to break them up. Bill told me that in his opinion Leonard Rosenman's score helped here alot, which I'd agree to. |

|

| An odd choice to include here possibly? Mike Nichols' brilliant CATCH 22 (1970) has this seminal moment when one of the principle characters is cut in half by a deliberately flown low level airplane. The actual collision and moment of splatter was achieved with a dummy specially rigged by the practical effects crew, and a stunt pilot. Now, where this gets interesting is the subsequent shot where the disembodied lower half of the guy slowly turns and collapses into the sea in almost cartoon fashion. I've read two different accounts of this shot and one stated that the actor concealed his upper body by holding a special 3M shield of front projection material which reflected the sky, thus rendering him 'half missing'. The other account I've read was that Albert Whitlock, who painted a matte on the film, rotoscoped out the top half of the actor in post production. Whatever was done, the shot was an audience grabber back in the day and still packs a punch all these years later. |

|

| Orson Welles' CITIZEN KANE (1941) was a huge visual effects show with virtually every trick shot under the sun. Vernon L. Walker supervised the effects work with Russell Cully as effects cinematographer and Linwood Dunn assembling all of the components of some very intricate shots. One of the many mysterious, almost off kilter optical composite effects in the film is this one which I love where Kane's nurse enters his bedroom. |

|

| Also from CITIZEN KANE is this brief, yet curious multi part shot. Second unit plate of bay and sea, soundstage set at RKO, and for reasons I've never quite comprehended, yet another layer added in as a foreground parrot which serves no valid purpose. Take a look at the bird's eye and you can in fact see right through the bird and out the other side due to matting errors. |

|

| The big, sprawling western CIMARRON (1960) included this quite amazing example of optical printer wizardry. To allow actor Glenn Ford to rescue a small child from the path of an out of control horse, MGM effects cameraman Clarence Slifer locked down the camera on the set and shot the scene in dual takes - one with Ford and the kid, and the other with the runaway horse and disabled rider. The two plates were combined with a soft split, followed by some finely tuned frame by frame rotoscoping on some thirty sheets of glass in the matte department gave just sufficient 'animation' to to place the horses' front legs briefly in front of the actors as well the back legs behind the actors for barely 30 frames. By splitting the scene in two with the soft matte there wasn't any need for Slifer to fully rotoscope Ford and the child for the entire shot, only for the one second or so that the horse galloped over the top of them - or at least appeared to. |

|

| A fairly entertaining little fifties sci fi that unfortunately never pays off. THE COLOSSUS OF NEW YORK (1958) isn't as good as it could have been but has a few okay animated overlays and roto effects by John P. Fulton and Paul Lerpae. |

|

| More from THE COLOSSUS OF NEW YORK |

|

| Again with John P. Fulton we have this George Pal space adventure CONQUEST OF SPACE (1955) directed by former effects man Byron Haskin. The optical work and models are pretty bland and lack creative energy, though maybe fifties audiences found it more of an event. |

|

| As I've mentioned earlier, Fred Sersen was gung ho to break new ground in bringing visual effects up onto the screen. For the Tyrone Power war picture CRASH DIVE (1943) Sersen once again successfully added actors right into extensive miniature battle scenes - on land and on boats - via blue screen travelling matte, the result of which would garner Sersen an Oscar for best special effects. Assisting Sersen were Ray Kellogg and Ralph Hammeras, with James B. Gordon as director of effects photography. |

|

| Without question one of the greatest true life wartime events ever, THE DAMBUSTERS (1954) film is still a rousing account of heroism, daring and self sacrifice for the common good. The destruction of Germany's Ruhr dam was a challenge for the production, though not nearly as much a challenge as it was in reality for the RAF. George Blackwell built many miniature bombers, European countryside and the dams themselves. Future Star Wars DOP Gil Taylor was effects cinematographer for the miniature action sequences, with the many blue screen shots handled by Vic Margutti. The shots shown here are interesting as the actual bombing run POV's are mobile aerial shots and with the actual explosions themselves being separately filmed, optically manipulated and rotoscoped in elements of large crashing waves, shaped by rotoscope artist Ronnie Wass to resemble huge detonations in water. Presumably the production chose this interesting route instead of actual squib charges in the model dam in an effort to give as much weight as possible to the explosion. |

|

| DAMBUSTERS - the mission's moment of success. |

|

| Reverse angle of the explosion and break up of the dam. As an aside, the last surviving real life Dambusters pilot, New Zealander Les Munro, died just a couple of months ago. |

|

| Even when I saw this at the theatre in 1977 I never bought those darned DAMNATION ALLEY scorpions. An effects heavy film that was out of it's league. William Cruse and Margot Anderson supervised the effects work, with optical compositing farmed out to other effects providers such as Film Effects of Hollywood. The scorpions were live and filmed in natural sunlight on blue plinths. |

