A warm hello to my regular followers and the ever growing numbers of special effects fans who are still discovering

NZPetes Matte Shot. Today I'll be covering the 1988 George Lucas-Ron Howard picture WILLOW, one of the most spectacular visual effects showcases that emerged during the final phase of the traditional

hand made special effects era - an era where stunning vistas were conjured up by being painted on glass; elaborate in camera multi-plane gags were created through careful planning, pragmatic solutions and a great deal of old fashioned camera knowhow; where dazzling set pieces were assembled element by element, negative by negative on the optical printer in such complex, time consuming and often exhaustive, unforgiving fashion that would most likely leave a modern day CG compositor quaking in his boots. The film was loaded with all manner of magical trick shots - some old and some new - and I'd regard it as among the finest work delivered by Industrial Light & Magic.

The 1980's was an exciting time for many effects fans as we eagerly awaited the next ILM project, or movie that just happened to have that effects house as an a contributor, often with little regard for the film itself. Industrial Light & Magic were at the top of their game throughout the decade with, for this fan at least, an enviable expertise in the fields of matte art, miniatures and cel animated effects in particular, which thrilled me then and still do so now.

|

| Co-Visual Effects Supervisor Phil Tippett |

The 1980's would see a number of similarly themed family pictures such as LABYRINTH, THE DARK CRYSTAL, LucasFilm's own pair of EWOK made for television features to name but a few shows. For my money the 1988 film WILLOW is by far the best of the bunch as far as this genre goes, due in no small part to the fresh helmsmanship of director Ron Howard, the most agreeable Warwick Davis as our title character and above all else a wonderful 'English sensitivity' in the overall flavour and texture of the narrative - an important factor that can only be a strong positive factor in such fantasy storytelling.

WILLOW was a large budget fantasy tale that producer George Lucas had been wanting to put into production for some years. The story of a band of merry little adventurers in a mythical land who are tasked with arranging the safe passage of a special infant in order to put a stop to the sneering wickedness of the thoroughly vile Queen Bavmorda, and told in a very

Tolkien-esque fashion. Filming took place on diverse locations such as here in New Zealand, Wales and at Elstree Studios outside of London, as well as some pick up shots made during post production in California.

The mammoth trick shot roster on WILLOW where over 350 visual effects were required would necessitate no fewer than three overall Visual Effects Supervisors: Dennis Muren, Phil Tippett and Michael McAlister, with ILM veteran Christopher Evans as Matte Painting Supervisor. Each were tasked with overseeing their own effects sequences which were divided up among the supervisors into specialised fields such as Tippett supervised the stop/go motion creature sequences, Muren taking on the ethereal fairy sequences and groundbreaking transformation shots, and McAlister having the substantial load of some 170 so called 'Brownie' shots - photographing and compositing eight inch tall elf like forest folk into life size settings and action sequences via blue screen travelling matte photography and complicated pin block techniques to allow maximum freedom in compositing.

I tend to deal mostly with matte artistry in this blog as my regular readers will know, but on occasion I branch out to include other visual effects techniques when I find it important enough and relevant. WILLOW is one such motion picture and as such I'll begin with a detailed look at the mattes, followed below by many examples and explanations of the optical, cel animation and go-motion effects techniques employed on the film. Ya' can't say you ever get short changed by NZPete!

WILLOW would receive an Oscar nomination for Best Special Visual Effects in 1988 along side the dynamite Bruce Willis actioner DIE HARD and the largely animated WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT, with the

bunny cartoon-noir snapping up the FX Oscar unfortunately as I feel WILLOW really deserved it

(and don't even get me started on BLADERUNNER losing out to that bug-eyed E.T in the effects category a few years earlier... is there no justice in the world?) , but I guess ROGER RABBIT was a bigger hit and ain't that how it works? I mentioned this to Matte Supervisor Christopher Evans and he too felt somewhat disappointed at the outcome that year.

So, without further ado, let's take a pleasant journey to a land far, far away, of little people, even littler forest folk, rather fetching fairies and their drop dead gorgeous fairy queen, a wicked old hag with a pandora's box bursting with nastiness and a two headed dragon ........... oh, and some nice New Zealand scenery.

Enjoy

NZPete

..........................................................................

*In preparing this retrospective I am most grateful to former ILM Supervising Matte Artist Chris Evans for his reminiscences, technical explanations and photographic material pertaining to WILLOW's many wonderful matte shots.

..........................................................................

|

| WILLOW is a warm, charming and beautifully photographed (by Adrian Biddle) fantasy adventure with a winning star turn by Warwick Davis as the title character. Support from Val Kilmer isn't bad, though Kilmer had yet to find his feet with his astonishingly brilliant performance as Jim Morrison in Oliver Stone's THE DOORS a few years later, though as usual I digress. A pleasant family film though not one entirely devoid of quite hideous beasts, a worryingly unbalanced and patently evil Queen, and an irritating pair of comic sidekick diminutive Brownies whose schtick quickly outstays it's welcome. |

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

THE MATTE PAINTINGS:

CHRISTOPHER EVANS on WILLOW:

|

| ILM Supervising Matte Artist Christopher Evans |

As Chief Matte Artist on WILLOW my job was to provide Director Ron Howard with a series of matte shots establishing the look of the make-believe world in which the action takes place.