|

| I'd be interested to know how easy it was - or wasn't - for MGM optical man Irving Ries to pull clean mattes off Esther Williams whilst swimming underwater for DANGEROUS WHEN WET (1953) |

|

| One of the greatest effects showcases of all time, and one shamefully overlooked by the Motion Picture Academy, Disney's DARBY O' GILL AND THE LITTLE PEOPLE (1959). Filled to the hilt with some of the most imaginative effects work to date, DARBY is a tour de force of technical achievement. From the incredible in camera perspective gags and Schufftan shots, the beautiful matte art and delightful John Hench effects animation as shown here. |

|

| DARBY O' GILL is also notable for it's quite frightening ghostly apparitions, achieved through special solarization of the colour motion picture negative to jarring effect - for a Walt Disney film! |

|

| Paramount trick shot specialists Devereaux Jennings and Paul Lerpae accomplished some good 'twin' effects for the Olivia De Havilland film THE DARK MIRROR (1946) |

|

| Fox economised for the film D-DAY THE SIXTH OF JUNE (1956) with German artillery and bunkers being strictly matte art, with the muzzle flashes and explosions being well done cel animated effects. Ray Kellogg was effects chief. |

|

| Robbie Blalack's Praxis Film Works supplied the requisite destruction for the apocalyptic made for tv drama THE DAY AFTER (1983). |

|

| Flash frames of nuclear destruction from THE DAY AFTER. |

|

| Bette Davis plays twins of differing temperaments in Warner's 1964 drama DEAD RINGER. Some ingenious split screens |

|

| Dream Quest Images created this missile trajectory and explosion for the dire Chevy Chase vehicle DEAL OF THE CENTURY (1984). Note the reflective glow across the water... nice. |

|

| The James Bond adventure DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER (1971) had a number of Albert Whitlock matte paintings and Wally Veevers model effects. This scene where a Red Chinese nuclear missile battery gets wiped out was a substantial Whitlock matte painting with nuclear flash element. The stunt man is shown performing in front of a light grey painted screen outdoors in natural light. I asked Bill Taylor about this shot and he told me "The flaming guy was roto'd in with the white cel system. The backing was originally neutral grey, the best compromise for roto". |

|

| Although a somewhat uneven film effects wise, DRAGONSLAYER (1981) featured some dynamic effects animation and optical gags to compliment the excellent new Go-Motion process as shown here. ILM did the visual effects work. |

|

| A jaw dropper of an opening shot (more frames below) from the medium budget little sci-fi flick DREAMSCAPE (1984), where a character is haunted by the prospect of nuclear war. Peter Kuran at VCE was engaged to produce this and many other great optical and miniature effects shots that still look good today. |

|

| The horrific latter stages of the nuclear blast involved multiple printing combined with fire elements, with the woman carefully rotoscoped down to a skelton, and eventually vapourised. The brief sequence would combine nearly sixty separate elements on Kuran's optical printer. The sort of shot that back in the old VHS days I just had to rewind and watch mutliple times - and so apparently did many others as the tape always seemed to have glitches during this (and other cool) fx shots. |

|

| Fox's big budget Biblical epic, THE EGYPTIAN (1954) was packed with matte shots, though also had a few interesting little opticals as well. This one of a pouncing lion, added via travelling matte, is one such shot. Ray Kellogg was head of the effects department, with L.B Abbott and James B. Gordon among the effects cameramen. A young Frank Van Der Veer was there then too, presumably in opticals. |

|

| George Lucas' EMPIRE STRIKES BACK (1980) was a rollercoaster ride of amazing and well assembled optical composite shots. The ILM optical department really had their hand full with the roster of shots needed for this film. |

|

| Paramount's ELEPHANT WALK (1954) was an unlikely film to feature optical effects, yet it had quite a number of really interesting effects shots throughout. The great, though difficult, John P. Fulton oversaw all of the effects work including this multi part optical composite to show a vast herd of elephants. Effects cinematographer Irmin Roberts shot the live action plates which optical man Paul Lerpae combined - with some Jan Domela matte art - on his optical printer to expand what wasn't possible to shoot, first hand. |

|

| Another interesting shot from ELEPHANT WALK has Peter Finch and Elizabeth Taylor flee for their lives as a burning building drives an angry herd of elephants toward them. The collapsing building is a large miniature, built by Ivyl Burks, which in turn was used as a plate for the travelling matte composite with the actors and foreground set. Works well. |

|

| Universal's medium budgeted super hit, EARTHQUAKE (1974) was a field day for the effects team, with this shot being of particular interest. A backlot street at Universal has been substantially added to with Albert Whitlock's matte art and various smoke and fire elements. The fellow running into camera was rotoscoped one frame at a time so that he could pass over the fabricated Whitlock area of the shot convincingly. Long time Universal roto artist Millie Winebrenner did the work here, with veteran vfx cameraman Ross Hoffman compositing all of the elements as one. Interestingly, several of the shots in the film have gaping flaws in them that one doesn't necessarily pick up first time around. This shot (and a couple of others) inexplicably show large chunks of debris falling 'out' from under Whitlock's matte art - in this case in the upper right corner. Some other shots have debris tumbling behind the matte lines. Roto could have sorted this but the film was a rush job and tighter than usual deadlines meant that release dates had to be met. The film was a huge hit. |

|

| Not really an optical effect but I'll include it anyway as it's my blog and I can do as I please. Roger Corman's THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER (1960) ended with this massive inferno. Virtually all a matte painting (possibly by an uncredited Whitlock?) with the inferno being what appears to be a rear projected plate behind the painting, as it's out of focus a little. Butler-Glouner were officially credited with special effects. |

|

| A unique look at the highly inventive in camera photographic effects created by little known optical artist Herman Schultheis at Walt Disney Studios for the spectacular FANTASIA (1940) |

|

| While matte lines abound, FANTASTIC VOYAGE (1966) is still a wonderfully rousing entertainment some fifty years down the track. Former Disney optical man Art Cruickshank was largely responsible for the many arresting and creative trick shots and optical puzzles that made the film quite a talking piece in it's time. |

|

| The overall effects design is terrific and Cruickshank did what he could with the processes available at the time. Interestingly, it's really only the interiors of the micro sub with matted in backgrounds that don't hold up, while the rest of the photo effects look solid. |

|

| There are far more effects shots in Hitchcock's FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT (1940) than you might think. One of Hitch's absolute gems, this thrilling film hits all the right bases, with Paul Eagler's effects shots being an added bonus. |

|

| Ray Harryhausen's FIRST MEN IN THE MOON (1964) was his only foray into the realms of CinemaScope, thus necessitating a radical rethink on his tried and true rear screen process. The film has a multitude of optical effects, mostly blue screen mattes bringing the cast into the many miniature settings, as well as some nice fx animation and distortion optical gags. I think Vic Margutti may have been involved in the very large number of travelling mattes. |

|

| FLOTSAM (1940) is a film I know nothing about, other than this before and after clip showing a Jack Cosgrove matte with a guy and his mutt doubled into an actual dramatic night skyscape. Probably a Clarence Slifer shot as this was definitely his sort of thing, plus he had a long working relationship with Cosgrove. |

|

| The very strange Paramount musical FOLLOW THRU (1930) was an odd two toned Technicolor film with, among other things, this outrageous musical set piece where a bunch of chorus girls dance themselves up into a frenzy, burst into flames(!) and are subsequently extinguished by firemen who fly down from the clouds! No, I'm not making this up. Bizarre, but well executed, with Irmin Roberts as effects cameraman. They don't make 'em like this anymore. |

|

| As mentioned earlier, I've a bit of a soft spot for Bert I. Gordon, and feel that he does okay with the limited resourses at his disposal. Although I kind of rubbished FOOD OF THE GODS (1976) back in the day when I saw it at the cinema, it actually looks pretty good nowadays. Gordon did all of his own effects work, and, by and large, it's mostly good here. Lot's of clean looking split screen mattes to blend in giant rats with the cast, with in many cases no visible matte line. Some of Bert's split screen shots are in fact excellent, such as the two bottom frames I've selected here. The perspective and placement of camera is spot on, the light is clearly actual daylight for both sides of the split, and it's as steady as a rock. Some of the shots look so good as to suggest original negative held takes, which must have been tricky. |

|

| James Bond titles maestro Maurice Binder made this unusual excursion into actual visual effects with the impressive time warp sequence for the undervalued Kirk Douglas film THE FINAL COUNTDOWN (1980). The optical work was carried out I believe at England's Shepperton Studios. |

|

| A rare photo of what I believe is the effects set up on the old FLASH GORDON serial from the 1930's. As far as I know the serial was produced by a unit, affiliated with Universal Studios, though not the actual studio itself... though I may be wrong? |

|

| The 1980 reboot of FLASH GORDON had quite a lot going for it. It never for one moment took itself seriously and was kind of fun. Some great sets and costumes, a load of hot space gals and the always brilliant Max von Sydow - what's not to like? The many optical effects shots were done by Frank van Der Veer and Barry Nolan. |

|

| MGM's FORBIDDEN PLANET (1956) was a sizable visual effects show with this sequence being of interest. Anne Francis and the tiger were filmed on the same set, though at different times. Instead of a moving split screen, optical expert Irving Ries employed a series of static, soft edged mattes which were plotted one after the other as the tiger walked across the set, followed by the actress. In the two frames above the soft edge is just visible around the animal's hindquarters with part of the tiger fading off. |