To create the thirty shots I worked closely with Director of Matte Photography Craig Barron, Optical Supervisor John Ellis, some four Matte Artists - Caroleen Green, Michael Pangrazio, Sean Joyce and Paul Swendsen - in addition to model makers, animators, effects editors and the production staff at Industrial Light and Magic. We began designing shots in September 1987 and delivered finals in April 1988.

|

| Ron Howard, George Lucas, Craig Barron & Chris Evans discuss matte concepts |

The primary challenge with a fantasy film like WILLOW is to design matte shots that fulfil the Director's imaginative vision of the picture with unusual and breathtaking scenes which do not, however, call attention to themselves as paintings. The shots needed to match locations in New Zealand and Wales, and enhance the scope of the live action as filmed on sets at Elstree Studios in the United Kingdom. A sense of mood and epic scale was provided at key points, as in the montage of Willow's journey through enchanted lands and his arrival at the ominous castle of the evil Queen Barmorda. Such full screen, daytime panoramas are very difficult to paint convincingly and demanded the utmost artistic skill from myself and the other artists.

Various traditional and innovative photographic techniques were used including latent image and optical compositing. Wherever possible, camera movement was introduced. To create the boom shot of the canyon maze, the live action area was rear projected into a low-relief painting surrounded by a multiplane miniature set and photographed with a motion control camera system.

A new technique pioneered at the ILM Matte Department was the double-exposing of a matte painting over an exposure of a miniature set, so that the two images are blended together at the artist's discretion. Combining the details and textures of a miniature with the perspective and atmospheric lighting of a painting would bring a new dimension of realism to the matte shot - as in the scenes of the Queen's castle - and I believe set a new standard for the effects industry in this area.

By creating convincing illusions of a fantastic, yet believable world of make-believe, I know the matte paintings contributed greatly to the look and feel of WILLOW. Ultimately, the success of these shots was the result of the dedication and artistic and technical excellence shared by the team who had worked closely together producing matte painting effects on over twenty-one motion pictures. It was a privilege to lead this group in creating these matte shots for WILLOW.

Christopher Evans

September 2017

|

| The first of some 27 matte paintings that would expand the vision of the film's Director, Ron Howard of the mythical Kingdom. Unusually, the ILM matte department were not involved in the pre-production stages, nor the on location matte plate photography. During principal photography an inordinate number of potential matte shot plates were photographed on the various locations in New Zealand, Wales and England with the notion of these plates being insurance later for possible matte painted enhancements though ultimately very few of these 'potential plates' ended up being used, as no definite design nor look of the matte additions had yet been decided upon. About 20% of the mattes originated from plates that had been shot in New Zealand or the UK. Matte Supervisor Christopher Evans can't recall who painted the above shot but told me that it's a very nice matte. According to Chris, his department only really got involved once George Lucas called him, fellow matte artist Mike Pangrazio and matte cameraman Craig Barron out to the Skywalker Ranch to view a rough assembly of the mostly complete picture. Chris says "George would stop the film from time to time and say that a matte shot of a castle was needed here or we want a landscape there. At that time he gave us his shopping list of around 30 matte shots." |

|

| Chris Evans told me that this shot was one of matte cameraman Craig Barron's "brilliant concepts". A latent image sunrise, filmed undercranked to slightly speed up the movement of the clouds across the sky, with a large 4x8 foot sheet of Masonite carefully cut out to resemble mountainous contours set up between the camera position and the actual sunrise. This latent negative was then taken back to ILM where matte painter Paul Swendsen added subtle detail to the silhouette that was already masked on the film. Mist and birds were added in a second pass, with the six actors, having been photographed separately at Skywalker Ranch in silhouette at magic hour bi-packed to hold out the mist exposure. These were two very old tricks, latent image and bi-pack used together and were commonly used back in the heyday of cinema by vintage practitioners such as Clarence Slifer, Jack Cosgrove, John P. Fulton and Fred Sersen on scores of motion pictures. |

|

| One of the dozens of conceptual painted sketches made by Chris Evans, with this being the overall look for the scene with the Nelwyns leaving their village. |

|

| Christopher Evans at work on one of several paintings he personally completed for the film. The plate is original negative or latent plate shot in Marin County, California with the matte taking up approximately half of the screen. |

|

| The finished shot combined on original negative. George Lucas requested Chris to paint landscapes based on the area around Qui Lin in China with many unusual limestone rock formations. |