|

| FORBIDDEN PLANET's centre piece is the arrival of the monster from the 'ID'. MGM borrowed highly esteemed animator Joshua Meador from Walt Disney for the sequence, and while the concept was okay, I don't think it was successful as a 'creature' by any means and certainly had it's roots in the cartoon realm. The old addage of what you think you can see rather than what can be seen really should have been the way to go here, with just subtle hints of said monster being far more effective. The other peripheral animation effects in the sequence however were great. |

|

| Effects animators included future Art Directors Joe Alves and Ron Cobb, with the overall animation designed by Ken Hultgren. Disney's Art Cruickshank shot the animated sequence, with Ub Iwerks as consultant. |

|

| The early scenes of the unseen monster creeping through the spaceship and getting up to mischief were actually very intense, leading us to be somewhat let down by the eventual materialisation of said beast. The same can be said of a hundred other films such as PREDATOR, where for 70% of the film it's stark terror, and then the guy in the rubber suit just kind of nullifies all that had been built up till then. ALIEN was an exception.... Ridley knew just how much and how often he should show that son-of-a-bitch, and it worked 100%. |

|

| The phenomenal success that was GHOSTBUSTERS (1984) was in part due to Richard Edlund's Boss Films fanciful visual effects and Bill Murray's comic timing. Of all the visuals in the show I most of all loved these crazy Neutron Wands, which, even in the hands of semi-experienced operators as shown above, proved as uncontrollable as a fireman's hose on full pressure! Whimsical design and great fx animation by Sean Newton, William Recinos and Pete Langton. Best line: "Remember, don't cross the streams" ... "Why, what will happen?"... "Something bad". |

|

| More off the wall effects animation that always got a laugh from the packed audience back in '84 |

|

| GHOSTBUSTERS - an ethereal light takes hold of Manhattan. Other animators involved included Les Bernstein, Wendie Fischer and John van Vleit at Available Light. |

|

| The inevitable follow up, GHOSTBUSTERS II (1989) would see a change of effects providers, with Industrial Light & Magic taking the reins. |

|

| GHOSTBUSTERS II - A sense of dread envelopes the city. Great optical shot here. |

|

| Those non-Occupational Health & Safety approved Neutron Wands are at it again, and thankfully the design and execution closely follows the look that Edlund established with the first film. |

|

| David O. Selznick's GONE WITH THE WIND (1939) was probably the biggest effects show to date, and even more so for such a small studio as Selznick International. Under Jack Cosgrove's supervision, effects cameraman Clarence Slifer assembled this amazing pullback shot on his aerial image optical printer. The sky is real, having been photographed as a second unit shot after a spectacular thunderstorm; the view of the Tara plantation and surrounding landscape are matte paintings. The two actors are real and were filmed as high contrast mattes, while the tree is a miniature. Slifer pieced all of these elements together into a seemless and dramatic shot - one that would be repeated with different elements at two other points in the film. |

|

| Throughout the Golden Era the place of the Montage Director was important, with most studios engaging an entire montage unit to design and create transitional sequences and special photographic effects. These montage directors wielded significant creative power and autonomy. For GONE WITH THE WIND Selznick employed MGM's Peter Ballbusch as montage director, for which Ballbusch created this superb transitional montage midway through the story. |

|

| Another of Clarence Slifer's invisible optical shots from the same film. The burning of Atlanta involved numerous optical enhancements such as this view where a burning building (actually the left over Skull Island wall set from King Kong) collapses behind Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh. Filmed separately, and many months apart, the footage of two stunt doubles in the carriage were bi-packed into the inferno footage as high contrast travelling mattes to great artistic and dramatic effect |

|

| Although a film that never knew what it was trying to be, Eddie Murphy's THE GOLDEN CHILD (1986) was a terrific visual effects piece, with a large number of first rate effects shots throughout. ILM really outdid themselves here with solid and spectacular work. For this sequence, actor Charles Dance reveals his true self, in somewhat Dante-esque proportions at that! A remarkable, continuous visual effect involving much miniature work and optical manipulation for what is really a pullback from the depths of hell! Phenomenal shot guys! |

|

| More frames from the above effects shot. |

|

| THE GOLDEN CHILD - a winner for effects buffs. |

|

| A recent photo of former Disney matte painter Harrison Ellenshaw posing with the old Disney optical printer. |

|

| Danny Kaye's HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN (1952) has this splendidly realised optical transition by Clarence Slifer. |

|

| HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN |

|

| The flip side to big name comic duos of the forties such as Abbott & Costello etc were the eccentric Ole Olsen and Chic Johnson who were in a 'class' of their own, and pretty funny to boot. HELLZAPOPPIN (1941) is an utterly insane, out of control, cacophony of sights and sounds, with some outrageous optical effects and gags, such as a character actually picking up a matte painting in one scene and propping it up in order that the action may continue! Anyway, the sequence above is a crazy mismatched body parts gag, where our two stars half vanish with top and bottom halves merging back as one person - though the bottom half is naturally on backwards. John P. Fulton was effects boss here. |

|

| HELLZAPOPPIN top n' tail wackiness. |

|

| Laurence Olivier's very successful HENRY V (1944) had several matte shots by Percy Day though many viewers didn't notice this brief, though time consuming optical effect. Cel animation provided the hundreds of arrows that fly through the air and into the bodies of the opposing army. It's well done, with believable perspective drawing and movement. I suspect that Day would have farmed out this shot, but to whom, I have no idea. |

|

| The Robert Wise picture THE HINDENBERG (1975) was an Oscar winner for it's special visual effects. This shot is of particular interest as a multi-part shot that is totally believable on screen. The shot comprises live action combined with Albert Whitlock matte art, with the truck, flawlessly rotoscoped frame by frame passing in front of the matte painted airship. |

|

| I've always admired this shot from THE HINDENBERG where George C. Scott is blown to kingdom come - be it by accident or his own choice we never discover. I spoke to Bill Taylor about how he achieved this shot: "George

Scott did not want to be hung from wires against a blue screen, and I

can't say I blamed him. So we put him on a bicycle seat, leaning

against a tilting rig covered in black velvet. He could lean back in

some comfort, move his arms and legs freely, and so on. We lit his

highlight side with a white key light, the shadow side with blue light,

gave him a blue necktie, blue socks and painted his black shoes blue.

He found this all exceedingly mysterious. "I don't know what they're

doing," he told a visitor, "but it's got something to do with the blue

tie and the blue shoes." We zoomed him back with a 20-1 zoom lens. The

background consisted of artwork, pyro elements and a fire extinguisher

discharged at the camera. I knew there would be holes in the matte in

the shadows of his jacket and so on, but the thought was to fill in the

holes with roto. Everyone liked the quick pre-roto test where the holes

in the matte gave more definition to the silhouette. So we declared

victory and moved on to the next shot". |

|

| I didn't care for the film, but the effects work for Steven Spielberg's HOOK (1991) by Industrial Light & Magic made it watchable with superb matte art and some beautiful optical composites. The effects recieved a nomination by the Academy that year. |

|

| I've often mentioned this completely off the wall exercise in cinematic insanity - the Japanese horror film HOUSE (1977). I don't think I've ever seen a film with as many opticals in it - and opticals that make no sense what so ever but are just there for the hell of it. An indescribable experience that I whole heartedly recommend to fans of special effects as well as devotees of the outright bloody weird! No English credits as to who did the opticals and extensive matte painted shots. |

|

| Same film... it's as though the production just received a brand new optical printer and desperately wanted to thrash the hell out of the thing as some sort of artistic expression. Above we have a typical HOUSE optical, with a chick being devoured by a grand piano, while being watched by matted in goldfish, and a dangerous looking amount of high voltage. Just when you think you've seen it all folks! |

|

| No, it's not Mick Jagger, it's just another 'moment' from the Japanese flick HOUSE. |

|

| Guns don't kill people...piano's do !!! Enough said. |

|

| I wish I could tell you what's going on but even after 3 viewings I've no idea. My guess is that the optical printer must have exploded by the end of post production. |

|

| HOUSE - optical madness afoot! |

|

| Universal's THE HOUSE OF DRACULA (1945) with a neat transition from cel animated bat to actor as Dracula. |

|

| Frame from below multiple dissolve transformation in HOUSE OF DRACULA. |

|

| HOUSE OF DRACULA with photographic effects by John P. Fulton. |

|

| A name synonymous with high quality production values and visual punch were the New York based firm R/Greenberg and Associates, run by brothers Richard and Robert Greenberg. Mostly responsible for glossy tv commercials such as the one shown here as well as highly regarded work in feature films such as Woody Allen's brilliant ZELIG (1983) and state of the art opticals for PREDATOR (1987) |

|

| The curious though not too bad Blaxploitation film THE HOUSE ON SKULL MOUNTAIN (1973) had some uncredited visual effects shots, namely this matte painted mountain and villa, with some electrifying storm effects. |

|

| Actually quite a bit better than it's name would suggest, I MARRIED A MONSTER FROM OUTER SPACE (1958) had some creepy moments, such as the scene above where successive flashes of lightning reveal our man to be not who we think he is. Not sure if this is an optical or just clever cutting in the edit room, but it works a treat. |

|

| Also from the same film is this effective optical effect by Paul Lerpae of a guy being swept into a forboding black fog. John P. Fulton was Paramount's head of special effects at the time. |