|

| Sean Joyce matte shot combined in front projection, with painted giant trees behind the actors and a miniature tree trunk in the foreground. |

|

| On location at Birney Falls in Northern California (or Oregon?) with Chris Evans shown etching the proposed matte line onto glass mounted in front of the VistaVision matte camera for a spectacular latent image matte shot (shown below). Also shown here are Assistant Matte Cameraman Wade Childress and Director of Matte Photography Craig Barron. Chris: "George and Ron Howard allowed me to be Second Unit Director for these shots and to be in charge of the actors and crew on location. They were great fun to be with." |

|

| Conceptual painting by Evans for the Birney Falls scene. |

|

| The tiny trekkers cross a spectacular landscape with those Chinese mountains that Lucas loved so much. Once Craig Barron had composited the Chris Evans painting into the latent image VistaVision, the ILM Optical Department added a tilt down from the mountains to the cast. John Ellis was Optical Supervisor, with John Alexander provided the motorised tilt on the optical printer. A most beautiful shot results. |

|

| Another matte concept piece by Evans for the sequence where the characters traverse a dangerous gorge via fallen log. Hmmm, I wonder if there was ever a 'deleted' spider pit sequence here? |

|

| Stages of the gorge matte shot with extensive painting, very limited live action (the actors only) and what appears to be some sort of miniature foreground foliage added as a separate element? |

|

| Matte Supervisor Chris Evans directs as Cameraman Craig Barron photographs the diminutive cast atop a parked truck against a pale, overcast sky. Chris: "For the scene of the Nelwyns trekking across a log bridge over a deep chasm filled with ferns Craig had the bright idea of a bi-pack run in-camera of the actors in silhouette. They were filmed on the edge of this truck over foam pads for safety to avoid safety problems." |

|

| A closer look at the matte art. |

|

| The final scene. |

|

| Matte concept painting by Chris Evans with technical details for the camera operator. |

|

| ILM's Paul Huston was (and possibly still is?) one of the original staffers, with a career spanning back to the very first ILM project, that little 'Space Film' STAR WARS in 1977. Considered by many to be the maestro of miniatures, Chris Evans too had the highest of praise for Paul and his contributions to WILLOW, among many other assignments. With this shot a miniature castle will be combined with matte painted architectural extensions as well as live action, a painted landscape and sky and other elements. |

|

| Stages for reaching the final composite. I'm pretty sure that the distant landscape and volcanos are actual location plates shot here at Mt Tongariro in New Zealand. |

|

| The final glorious composite. A foreground tabletop miniature and lower walls of the castle by Paul Huston, whom Chris refers to as "a master model maker". All latent image, with added painted in upper castle and dramatic sky. Double exposure of steam. Chris told me: "This is one of the best skies I ever did in oil." |

|

| An invisible trick shot where a beautifully painted moonlit snowscape and encampment has been given that added touch of realism by including a miniature tent in the foreground. In painting the scene, artist Michael Pangrazio, having detailed the majority of the full painting, left the foreground tent as only a silhouette in order that model specialist Paul Huston could construct a miniature tent with it's own illumination inside as flickering lanterns, with the final shot photographed onto latent image. When I quizzed Chris Evans about this wonderful shot he said: "This is definitely a Pangrazio masterpiece! No one is like Mike with moonlight and snow and such strong composition." |

|

| A quick 'blink and you'd miss it' matte enhancement where the sky and sun flare have been painted in. |

|

| Matte painted canyon walls in a shot that occurs just prior to the big WILLOW money shot, as illustrated below... |

|

| Effects wise, I regard the big 'boom shot' in the middle of the movie to be the highpoint. The point was to start in on the riders on horseback and pull out up and over a vast maze of sheer canyon walls and peaks. Evans decided early on that straight matte art would not suffice as the 'flat' aspect of the art, no matter how well rendered it might be, just wouldn't exhibit the proper parallax shifts as one would seen in real life. The answer was to combine a large 18x25 foot multi plane miniature set with a process projected live action plate and to somehow invisibly combine the blend between the two. In this rare out take from Chris we can see the dark portion below where behind glass a rear screen projection system has been set up. |

|

| A closer look shows Assistant Matte Cameraman Wade Childress adjusting the process projector. |

|

| In this photo, model maker Paul Huston works on detail. The actual process screen will ultimately be flawlessly blended through painstaking painting to conform with the live action plate in terms to tone, hue and contrast. |

|

| Paul Huston applies texture to the canyon walls while Christopher Evans carefully paints the blend around the process screen. Evans also painted the sky backing. |