|

| Another effects sequence from Paramount, this time from the Mae West film I'M NO ANGEL (1933) where our star has been composited with an angry lion in his cage during a circus act. Optical cinematographer Paul Lerpae even made the star place her head in the lion's mouth. Effects cameramen Dev Jennings and Irmin Roberts. |

|

| Irwin Allen's popular LOST IN SPACE tv series of the mid sixties was my favourite show back in the day. Rarely short of effects shots, most episodes had something spectacular for a kid to thrive on. L.B 'Bill' Abbott was general overseer of the visual effects, assisted by Howard Lydecker on miniatures. |

|

| Universal seems to be getting quite a solid grounding in todays blog judging by the sheer number of films I've referenced. Here's a great optical from the Jack Arnold film THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN (1957) - a film jam packed with dozens of sometimes complex opticals. This shot is a winner for me as we watch our hero Grant Williams, run across a busy street, barely avoiding an approaching car, rushing under the feet of a passer by and on into the cafe. Excellent travelling matte work here by Ross Hoffman, with precise roto work where Williams dodges the car and the big guy by the cafe door. |

|

| Same film, though the complete lack of any degree of shadow under Williams reduces credibility. |

|

| Another tremendous effects set piece from the same film sees Williams almost trodden on whilst struggling to stay afloat in a flooded basement. Well designed and directed sequence with superb optical composites and additional 'splash' elements doubled in. Really impressive. |

|

| Same film - the fight with the spider. Former RKO effects cinematographer Clifford Stine was overall effects supervisor with Ross Hoffman as optical effects cameraman, Ed Broussard as visual effects editor and Millie Winebrenner handling rotoscope duties. |

|

| Steven Spielberg's INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM (1984) won ILM a well deserved Academy Award for it's many and varied visual effects. I've selected this frame for it's ideal inclusion as a multi-part photographic special effect. The actors and the top half of the cliff face were filmed on the backlot; the lower portion of the cliff is a matte painting; the river is an actual body of water filmed elsewhere, and the falling bad guys have been hand rotoscoped to pass over the matte art and river plate. It all happens quickly but there's a lot of work in this brief shot. |

|

| The original 1933 film THE INVISIBLE MAN was an eye opener at the time and still fascinates students of vintage trick work. John P. Fulton was tasked with realising a number of scenes depicting Claude Rains in various stages of visibility, and for the most part, Fulton succeeded. Fulton explained his methods to American Cinematographer in 1934: "Most of the scenes involved other, normal characters so we photographed these scenes in the normal manner, but without the trace of the invisible man. All of the action had to be carefully timed, as in any sort of double exposure work. The negative was then developed in the normal fashion. Then the special process work began. We used a completely black set (the same set used for the previous takes) - walled and floored with black velvet to be as non-reflective as possible. Our actor was garbed from head to foot in black velvet tights, black gloves and a black headpiece rather like a divers helmet. Over this he wore whatever clothes might be required for the scene. This gave us a picture of the unsupported clothes moving around the entirely black field. From this negative we made a print and a dupe negative, which we intensified to serve as mattes for printing. Then with an ordinary printer we proceeded to make our composite: First we printed the positive of the background with the normal action using the intensified negative matte to mask off the area where our invisible man's clothing was to move. Then we printed again using the positive matte to shield the already printed area, and printing in the moving clothes from our trick negative. This printing operation made our duplicate, compositive negative to be used for printing the final master prints of the picture". |

|

| A great deal of retouching was required throughout the effects footage in order to remove small imperfections and bleed throughs of mattes. As much as 4000 feet of film required retouching with a small brush and opaque dye, with additional hand drawn articulated mattes required in some shots. |

|

| One of the many sequels, THE INVISIBLE AGENT (1942) took the thrill of invisibility to new levels with ingenious scenes of invisible bathing among other gags. Fulton was assisted on the Invisible films by Bill Heckler, John Mescall and Ross Hoffman. |

|

| Also from THE INVISIBLE AGENT is this scene that I've always enjoyed and appreciated. |

|

| For THE INVISIBLE MAN RETURNS (1940) several new twists on the old trick work were utilised, such as this very effective shot where a puff of cigar smoke briefly reveals the previously invisible character. |

|

| Also from THE INVISIBLE MAN RETURNS is this graphic transformation. |

|

| A key frame from the transformation is evidence alone of Fulton's genius. |

|

| This time around it's THE INVISIBLE WOMAN (1941). I discussed this and similar shots from the series with noted visual effects man Bill Taylor and he commented: "The Fulton stuff that really impressed me early on, was in the later Invisible Man/Woman films where only part of the body must be invisible. They had a removable section of the set which allowed the actor actually in the set to play over a black screen just in that area of the body. With this technique everybody is really there at the same time, so eye lines, line timings and so forth are just perfect, while the roto and matte artifacts are limited to just the invisible area, so there's a smaller area to work on and to perfect". Bill also commented: "Fulton was so inventive and such a great craftsman. It's a pity by all accounts he was a real SOB to work with or for. I've never met anybody who had a good word for the guy, and that's just such a shame". |