|

| ILM's AutoMatte camera system with vast canyon miniature beyond. |

|

| The start position of the pullback revealing the riders lost in the vast canyon maze. Although miniature rear projection has been around for several decades and was used on films as notable as the original KING KONG in 1933, this may be have been the first time the technique had been used in such a complex manner with repeatable camera moves. The plate was rear projected onto a sheet of glass embedded in the miniature rock section. The painting of the edges of the glass screen was blended to match the 2D glass and this glass then blended perfectly into the 3D form of the miniature. When the camera pulled back and craned up to reveal the full miniature canyon, it had natural 3D parallax and perspective which would not have been possible on just a 2 dimensional painting. Craig Barron photographed the live action plate, with Craig's assistant Wade Childress programming the AutoMatte and handled the compositing. |

|

| As tricky as the shot was, at a late stage George Lucas asked the team to add a crow flying through the canyon. Kim Marks photographed a crow against a white sky which was then bi-packed into the shot as the AutoMatte move was photographed. |

|

| The riders exit frame right while we the audience are still trying to find that blend! |

|

| The kindly folk approach Kir Asleen Castle. A tilt up shot of a Sean Joyce matte painting, though one that apparently was most problematic according to Chris Evans: "This was a very hard shot ... I remember having to take over a shot like this that just wasn't looking real. We just kept on plugging away at it. One day in the screening room I said to George, "this is a really hard shot!", and he just said "Good luck."" |

|

| Detail |

|

| ILM matte artist Sean Joyce at work on the problematic shot. |

|

| One of the best mattes in WILLOW was this stunningly illuminated Throne Room which was entirely painted except for the small strip of 'runway' and the throne. The original live action plate shot in England was flawed and unusable so a small second unit directed by matte artist Sean Joyce and populated with photo doubles was shot at ILM. |

|

| As I happen to just love this painting I asked Chris what he remembers about it: "Sean was definitely involved with and designed the Throne Room shot, and I remember him directing the live action. He may have begun the painting too - I'm not sure how much Sean did - but Caroleen Green completed it. Craig conceived of the backlit windows idea scraped out of the glass painting and shot with diffusion filters...It really makes it." |

|

| At left is the modest live action mock up at ILM where artist Sean Joyce has his turn at directing some stand ins for what will be a brief establishing shot. At right is the masked off plate prior to compositing. |

|

| A rare test composite, not properly balanced nor cropped to cut in with the 2.35:1 Scope production footage. Note the top edge of the matte art and the as yet non backlit window slits. The shot will also have a slight tilt. |

|

| Detail from Caroleen's magnificent matte art. |

|

| The final shot. |

|

| Matte Painter Caroleen Green at work on the mighty Throne Room shot. |

|

| Chris had a somewhat amusing memory of making this shot work: "This is a miniature castle and foreground. Live action plate of a boy riding in on a horse, with the setting sun a light source double exposed. The lens flare was tricky so Dennis Muren suggested 'nose grease'. I thought he was kidding, but according to his instructions I touched my the tip of my nose and smeared a bit of 'nose grease' on a sheet of glass in front of the lens ands wiped it around until the sun flare was just right. Sort of a 'spit and polish' solution and definitely hands on and very physical in a bizarre sort of way." |

|

| For this closer view we have a live action foreground plate, a miniature castle with painted extension and DX'd steam. A Michael Pangrazio matte as best Chris can recall. |

|

| Live action plate shot in Wales with a partially constructed castle facade matted to a combined miniature/painted element. |

|

| The somewhat imposing castle of the equally imposing Queen Bavmorda is seen here in a dramatic reveal by way of a tilt up on a large and detailed Caroleen Green matte painting. |

|

| Close look at some of Caroleen's detailed stonework. |

|

| Caroleen Green |

|

| Another of Chris' conceptual paintings for a proposed matte shot. |

|

| A shot I also admire greatly: "This was based on a Mike Pangrazio trick from INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM. For this shot we used a real sky latent image shot with silhouette of towers and distant horizon. The real sky carries the reality and the artist simply fills in the shadow detail with an additional exposure. Caroleen worked on this one I believe." |

|

| Another invisible trick that slipped past most audiences was this one. A combined miniature/painting/live action composite. Paul Huston constructed a miniature stone wall from styrofoam in forced perspective, around three feet tall and two feet wide. As an added bonus Huston also contributed a tiny skeleton in a cage suspended over the stairwell and added a flickering orange light from an unseen flaming torch. Matte painting extended the miniature set and blended it into the live action set. |

|

| Many of the WILLOW matte shots feature camera moves - some subtle and some jarring - with this quick tilt up falling into the latter category. Paul Swendsen painted this substantial matte, though Chris mentioned to me that they had perspective problems that needed sorting out. An additional rain element was overlaid by shooting sprinklers in front of a black velvet drape on a stage with the falling water droplets strongly backlit in order to make them show up better. Cel animation for the lightning strike was also introduced at a later stage. |

|

| Close up detail from Swendsen's matte art. |

|

| Paul's original matte painting clearly shows just how small the live action element would be. |