|

| I was raised on all of those great Irwin Allen tv shows in the 1960's and have fond memories of all of them. Every week we were thrilled and dazzled by out of this world visuals and 'to be continued' plot lines. The frames I've included here are from LAND OF THE GIANTS and, maybe at lower left, THE TIME TUNNEL ( I can't recall?). 20th Century Fox stalwart L.B Abbott handled all of the photographic effects on Irwin's tv shows, and feature films too for that matter, and these shots demonstrate quality and imagination. |

|

| Edward Small's JACK THE GIANT KILLER (1962) - filmed in the amazing 'FantaScope' no less - was an okay adventure in the Sinbad mold. Highly variable effects by a number of suppliers, with visuals running the gamut from just plain bloody awful (the stop motion creature design) through to some pretty amazing optical effects, such as the demonic vision seen here and the remarkable scene shown below... |

|

| JACK THE GIANT KILLER - an entirely groovy piece of optical printing here where the mere swish of a cape produces this lovely young lass. Incredibly well executed, possibly by Howard Anderson. |

|

| Same film, with a fine example of beautifully handled effects animation. |

|

| For the third in the Star Wars series, RETURN OF THE JEDI (1983) the workload of special opticals ILM was faced with was almost double that of the previous film in the series in terms of composites and individual elements. All round, excellent work, with some show stopping visuals such as the speeder bike chase shown here which deservedly earned the film an Academy Award. |

|

| One of the trusted workhorses of Industrial Light & Magic was the 'LS' Printer, so named after it's designer, John Ellis. Optical line up operator David Berry is shown here at work on a shot. |

|

| All of the major studios throughout the 1940's had their own stand alone short subjects units who were kept busy churning out, mostly funny, shorts to accompany the main feature. In fact, even as late as the early 1980's I recall many of these old shorts still in circulation to pad out first release feature films. Shown above is a rare look behind the doors of the optical equipment at the esteemed Jerry Fairbanks unit at Paramount Studios where not only mundane short subjects were produced, but an entire catalogue of quite magical SPEAKING OF ANIMALS comedy shorts. |

|

| The Jerry Fairbanks unit were in a class of their own with this series, where painstaking rotoscoped animation of mouth movements introduced speech and song to an entire range of animals, from chimps and goats to cows and fish. The process was a closely guarded one known as the Duo-Plane Process with head animator/compositor Anna Osborn in charge of making some truly engaging, family friendly entertainment. |

|

| SPEAKING OF ANIMALS, short subject 'Down on the Farm', circa 1942, which I think earned an Academy Award for it's inventiveness. You've got to admire the work when the lip synch is so well match moved (by hand) to frequently moving animals, such as above as the cow sings a charming rendition of 'The Cow Cow Boogie'. |

|

| Anna Osborn and her team of animators and roto artists at Jerry Fairbanks Productions working on one of the SPEAKING OF ANIMALS series. |

|

| "Get along.... get along little doggie, get along......" Just magic! |

|

| Now, as part of the Paramount family, as such, the Fairbanks animators provided some first rate animal action to a couple of Bob Hope-Bing Crosby comedies, with these camel shots from THE ROAD TO MOROCCO (1942) |

|

| Another Fairbanks effects sequence, this one from ROAD TO UTOPIA (1945). |

|

| Seriously under rated, Gerry Anderson's JOURNEY TO THE FAR SIDE OF THE SUN (1969) is a great little film with an involving scenario and terrific Derek Meddings effects work. These shots really work as Meddings' substantial miniatures are flawlessly combined with blue screen actors by optical expert Roy Field. |

|

| Same film, with some great optical composites and model photography. |

|

| An idiosyncratic favourite of mine, the far out KILLER KLOWNS FROM OUTER SPACE (1988) where Mark Sullivan's matte painting has been enhanced with some nice high voltage animation. |

|

| Dino De Laurentiis' KING KONG (1976) was a hit or miss affair on most levels, visual effects included. The mattes and optical photography were carried out at Van der Veer Photo Effects. |

|

| The original KING KONG (1933) still is one of the all time greats in movie history for me. Still impressive effects work abounds, with the above central action sequence being one of the Dunning Process travelling mattes where actors on a limited set have been doubled into a lush jungle setting comprising of models and glass painted scenery. |

|

| Hammer's KISS OF THE VAMPIRE (1963) concluded with this eerie shot of the castle surrounded by hundreds of swarming bats. Les Bowie and Ray Caple were responsible for the matte painted castle and sky, with the bats being 2 dimensional cartoon animation, I believe, done elsewhere and doubled in. |

|

| A sequence in the Errol Flynn film KIM (1950) presents us with an intriguing scene where the location changes mid shot while our main character walks, uninterrupted onward. The shot would entail a slow, soft dissolve from one matte painting to another, followed by a third dissolve into a variation where a vast body of water appears within the landscape. The matte art was supervised by Warren Newcombe, with the character doubled over as an Irving Ries travelling matte. |

|

| KIM matte art and optical component. |

|

| The early eighties saw a number of fantasy orientated adventures, with not all of them being very good. One such was Columbia's KRULL (1983) which was strictly 'ho-hum'. Some interesting effects work here and there, with Derek Meddings looking after the models and such, and Robin Browne taking on optical effects. Future VFX supervisor Peter Chiang animated this transitional scene where a guy transforms into a duck. Chiang still has the original artwork at home apparently. |

|

| There was this nice 'bubbles in flight' effects scene in Jim Henson's LABYRINTH (1986) which I understand was the work of British matte and optical artist, Doug Ferris. |

|

| The completely loopy, 'oh, what were they thinking,' apocalyptic, vampires from outer space saga, LIFEFORCE (1985) may be a complete and utter shambles but it does have non stop special effects work, and all of it top shelf stuff. From Nick Maley's breathtaking animatronic corpses and gruesome gore, through to John Dykstra's super smooth optical effects ... oh, and did I mention Mathilda May? ... this crazy assed flick has it all! Tobe Hooper only ever directed one masterpiece, the original TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE (1974) - and no, as much as I like POLTERGEIST, I reckon Spielberg directed 90% of that one. |

|

| Two of the pioneers in the field of optical printer design and manufacture, Linwood Dunn and, at right, Cecil Love. |

|

| A before and after diagram for an early 'twinning' effect, this being from the Mary Pickford silent film LITTLE LORD FAUNTLEROY (1921) |

|

| An early Cecil B. DeMille picture, MADAM SATAN (1930) |

|

| The final scene from the Warner Bros biopic THE ADVENTURES OF MARK TWAIN (1944) is a visual tour de force. In a long, sustained effects shot Fredrick March is shown in his bed at the point of death, whereby an apparition of him strolls toward a theatrical, heavenly sunrise, all the while the original architecture and features visible within the start of the scene gradually reform into cloud - and all as a continuous photographic effect! Most likely a series of matte paintings cross dissolved very slowly from one to another, with burnt in rising sun element. Hard to describe, but the shot is a winner and earned the film an Oscar nomination in special effects that year, to matte artist Paul Detlefsen and matte cameraman John Crouse - a unique situation whereby a head of department was not named, with the actual technicians rewarded instead. |

|

| THE ADVENTURES OF MARK TWAIN |

|

| I don't have all the details but I've been told that Fox's THE MARK OF ZORRO (1940) was loaded with optical trickery, beyond the normal matte shots that are evident. I'm certain that this seemingly authentic shot of Zorro escaping the pursuers involved some cleverly devised camera effects to give the impression that the horse actually galloped across that narrow little boardwalk. I think there is a possibility that Zorro and horse may have been filmed separately, isolated as a travelling matte element and doubled over the existing footage with maybe a matte painted boardwalk? If anyone knows the deal here, please tell me. |

|

| I've lightened this frame for close inspection. Fred Sersen was a master at this sort of thing... really, a master. |

|

| Another important action sequence from THE MARK OF ZORRO has Tyrone Power escape a band of pursuers by leading his horse up and over the handrail of the bridge and down into the river far below - and all in one shot! Once again, I don't have any details but I'm told by Rocco Gioffre that yes indeed, major optical manipulation was employed on this shot. |

|

| An isolated frame which I've lightened for closer examination. I wouldn't be at all surprised if the entire surrounds, ie rocks, river and riverbank were a miniature, and the bridge supports a matte painting, the bridge roadway a separately filmed element with stunt riders, and with Zorro and horse doubled in later?? Again, I'd love to know. |

|

| One of the all time greats in entertainment, Walt Disney's MARY POPPINS (1964) was an absolute winner in the visual effects stakes, from Peter Ellenshaw's matte art through to Hamilton Luske's intoxicating animation. The frames I've included here detail just some of the film's fantastic effects animation in the unforgettable rooftop dance segment. Lee Dyer was one of the effects animators and a splendid job they did at that. |

|

| More MARY POPPINS magic that features possibly the best effects animation I've seen. Six animators worked full time for a year and a half just to create these firework scenes. |

|

| I was going to include a whole slew of those dropping away to infinity visual effects as I've acquired a great many, but space issues means I'll probably just include this one, even though it is from the diabolically awful MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE (1987). Villain Frank Langella falls into a Matthew Yuricich matte painting. |

|