|

| Paul Swendsen hard at work. Apparently Paul left the project early. |

|

| This majestic shot was Michael Pangrazio's big tilt up matte. Aside from a gateway and a small stone wall, it's practically all painted excepting a small miniature set of the two turrets in the middle with the red banners blowing in the breeze which was a separately photographed element shot on the stage at ILM. The live action plate below with cheering crowds was in the first instance a latent image or rear projected plate though when George decided that a bigger crowd was required an additional large group of extras was blue screened in. The shot was very difficult to pull off as so many elements were integrated and the optical printer operator was tilting up. |

|

| An out take from the Matte Department which shows Pangrazio's wonderful painting without the live action plates yet added though it does have a temporary composite of the miniature turrets with red banners, though these have not been corrected yet to match the hue of the painting. |

|

| Master matte painter Michael Pangrazio with his preliminary block in of the Kir Asleen castle. |

|

| Detail of Kir Asleen matte art. |

|

| An early unused concept painting for the Nelwyn village shot that concludes the film. |

|

| A later concept painting by Chris Evans that will form the basis for the sprawling vista at the films' end. |

|

| A mock up by Chris for the final look of the proposed shot. This is a rough painted sketch over the top of a small photograph of the live action plate. Sadly, the second big ILM coffee table book 'Into The Digital Realm' had this described as being the finished matte composite, when in fact it is anything but. Whoops! |

|

| At left is the live action plate for the closing shot, photographed by Craig Barron in an empty field behind ILM. Just a few extras, some animals and mock up dwellings. At right Christopher Evans paints the sprawling vista. |

|

| Chris told me how the shot came together in a recent conversation: "My big pull back shot of Nelwyn Village which extends right into the end credits had a rear projection plate in the middle of the village (filmed out back behind the ILM complex) and another process plate for the flowing river (shot by Scott Farrar in Northern California). The background landscape was a large oil painting measuring 4x8 feet. The side hills and forest were photo blow ups on flat layers. As the camera pulled back and craned up, everything had 3D perspective. This anticipates the Digital 3D matte shots of today where all the areas of the scene are put on 'cards' to provide perspective shift as the camera moves. Using the AutoMatte we could program what was close to being a real 3D matte shot, not just a move on a big painting." |

|

| "The shot was composited in several passes on the AutoMatte, programmed to repeat the move on any number of elements, with Craig and Wade Childress doing the camerawork. One day near the end of the production we were screening this shot for George. The shot was on screen for about two minutes as the credits hadn't been superimposed over it yet. It just so happened that a film crew just back from China was in the screening room that morning and, after watching the shot they asked George how on earth he was able to get permission to clear away so much forest in the Qui Lin area of China to film? George's reply was that we didn't even go to China, and that everything they had just seen was a visual effects matte shot." |

|

| In an earlier interview Chris said: "It's the most challenging shot I've ever had ... the challenge was to have a clarity in the atmosphere to enable one to see into the distance, yet maintain the soft, silvery light quality of the village in England where they worked. He also wanted to have the quality of light that is found in the Hudson River School of painting, so I chose the silvery grey light of Frederick Kinsett rather than the orange, golden light of, say, Albert Bierstadt." The matte would remain on screen for some fifty seconds until fade to black - an unusually long time for a trick shot where 2 to 4 seconds would be the norm when it comes to painted mattes. |

|

| The matte art. |

|

| Close up detail of Evans' matte art. Two live action plates will be projected in as well as photo cutouts of dense forest added in the near foreground. |

OPTICALS, FAIRIES AND BROWNIES:

|

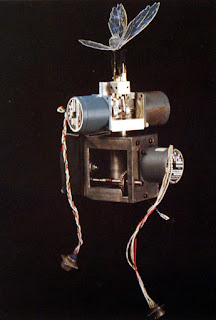

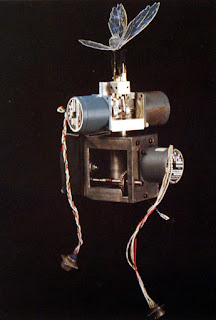

| WILLOW featured a staggering 250 optical composites and almost 1000 cel animated elements to flesh out the broad fantasy theme in style. I personally found the fairy sequences, made under Dennis Muren's supervision, the most charming and proved to be just what I had expected the ILM artisans would produce. The rather cute little 4 inch fairies were gymnasts hanging from overhead wires and 'pin blocked' which involves re-photographing the already filmed images under an animation stand whereby precise re-positioning of the characters frame by frame, animated wings etc can be added to characters while in movement. The fairies wings were developed from special membranes controlled by a mechanical device (shown below). Bruce Walters was charged with creating the necessary motion control sequences to maintain exact alignment of the wing elements to the already photographed performers. Peter Daulton pin-blocked each fairy to their individual wing elements. Additional elements such as fairy dust and motion streaks were also created by the team. |

|

| Visual Effects Supervisor Dennis Muren (centre) directs the action with George Lucas seen standing at the back. |

|

| WILLOW's Animation Supervisor, Wes Takahashi at work creating scale fairy wings out of clear plastic carefully etched and shaped. |

|

| John Knoll's one of a kind 'wing flapping machine' with Wes Takahashi's plastic fairy wings fixed in position. You probably won't find these in Wal-Mart boys and girls though I do believe Wile E. Coyote had an Acme one in an old Chuck Jones ROADRUNNER cartoon? |

|

| The fairies in full flight with a gorgeous ethereal glow and wings-a-flapping, complete with motion blur. |

|

| For the scenes with Cherlindrea, The Fairy Queen, Dennis Muren was tasked with photographing the actress with a high-speed camera under strong back light and at 4 stops over-exposed to achieve the desired glow, with this footage then optically combined into a miniature forest set. |

|

| Age old techniques utilising ripple glass manipulation to create a deliberate distortion were applied to the scenes of Cherlindrea interacting with Willow and companions. |

|

| To enable the desired interactive lighting within the forest setting for when Willow meets Cherlindrea, veteran ILM model specialist Lorne Peterson - another of the old guard who's been with the company since it's inception - constructed the one-third scale miniature Redwood forest. |

|

| Michael McAlister was the Visual Effects Supervisor upon who's shoulders the considerable responsibility of designing, photographing, and compositing the large number of 'Brownie' sequences. Brownies are eight inch tall elf like fellows who's purpose it seems is solely to provide comedy relief, though the two key Brownies rather quickly become tiresome and if it weren't for all of the superb optical compositing that pulled these shots together I feel things could have been better served with fewer Brownie antics. However, the work that went into scenes such as this one above was pretty staggering, with not only multiple Brownies all seen in action at once, but many of them are firing arrows too, with the arrows themselves not being present at all during the blue screen shoot for safety reasons. ILM's animation department under Wes Takahashi constructed tiny model arrows which were in turn match moved and dropped into the shot optically. Each actor simply mimed drawing his arrow from his quiver and pretended to fire, with the visual effects boys providing the 'action'. The sort of elaborate trick that I still find so impressive. |

|

| For my money this is the most impressive of the Brownie optical composites in the show, and one of the best overall photographic effects on offer in WILLOW. Young Warwick Davis picks up a Brownie and pops him, kicking and struggling, into a leather pouch. Extremely good match moving here with the pin block technique, and a trick which has been attempted numerous times over the years with the conventional photo-chemical methods, though I must remind readers that the legendary John P. Fulton had already done this same gag with multiple tiny people in Universal's THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN as far back as 1935 with astounding success in a sequence that still boggles the mind. |

|

| Technically, these Brownie shots are excellent. Not just the bog standard blue screen travelling matte insertion of 'small people' but these are incredibly well designed and photographed visuals, with terrific optical cinematography and bold camera moves with our characters able to interact all over moving objects and so forth through precision pin block techniques and rotoscope animation. |

|

| More match move travelling matte work. |

|

| The technical requirements of the Brownie's scenes varied from shot to shot. Extensive calculations were required for shots ranging from Brownie's falling off a moving wagon, nearly being flattened by stampeding horses and running up and over objects and people. Each time a Brownie runs, jumps or falls, the effects of gravity, as well as height, distance and speed all needed to be scaled down from a normal sized actor to that of an imaginary eight inch tall film character. In almost all cases the Brownie actors were filmed at 22 fps to aid in the miniaturisation of their movements. An inclined treadmill (shown above) was used often to allow the actors to run in place against the blue screen at angles that would match up with the setting or terrain they were going to be ultimately matted into. Extensive application of the pin block alignment technique during re-photography under the animation stand permitted the optical effects cameramen to exactly reposition the characters frame by frame to compensate for movement in the background plate. |

|

| Another most impressive optical jigsaw with scores of tiny Brownies roping up and dragging our hero and sidekick away into the enchanted forest, with one of the Brownies walking around on top of Warwick Davis as they are dragged away, with the entire thing so well choreographed and executed. |

CEL ANIMATED EFFECTS:

|

| I've always been a sucker for talking animal trick photography, with many old time forays into that realm still proving a delight such as the old Jerry Fairbanks Unit based at Paramount in the 1940's where through their 'Duo-Plane Process' hand animated mouths were realistically matted into motion footage of every kind of animal you can imagine in the Oscar winning Speaking of Animals series, with cows singing ballads, chimps telling jokes and so on. Fantastic stuff folks! There happens to be a few sequences in WILLOW where animals not only speak, but have perfect lip sync to boot! ILM farmed this assignment out to one of the industry's best specialist animation houses, Available Light, run by John Van Vliet and Katherine Kean. Apparently early trials with mechanical animals with moving mouths was tried out on location but soon abandoned. Plan B was to shoot background plates with the real animals and through highly detailed hand drawn animation of just the lips and mouth - all animated on an Oxberry to precisely match a pre-recorded dialogue track where lip sync was important. Every cel was hand inked and hand painted, with the cels being shot using the frontlight-backlight matting system, with some additional rotoscoping required for certain shots. Available Light spent some five months on the project, turning out 35 talking animal shots. |

|

| From this reasonably good frame blow up from the BluRay print one can see the detail put into the drawing and hand colouring of the jaw, teeth and lip of the (real) possum. Available Light's animators on these shots included John Van Vliet, Mike Lessa, Kathleen Quaife-Hodge and Daryl Rooney, with Joseph Thomas manning the Oxberry animation stand. |

|

| Each frame was projected down onto photographic print paper, blown up to an easily workable size as it was only the mouth that needed animation enhancement, with some 2000 photo-roto prints made, with the most difficult aspect being just how would an animal enunciate the English language believably? Each frame of preliminary animation on the photo prints was then meticulously transferred by hand onto transparent cels using special ink and paint in readiness for photography and compositing. |

|

| Queen Bavmorda's arm begins to turn to stone in this brief shot, with some nicely effective cel animation and roto work by Gordon Baker to an almost gruesome effect. |

|

| Yes friends, NZPete loves good effects animation almost as much as he does great matte shots. Industrial Light and Magic were renowned for their jaw dropping cel animated effects shots in countless shows, with WILLOW being no exception. For the sequence where the wicked and thoroughly disagreeable Queen Bavmorda meets her maker (oh, sorry... spoiler alert) much top of the line fx animation and some funky never before seen practical smoke elements are employed. |

|

| Visual Effects Art Director Dave Carson designed the sequence and in particular the look of the mysterious red smoke that envelopes and causes grief to the evil Queen. |

|

| And what a knock out of a sequence it is at that! The electricity bolt is a cel animation element by John Armstrong and Sean Turner but the weird red smoke was, I believe, largely a practical effect physically created on a stage as a separate element and shot via some sort of slit-streak photography which I imagine was long exposure with some sort of camera move while the shutter's open as with the Trumbull Slit-Scan method used on 2001(?). Your humble author has never really fully grasped this effect and I'd love to see an actual breakdown of the trick to figure it out, much as I would give my left kidney to know how John P. Fulton and Roswell Hoffman managed to pull off that grand daddy of all 'smoky dematerialisation' opticals in Universal's SON OF DRACULA back in the mid forties. That's some damn fine dematerialisation if ever there was one! |

|

| Some terrific - and no doubt terrifying to kiddies back in the day - skeletal animation flashes achieved by Tim Bergland. |

|

| Great stuff, though borrowed I suspect from the aforementioned Universal picture SON OF DRACULA. |

STOP & GO-MOTION ANIMATION:

|

| A brief stop motion sequence by veteran independent animator David Allen occurs during the final stages of the picture, with a bewitched brazier magically coming to life, and in true Harryhausen fashion a battle ensues. At left are Lucas, Director Ron Howard, FX Supervisors Phil Tippett and Dennis Muren. Right picture shows David Allen animating said brazier which will be integrated via blue screen into the live action. |

|

| The scene as it looks on screen with Willow, who, as the late, great Peter Finch once said in the Sidney Lumet masterpiece NETWORK, "is as mad as hell and he ain't gonna take it anymore"; as Willow proceeds to kick some brazier ass. Strongly resembles the skeleton fight in the wonderful 7th VOYAGE OF SINBAD in tone and style. |

|

| There are a couple of brief, though excellent mechanically puppeteered transformation scenes in the movie too, though these last just a few frames and are ultimately usurped with early computer graphics to complete the trick. These images are just part of the complex sequence where goat transforms into an ostrich, then into a turtle, a tiger and finally a woman! Dennis Muren would oversee these sequences in conjunction with the ILM creature shop and the fledgling computer graphics department. |

|

| Some behind the scenes views of the work in progress. |

|

| David Allen acted as coordinator to the creature effects team in making these shots possible, with compressed air, vacuum, cables and rods all ably employed by the puppeteers in the grand old style many of us remember with fondness as a viable in-camera physical effect in many classics such as my faves John Landis' fabulous AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON, John Carpenter's THE THING and that 'what the hell were they thinking' Tobe Hooper movie LIFEFORCE (hardly a classic this one, but magnificent fx work in an utterly silly flick!). The modern CG really isn't in the same league folks! |

|

| It's really outside of the intent (and interest) of this blog, but I'll include a few frames of the CG as it is part of what began as a physical effects sequence. |

|

| I believe it was the first application of what became known as 'morphing' CG technology - an effect that, while fascinating to audiences at first, quickly became passe and was far too over used in a million tv commercials and music videos. For this groundbreaking metamorphosis, ILM had software written that could allow the isolated image to be digitally stretched, squashed and shaped into the shape or outline of another isolated image. |

|

| A highly evocative conceptual painting for the big effects laden finale with the two headed Eborsisk and a legion of guardsmen in Queen Bavmorda's lair. |

|

| The climactic set pieces of WILLOW entailed a fire breathing two headed creature and a very H.R Giger-esque inspired 'thing' that erupts from what appears to be a bloody placenta, or a big lump of five day old spaghetti, take your pick. Chestburster me thinks.... John Hurt take cover! |

|

| Three foot long scale models of the beast were built at ILM complete with breathing bladders and a fully articulated posable armature skeleton to enable both stop motion and go motion animation. |

|

| The talented Phil Tippett is shown here animating the Eborsisk. Tippett did much splendid work over the pre-digital years, with ROBOCOP 1 and 2 and THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK being absolute high points. Some of these WILLOW shots also featured small stop motion people amid the action. |

|

| The VistaVision camera records a go motion shot. As WILLOW was a Scope film and certain Eborsisk scenes needed to be shot as rear projection, the optics of anamorphic lenses are notoriously difficult to work with for effects shots due to focal issues and the relative slowness of the lenses, animators Harry Walton and Tom St. Amand were having to work with exposures as long as three minutes per frame, which I'm sure must have been somewhat disconcerting to say the least as the exacting hands on nature of stop motion animation requires a clear focus on the part of the animator as to just where the puppet is going in small incremental movements and one can imagine how the slightest diversion could lead to problems. |

|

| The model creature was attached to steel rods and driven by concealed motion controlled stepper motors during frame by frame exposure thus allowing a natural motion blur to occur on while the shutter is open for each frame of movement as opposed to the rapid succession of entirely static frames which have generally been the basis of stop motion work. ILM pioneered the go-motion process for the earlier film DRAGONSLAYER in 1982 though I believe some earlier rudimentary 'motion blur' gags may have been devised by Jim Danforth and Randall William Cook on some other films. |

|

| Animator, effects cameraman, matte artist and all round visual effects expert Harry Walton carries out traditional stop motion for a subtle close up shot whereas the go motion process tended to be used more for the major puppet moves. |

|

| Every shot with the Eborsisk involved multiple elements such as matte art, smoke and fire elements, animated arrows and more. Much of the interaction between the puppet and the actors required blue screen travelling matte work and on some occasions rear screen process projection to combine the puppet with the live action. Extensive hands on rotoscoping was also required in a number of instances |

The mammoth trick shot roster on WILLOW where over 350 visual effects were required would necessitate no fewer than three overall Visual Effects Supervisors: Dennis Muren, Phil Tippett and Michael McAlister, with ILM veteran Christopher Evans as Matte Painting Supervisor. Each were tasked with overseeing their own effects sequences which were divided up among the supervisors into specialised fields such as Tippett supervised the stop/go motion creature sequences, Muren taking on the ethereal fairy sequences and groundbreaking transformation shots, and McAlister having the substantial load of some 170 so called 'Brownie' shots - photographing and compositing eight inch tall elf like forest folk into life size settings and action sequences via blue screen travelling matte photography and complicated pin block techniques to allow maximum freedom in compositing.

The mammoth trick shot roster on WILLOW where over 350 visual effects were required would necessitate no fewer than three overall Visual Effects Supervisors: Dennis Muren, Phil Tippett and Michael McAlister, with ILM veteran Christopher Evans as Matte Painting Supervisor. Each were tasked with overseeing their own effects sequences which were divided up among the supervisors into specialised fields such as Tippett supervised the stop/go motion creature sequences, Muren taking on the ethereal fairy sequences and groundbreaking transformation shots, and McAlister having the substantial load of some 170 so called 'Brownie' shots - photographing and compositing eight inch tall elf like forest folk into life size settings and action sequences via blue screen travelling matte photography and complicated pin block techniques to allow maximum freedom in compositing. WILLOW would receive an Oscar nomination for Best Special Visual Effects in 1988 along side the dynamite Bruce Willis actioner DIE HARD and the largely animated WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT, with the bunny cartoon-noir snapping up the FX Oscar unfortunately as I feel WILLOW really deserved it (and don't even get me started on BLADERUNNER losing out to that bug-eyed E.T in the effects category a few years earlier... is there no justice in the world?) , but I guess ROGER RABBIT was a bigger hit and ain't that how it works? I mentioned this to Matte Supervisor Christopher Evans and he too felt somewhat disappointed at the outcome that year.

WILLOW would receive an Oscar nomination for Best Special Visual Effects in 1988 along side the dynamite Bruce Willis actioner DIE HARD and the largely animated WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT, with the bunny cartoon-noir snapping up the FX Oscar unfortunately as I feel WILLOW really deserved it (and don't even get me started on BLADERUNNER losing out to that bug-eyed E.T in the effects category a few years earlier... is there no justice in the world?) , but I guess ROGER RABBIT was a bigger hit and ain't that how it works? I mentioned this to Matte Supervisor Christopher Evans and he too felt somewhat disappointed at the outcome that year.